(Alex Haley On Writing is from Alex Haley’s commencement speech he delivered to an audience in Alumnae Hall at Brown University on May 26, 1984, which was published in the June / July 1984, Volume 84, No. 9 issue of Brown Alumni Monthly.)

(Alex Haley On Writing is from Alex Haley’s commencement speech he delivered to an audience in Alumnae Hall at Brown University on May 26, 1984, which was published in the June / July 1984, Volume 84, No. 9 issue of Brown Alumni Monthly.)

Brown’s 216th Commencement was held on Memorial Day, Saturday, May 26, 1984, earlier than in previous years, thanks to the University’s new academic calendar.

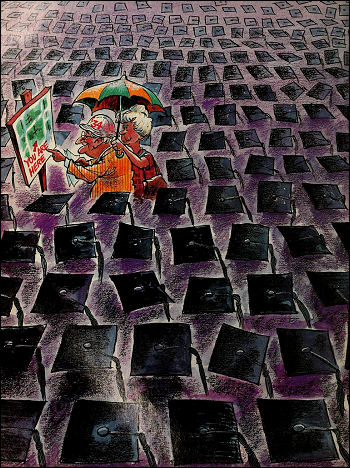

Some 1,500 seniors and several thousand alumni gathered under a gray (and ultimately drizzly) sky to enact the traditional pageantry of the parade down the Hill, to listen to orations in the Meeting House and ceremonial addresses on the Green, to be photographed by families, to say hello, and to hug good-bye.

For seniors, it is a day when windows open onto a new time in their lives.

Alex Haley’s best-selling novel, Roots, based on his family’s history, was made into the most-watched television program of all time. Earlier Haley pioneered the “Playboy Interview” format for Playboy magazine, and was co-author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Alex Haley was at Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island) for the graduation of his niece, Anne Palmer Haley—the daughter of his brother George Haley. Haley spoke at a Commencement Forum to an audience of some 600 in Alumnae Hall where he spun tales of growing up in the South and the flowering of his novel Roots. A portion of his remarks—which were received with laughter, applause, awed silence, and even tears—appears on these pages.

During his Commencement Forum talk on the inspirational roots of his best-selling novel Roots, Alex Haley also talked about how he came to be a writer. Haley’s warm southern accents gave the large audience a cold, clear-eyed perspective on writing as a career.

Alex Haley On Writing

“So many, many people seem to feel there’s some kind of magic button,” Haley said. “But there isn’t. You do the best you can, you send stuff out, you get rejection slips, and they come back, over and over and over. I don’t know any other way to become a professional writer than to go through that.”

Haley, who has won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, began his writing career while serving in the Coast Guard during World War II. “I suspect,” said I.J. Kapstein Professor of English Michael S. Harper in introducing Haley to the Brown audience, “the full story of his writing letters for his fellow Coast Guardsmen has not been fully told. How much money he earned—a nickel, a quarter, or a dollar per letter—is nobody’s business but his own.”

After eight years of receiving hundreds of rejection slips from various publications, Haley began to be published. He completed a twenty-year career in the Coast Guard, “took a big, big gamble to become a freelance writer” living in Greenwich Village, and began to write first for Reader’s Digest and then for Playboy. “The first awareness I had of Brown University was, I guess, the best-known interview I ever did [for Playboy].” Haley recalled, “of the Nazi, George Lincoln Rockwell, who attended Brown. They gave me a choice of two subjects: One was the head of the Ku Klux Klan, the other was the head of the Nazi Party. I went with the Nazi.”

A young woman in the audience had a question for Haley. “Even though you said many writers haven’t been to college,” she said into a microphone in the aisle, “would you encourage young people who want to be writers to go to college?”

“Bless your heart, honey,” Haley replied kindly. “I’ll tell you the truth: I don’t think it would hurt you.” The audience laughed. “If there’s a problem with colleges,” continued Haley, who completed two years of college before enlisting, “as I perceive it, it’s that it might make you feel that the more elaborate your writing is, the better it is. Quite the contrary is true. Most of the best writing is the simplest writing in the world.

“Have you read Hemingway’s The Old Man and The Sea? Well, you do that before this week is over, because it’s a classic piece of work. Several of us, professional writers, tried to move a word or a comma, or replace anything in it, to improve it. And we found we couldn’t move a comma without doing harm to it, it’s so brilliant. I understand Hemingway rewrote that piece twenty-two times, standing up, with a pen.

“If you’re in college, go ahead and get your degree, but always remember this: There is no degree on earth that says, as of this receipt, editors and publishers will print what you write. Unlike other professions, writing has no finite length of time attached to its attainment. Most of the writers I know took ten years to start earning money from writing—and I mean hard work. You have just got to work, and work, and work, and keep having faith that one day it will happen. I hope it happens to you.”

Haley recalled a particular moment when he knew it had “happened” for him: “When I first got bold enough to try (to sell a story to) Reader’s Digest, I received a rejection slip with a very different, rather august approach: ‘Dear Mr. Haley: We’re sorry, but this does not quite jell for us.’ That would just frustrate the hell out of me, because I had been a cook and I would get an image of too much water in the jello.”

Years later, after Roots had been published and Haley was “hot as a pistol,” in his words, the Digest asked him to make room in his tight schedule to speak to a group of their advertisers in Detroit. After filming the “Today Show” that morning, Haley had lunch at the magazine’s corporate headquarters in Westchester County, New York. Then he was driven in a limousine to Westchester Airport.

“There sat the Reader’s Digest corporate jet, and outside it, two men with crew cuts, gray pants, blue coats, brass buttons, and the Digest logo. I walked up the runway into the plane, and I looked around at seats for about fourteen people, but there was nobody but me. One of the men came up and said, ‘Sir, if you’d like, there’s scotch, bourbon, cigars, cigarettes,’ and there was everything. There was a silver tray with all kinds of little sandwiches cut in circles, diamonds, and everything.” The two pilots went inside the instrument room and closed the door, leaving Haley alone in the seating area of the jet.

“You know how most jets go up like this,” said Haley, tracing a gradual ascent with his hand. “Well, this kind goes like this,” and his arm swooshed vertically toward the rafters. “I wished Grandma was there, and then I was glad she wasn’t because she would have been scared to death. I looked out, and the farms looked like postage stamps and my mind was running over things. You can’t comprehend what’s happening to you. All your life you’ve been wishing to God somebody’d read something you wrote, and then all of a sudden this is happening.

“Then, back to me came the thing I associated with Reader’s Digest. I remembered those rejection slips and what they said. And the thought just came to me: ‘Well, I guess it finally jelled.’

“I’ve often thought about that, because that sort of moment happens. Most writers I know have had some similar experience.”

Never forget, Haley reminded his young listeners, that rejection slips are not personal. “Part of learning to write is being rejected. The editor doesn’t know you—the person. What they are saying is, simply, you have not sent us what we will respond to. So you just keep on, and on.” ~ Alex Haley.

(Alex Haley On Writing is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. It was published in the June / July 1984, Volume 84, No. 9 issue of Brown Alumni Monthly. © 1984 by Brown Alumni Monthly. All Rights Reserved.)