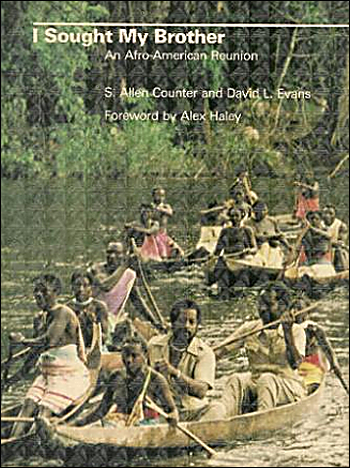

I Sought My Brother (August 24, 1981)

I Sought My Brother: An Afro-American Reunion is a unique history of a black people living deep within the jungles of South America who not only survived attempts to enslave them but who have triumphed with their original African culture intact. It also provides the only permanent record of a way of life that may soon vanish as new technologies are brought to this remote area.

The story of a meeting between Allen Counter, a neurobiologist, David Evans, an electrical engineer, and the African-descended people of the Suriname rain forest was first told in the film, I Sought My Brother, which appeared on National Public Television and in countries throughout the world. Now, in this pictorial essay, Counter and Evans condense their experiences over an eight-year period into one long reunion with the bush tribes whose African ancestors escaped into the jungle after being transported to Suriname by 17th-century Dutch slave ships. They were victorious over the colonialists during a century of guerrilla warfare, winning their independence by formal treaties before North Americans won theirs from the British. Since then, they have carried on their traditional way of life with freedom and dignity.

The book traces Counter and Evans’s discovery of this well-preserved African presence in the New World and their dangerous journey over river waters filled with rapids, rocks, and piranha that took them several hundred miles into the interior and centuries backward in time to thatched-roof villages and an exciting and highly emotional meeting with the Bush Afro-Americans. They are greeted by the headman who asks them if they are still bakra schlaffra, or “white man’s slaves,” and who wants to know if they have won their fight. “The battle is still being fought,” the authors reply.

Alex Haley contributed to I Sought My Brother: An Afro-American Reunion by writing the following foreword:

Foreword By Alex Haley

My writing of Roots was preceded by long and painstaking research to learn as much as I could about the day-to-day living patterns of the people of representative eighteenth-century small West African villages. Only then was I able to feel at least reasonably equipped to project with any accuracy the infancy and then boyhood and the youth of Kunta Kinte, the principal person of Roots And quick memories of that effort were stirred when I first heard about a pair of black scholars from Harvard University—S. Allen Counter, a neurobiologist, and David L. Evans, an electrical engineer—who had traveled deep into a jungle expanse of Surinam, South America, where few other outsiders had ever been. I heard with a thrill that they had visited the villages of a black bush people representing some three centuries of unmixed African descent—a bush people who had retained their ancestral African culture to such a dramatic degree that an equal could not easily be found today even in Africa itself.

Soon after I met Counter and Evans. They shared with me their wealth of photographs and their experiences, and a friendship was born that has not seen us very long out of touch.

It was while browsing one weekend in Harvard’s rare book library that Counter and Evans had chanced upon the memoirs of the 1700s adventurer and illustrator John Gabriel Stedman. In his words and etchings, Stedman described both his interview findings and his own eyewitness accounts of how in the early 1600s numerous Africans arriving in Surinam on slave ships managed immediate violent escapes before they could be sold, and they fled into the nearest jungles, where they battled off the successive Dutch Army expeditions sent to capture them. Other Africans already enslaved heard of the valiant fighters and also escaped to join them, until the rebellious blacks had the physical forces to begin raiding plantations for food, arms, and yet more members, including their own black women. The acutely embarrassed and beleaguered Dutch military retaliated with every imaginable savagery, and Stedman in his memoirs told and pictured the horrible carnage among both the Dutch and the blacks.

Reading over this two centuries later—after the black guerrillas had battled for generations, until their legal freedom to stay independent in the bush was finally granted—Counter and Evans were seized with what swiftly amounted to an obsession that a prime objective for Afro-American research would be to find out what had happened to those bush people.

Their determined efforts to translate their idea into action raised no few eyebrows among the number of Harvard friend and coworkers who lent them cooperative assistance. Soon, in the capital city of Paramaribo, Surinam’s president and several government ministers provided the two black Americans with a plane, a pilot, and an interpreter-guide—along with strick cautions that the bush natives must be given every respectful deference and that only their leaders could grant outsiders entry into their villages.

The next phase of the adventure moved Counter and Evans to their first self-interrogation: Was their idea really as wise as it had seemed? As extremely nervous passengers in dugout canoes, they went skimming through treacherous rapids, watching the thick boulders against which obviously any collision would immerse all hands into waters abounding with man-eating piranha—not to mention their near panic each time the dugouts passed under overhanging jungle vines and foliage from which large snakes could fall into the dugouts.

But an even more discomfiting psychic shock awaited their arrival at the first bush village. When the interpreter called out to the shoreline’s crowded loinclothed bush people that the strangers were “Africans from a place called America,” the bush people’s spokesman demanded, “Well if you are African, why are you wearing the clothes of the bakrah (white man)? . . . And are you still white man’s slaves?” Counter and Evans were stunned beyond words. “Well, are you fighting? Or have you won your fight?” Counter and Evans managed a response that the black Americans’ fight was still being fought.

I think I would do this book and its authors a disservice to attempt any condensing of what awaits readers in the pages that follow. I feel, in fact, that the more one reads, the more clearly one understands why Counter and Evans say that “neither of us could have realized just how the next few hundred miles and few days would change our thinking, our reactions, and indeed our entire lives.”

Their text and photographs graphically tell and show how they visited among people and villages “like a timewarp . . . as if we had pressed a button for the Africa of the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries.” It will come as no surprise that, following their deeply moving first visit among the Surinam jungle’s bush people, the Harvard pair returned many times.

In my opinion, this work of Counter and Evans has two principal and most timely significances. One is that recent years have see an intensifying of black petitioning that Afro-American history must become increasingly recognized both academically and among the general public. So it seems to me to follow that black scholars should undertake as a priority to lead in the varieties of field research that are sorely necessary to strengthen the corpus of the materials that document black history. There are scores of areas that offer, even guarantee, rich findings for diligent researchers—who will be not only inspired but challenged by this book.

Second, after a 300-year vigil defending and protecting their ancestral cultures and their independence, now, finally, inevitably, the Surinam bush people are facing what nearly always happens when the passage of time brings the trappings of technology with its attendant cultural erosion. For in the last section of this book, sadly, Counter and Evans tell how more and more of the younger men of the bush villages have begun to leave to take up work in nearby mining camps or other industries or in the cities—and fewer and fewer of them are returning to their native villages. What that portends for the bush culture is clear; it is only a matter of time. So this book chronicles the last days of the purity of what has been for three centuries one of the world’s most unusual cultural enclaves. ~ Alex Haley.

(The above foreword by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. I Sought My Brother: An Afro-American Reunion was written by S. Allen Counter and David L. Evans. © 1981 by The MIT Press. All Rights Reserved.)