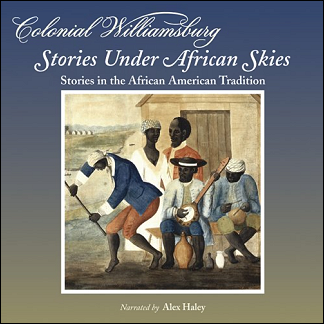

Stories Under African Skies (1992)

In chronicling the importance of storytelling to the African and African American experience, one need only realize that these stories contain the essence of the culture.

Africans

African stories contained the genealogy and cultural roots of individual black African communities. On this recording, we focus on the communities south of the Sahara Desert. Here the domestication of the land was a preeminent concern. Animal husbandry, the growing of crops, and struggling with a desolate and sometimes violent climate were a constant battle, lost or won from year to year. Famine was a reality, and food production an essential skill that literally determined the survival of most communities.

The treachery of the climate, however, was balanced by its beauty. From tropical rain forests to beautiful teeming jungles, all that was dangerous was also extremely beautiful and exotic. Out of this diverse area came the ingredients for stories that illuminate the vastness of time and place and culture. The story, after all, is a description of life itself:

An African is characteristically unable to resist an opportunity for performatory display of the joys and demands of living, and opportunities for such display present themselves in surprising variety in daily life, even in areas that to a Western mind might seem less than inspiring.

Collaborative activity in farming or cattle tending, for example, provides a constant topic to be explored. The work songs associated with black Africans throughout the world most fully display the prime value of cooperation and the coordination of energies needed to forge community. – Roger D. Abrahams, African Folktales: Traditional Stories of the Black World (New York: Pantheon books, 1983), page 5.

The African stories performed on this CD focus on living with the land and its creatures, and the often skewed line between human and inhuman, animate and inanimate, friend and foe, and good and evil.

African Americans

Lawrence Levine in his text Black Culture and Black Consciousness comments, “Although slave tales included nothing approaching the intricate genealogies and historical narratives common in the African oral tradition, they did contain a historical dimension. The tales slaves related to one another were not confined to fictionalized stories.” – Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), page 86.

Black bondsmen used stories to preserve their cultural traditions, to reach family history and values, to educate each other, to communicate with one another, and to survive the strictures of slavery. Luke Dixon, who was born in Virginia in 1855, heard such a story while sitting on his grandmother’s lap:

They herded them up like cattle and put them in stalls and brought them on the ship and sold them. She said some they captured they left bound till they come back and sometimes they never went back to get them. They died. They had room in the stalls on the boat to set down or lie down. They put several together. Put the men to themselves and the women to themselves. When they sold Grandma and Grandpa at a fishing dock called New Port, Virginia, they had their feet bound down and their hands bound crossed, up on a platform. – WPA Slave Narratives (Arkansas).

Slavery in North America presented a major change in the African’s world view. As Sterling Stuckey writes:

During the process of their becoming a single people, Yorubas, Akans, Ibos, Angolans, and others were present on slave ships to America and experienced a common horror—unearthly moans and piercing shrieks, the smell of filth and the stench of death, all during the violent rhythms and quiet coursings of ships at sea. As such, slave ships were the first real incubators of slave unity across cultural lines, cruelly revealing irreducible links from one ethnic group to the other, fostering resistance thousands of miles before the shores of the new land appeared on the horizon—before there was mention of natural rights in North America. – Sterling Stuckey, Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundation of Black America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), page 3.

Thus the stories of these transplanted Africans increased in importance and focus. Because of the need to redefine their sense of self, these stories, the remnants of a culture left only to the power of their memories, helped create a subculture complete with its own language, religion, customs, politics, and system of beliefs. Stories taught lessons of survival, communication, community cohesiveness, family values, religion, and how to get along with white folks. Stories became shields against the whip, comfort for the distressed, and hope for a better day. They were secular and sacred, serious and comic, anecdotal and true. They took the form of songs, tales, proverbs, verbal games, and “served the dual purpose of not only preserving communal values and solidarity but also providing occasions for the individual to transcend, at least symbolically, the inevitable restrictions of his environment.” – Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness, page 8.

The Music

Music is interspersed throughout the stories on the CD in keeping with the practices followed by most African and African American communities. Storytelling did not exist in a vacuum, and music was an integral part of social gathering. In fact, many storytellers were also musicians. Music was an experience that all could share. It provided transitions from one story to another and punctuated various aspects of the story itself. Music was used to create mood, rhythm, and dramatic effect, and aided in summoning the spirits of ancestors. In America, music remained a part of social gatherings in the black community. Styles changed, but the essence of the music was the same as its African predecessor:

We are almost a nation of dancers, musicians, and poets. Thus every great event, such as a triumphant return from battle, or other cause of public rejoicing, is celebrated in public dances, which are accompanied with songs and music suited to the occasion. – Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (New York: Printed by W. Durrell, 1791), page 8.

Introduction By Alex Haley

Hello I’m Alex Haley. For over forty years Colonial Williamsburg has provided the public with quality programs that teach our nation’s heritage to those who visit. More recently Colonial Williamsburg has begun telling the story of Africans—over half of Williamsburg’s 18th century population—who were the only unwilling immigrants to North America.

At Williamsburg they teach this history using a variety of methods and one of the most popular methods is storytelling. The story of the black men, women and children who helped to build this nation is integral to the history now taught at Williamsburg. Though educational by design, the selections we have chosen will intrigue anyone who is interested in history and who is entertained by a good story—stories that were first told under African skies.

Chosen as a setting is a newly constructed slave quarter at Carter’s Grove—a plantation owned and operated by Colonial Williamsburg. The location was selected because it is a realistic rural place where African Americans are symboled to share stories. The atmosphere among the people gathered at the slave quarter under a full moon with only the accompanying sounds of birds, animals, and other creatures of the night hearken back to an authentic time and place. It is hoped that a scene will be evoked in the listener’s imagination similar to this one described in 1869 by Thomas Higginson, a colonel in the Union Army:

Strolling in the cool moonlight I was attracted by a brilliant light beneath the trees, and cautiously I approached it. A circle of thirty or forty soldiers sat around a roaring fire, while the old uncle, Cato by name, was narrating an interminable tale, to the insatiable delight of his audience. It was a narrative, dramatized to the last degree; and even I never witnessed such a piece of acting. And all this, with the brilliant fire lighting up their red trousers and gleaming from their shining black faces. This is their university; every young Sambo before me, as he turned over the sweet potatoes and peanuts which were roasting in the ashes, listened with reverence to the wiles of the ancient Ulysses, and meditated on the same.

Those blacks who were brought to South America, North America and the Caribbean all sprang from one homeland—West Africa. While their conditions would differ from place to place, the root of their culture and experience was similar. The stories you are about to hear sprang from that common West African beginning. ~ Alex Haley.

Secular Introduction By Alex Haley

Once Africans arrived in North America their sense of community, culture, geography, and station changed dramatically. Their stories changed to accommodate the need to develop a new system of survival. Stories were told which helped educate slaved men and women on what to say, when to say it, and who to say it to. ~ Alex Haley.

Religious Introduction By Alex Haley

African American religion can be described as a hybrid combination of African traditions and Christian doctrine. There’s no doubt that African Americans developed their own version of Christianity—especially during the later part of the 18th century. Simon Brown, an ex-slave born in 1843, recounts a story outlining this religious divergence. ~ Alex Haley.

Conclusion By Alex Haley

African American storytelling continues its strong tradition today. We have focused on storytelling and its value in teaching history. But its overall importance to the black experience is as fundamental as language itself. Its importance to the community today is just as significant as it ever was. But in this era of technological advancements, and satellite communications, storytelling has adapted to contemporary sensibilities and patterns of understanding. African Americans are still consummate storytellers but they do it as performers, actors, musicians, folklores, preachers, teachers, commentators, politicians, and even historians. Traditions have evolved to satisfy today’s needs, but they each and all began under African skies. ~ Alex Haley.

Stories Under African Skies • Stories In The African American Tradition

Narrator: Alex Haley January 1, 1992

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Audio Player

Narrator: Alex Haley January 1, 1992

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Narrator: Alex Haley January 1, 1992

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Narrator: Alex Haley January 1, 1992

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

“Stories and music were essential to African culture, and to the African American culture forcibly transplanted into the New World. This recording, with a special narration by Roots author Alex Haley, brings together the stories of these uprooted Africans and some of their music.” – The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The above text and audio narrations are presented under the Creative Commons License. Stories Under African Skies: Stories in the African American Tradition. © 1992, 2005 by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All Rights Reserved.)