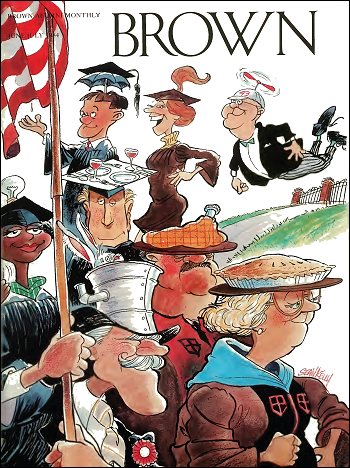

(Alex Haley’s Better Day is from Alex Haley’s commencement speech he delivered to an audience in Alumnae Hall at Brown University on May 26, 1984, which was published in the June / July 1984, Volume 84, No. 9 issue of Brown Alumni Monthly.)

Alex Haley’s best-selling novel, Roots, based on his family’s history, was made into the most-watched television program of all time. Earlier Haley pioneered the “Playboy Interview” format for Playboy magazine, and was co-author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Alex Haley was at Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island) for the graduation of his niece, Anne Palmer Haley—the daughter of his brother George Haley. Haley spoke at a Commencement Forum on Saturday, May 26, 1984 to an audience of some 600 in Alumnae Hall where he spun tales of growing up in the South and the flowering of his novel Roots. A portion of his remarks—which were received with laughter, applause, awed silence, and even tears—appears on these pages.

Haley ended off on his commencement speech with: “I am so aware that all of us, we in this audience, everywhere, we are the descendants of the people in that microcosm scene [the whipping scene in Roots]. Descendants of those slaves, descendants of the overseers, of the owners, or whatever. We are generations, centuries, since then, and without any question, our day is infinitely better.

“My niece Anne and her classmates are graphic reminders that it is so much better than it was in the time of Kunta. The rest of us, in our very attitudes, are no less graphic reminders that it is so much better than it was with the overseers and the owners. I think that what we now represent is an exciting potential, and that we can continue to get it together and discover each other. I’m so glad the symbol of Roots [the movie] was the father holding up the little baby to the sky and saying, ‘Behold, the only thing greater than thyself.’ ” ~ Alex Haley.

Alex Haley’s Better Day

Thank you for the reception you give. I always get a kick out of standing back in the wings listening to all these things that get said. I stand back there and think, “I wish Grandma could hear this.” Because the fact is, none of it ever would have happened—certainly not Roots—had it not been for my grandmother.

Thank you for the reception you give. I always get a kick out of standing back in the wings listening to all these things that get said. I stand back there and think, “I wish Grandma could hear this.” Because the fact is, none of it ever would have happened—certainly not Roots—had it not been for my grandmother.

We were raised in a little town called Henning, Tennessee. It’s about fifty miles north of Memphis, and the population at that time was about 550 people, and it still is today. The next book I will be doing will be titled Henning. It’s about people and events in that little town during the 1930s when we were boys growing up there. It is about a specific town, but in another sense it’s a commentary on little towns per se, because they all are similar in many respects. Whereas in cities people do all kinds of things trying not to be anonymous, in little towns you didn’t have that problem because everybody knew you to start with. By the time you were in your latter teens, people had singled you out with something that wouldn’t get you far in a city, but it was big stuff in a little town. The lady who cooked the best apple pies, the tallest boy, the strongest man—any such thing would do it in a little town. I’m having a lot of nostalgic fun writing about that seemingly inconsequential community, and the people among whom we grew up, who—as we say in the South—raised us.

In 1969, Hugh Hefner invited all the people who contributed to his magazine, Playboy, to come to Chicago. We did, a great many of us, I guess about 150. And of that 150, eighty-four were writers. I don’t know if that many top-grade writers have ever been in one place at one time before or since.

Because there were so many writers present in one place, all the journalism students who could get there from anywhere proximate to Chicago came and questioned us, distributed questionnaires, to learn as best they could what made writers tick. One of the fascinating things they found was that of the eighty-four writers, four had finished college. The other thing was that a little bit more than two-thirds of us had come out of the U.S. South.

Almost involuntarily, those of us who were southerners began to draw away from the others and just discuss among ourselves why was that. What we arrived at was that we, much more than the others, had grown up in a regional culture where of evenings the family would gather for its entertainment either in the front room or on the front porch. The elders would talk and the kids would listen; thus we had grown up in a storytelling culture.

I can remember as clearly as if it were last week how Roots began, long before I ever had any thought of, or before I could even have spelled, roots. My grandmother Cynthia Palmer—everybody called her Sis—was all over the place in this little town. She was gregarious, full of fun, full of everybody’s business. Our grandfather Will Palmer—I was only five when he died—was a tall, straight black man who was the first great hero I ever had in my life. When he would come in he had a way of putting his finger down that was a signal for me. If he put his right index finger rigidly down, it meant I could take my little fist and grab that finger and he was going to take us walking. I remember walking with him with my head down, and I would watch the way when his foot swung forward the pants cuff would kick against the instep of his shoe and by the time that foot went down the other one would pick up. I would be taking about three little skipping steps to match his one.

We would, from time to time, meet people. He was a big man in town; he owned a lumber company. Southerners are very courteous, and people would say, tipping their hats, “How you do, Mr. Will Palmer,” and he would speak to them similarly. I remember the sense that Grandpa was somebody, and I was very proud to be affiliated with him, hanging there onto his finger. Every now and then somebody would make some reference to me, like, I was growing well, I seemed bright, or something like that, and Grandpa would always say the same thing. He’d say, “Well, he’ll do.” I had heard Grandma say that Will Palmer would tear up a nest of wildcats if they’d mess with me, so I knew he was just being modest about what he really felt.

Henning represented to us—principally because of our grandparents—a kind of nest. I can’t imagine having been able to grow up with a more idyllic sense of being loved and secure. To this day, if you tell me anybody is somebody’s grandma, I just want to go hug her, because I feel that way about grandparents. For little children in particular, nobody on earth can do what grandparents can do. Grandparents kind of sprinkle stardust over the lives of little children.

Grandpa and Grandma were like one person. The whole community regarded Will and Sis Palmer as a unit. I remember a thing that emphasized how our grandfather was stiff in his way, externally. He was a businessman in his soul. He had finished the fifth grade somewhere, but innately he had this business acumen.

I always liked to fiddle around in things historical, to do things like poke around up in the attic and look for things—you know. Mama’s high-button shoes in the old trunks. One time, I guess I was about fourteen, up in that attic in Henning I came upon a pile of letters tied with a blue ribbon, faded. I opened the ribbon, and I’m fiddling around looking at the letters and the way people used to express themselves. Then I came upon a letter that absolutely delighted me, because it obviously was the very letter with which our grandfather had proposed to our grandmother. I thought that was a scream, and I went tearing downstairs with it to where Grandma was cooking. When she saw what I had, she affected great anger and said, “Boy, I’m going to knock you in your head.”

But you know when your grandmother is not really mad, and pretty soon she said, “Boy, sit down.” And I can quote the letter to you exactly. Our grandfather wrote:

“Dear Cynthia:

“Inasmuch as we have now been keeping company for two years, I feel it is time we should discuss the contract of marriage.

“Yours sincerely,

“William A. Palmer”

Grandma got this wistful, nostalgic look and said, “I remember as if it were yesterday.” Then she described how a boy had come and delivered the letter by hand to her of a Saturday afternoon, and apparently that was a big deal to have something delivered by hand. She read it, and when she understood it she went screeching in the house at the top of her lungs to her mother and her sisters, hollering, “I got ‘im, I got ‘im!” And indeed she did, and in a very direct sense that was the beginning of me and the rest of us.

They had been like that, and then abruptly Grandpa died. It was rather as if an eclipse had come in the house. All that had been bright was now the opposite. Everything that had been animated was now tomb-still. It wound up with Grandma sitting on the front porch in a white wicker rocking chair like a recluse. People she’d known all my life, who were good friends of hers, would pass by on the dirt road outside. They would say, “How you doin’, Sis?” and she sometimes wouldn’t even acknowledge old friends, but nobody minded because they knew how desolate, depressed, distressed she was.

Then, it seemed after a long time, Grandma got the idea that she had to do something to snatch herself out of it, and she began to write letters to her six sisters. Grandma wrote phonetically. She would spell out a word until it sounded right to her, and then she would write character by character, slowly, on narrow-lined tablet paper, one page per letter. She told me the six of them, seven including herself, had not been together since they were girls living in a place called Alamance County, North Carolina. She was inviting each of them to come and spend all or part—whatever they could—of the next summer with her.

About two weeks after each letter was mailed, Grandma would get one back from one of the sisters saying when they were coming and how, by bus or the Illinois Central train. Grandma would get the undertaker’s calendar that hung above the washbasin in the kitchen and put the name of who was coming. On that day we would go downtown. Grandma would put on her downtown hat; it had a feather with a forty-five degree angle on it. The bus or train would come and they would get off, and there would be all this hugging and kissing, and then we would troop home.

In that manner, the summer that I was six and my brother George was two, six sisters gathered. I remember seeing any two of them come together in the house, and they would just kind of reach out and clasp palms on each other’s shoulders at arm’s length and look right in each other’s faces and laugh. It was simply because they were so happy to see each other again.

Every evening we would have supper, as the evening meal is called in the South, the dishes would be collectively washed, and then the sisters would all start trickling toward the front porch. It was about the time when dusk deepened into early night. There were numbers of rocking chairs on the front porch and anybody could sit wherever they chose, except nobody but Grandma sat in her white wicker rocking chair. I always stood right behind her chair because it seemed to me somebody should look out for Grandma and it should be me; I was the oldest. George was very frequently in her lap. All around the front porch were thick honeysuckle vines, and there were lightning bugs flicking on and off over the honeysuckle. Anybody who’s lived in the South knows how honeysuckle smells particularly heavily sweet in the first cool of the evening of the summers.

Nobody planned these things; it was just what happens on front porches in the South of evenings. First thing was, they had to get the rocking together. You don’t just sit down in a rocking chair and start rocking. You’ve got to get it maneuvered to just the right angle, and only you know what’s just the right angle. Then, some people have a quick, kind of nervous rock, and other people have a more languid, slower rock, and it would take maybe five minutes to get the rocking synchronized. Then every hand would run down into an apron pocket and come up with little tin cans of snuff and load up their lower lips. They’d take practice shots, and easily the champion in that department was our great-aunt Liz, the only one that wasn’t married ever, who had come from Oklahoma, where she’d been teaching for a long, long time. Aunt Liz could drop a lightning bug out there in the dark at six yards when she was in good form.

Once they got the rocking together, and the snuff dipping together, they would start talking about when they had been girls in this place called Alamance County, North Carolina. As a rule, the earlier part of the talking would have to do with girlhood mischief. I remember much talk about somebody who had stolen, from under their mother’s eyes practically, a mason jar of canned peaches, and they had eaten the peaches, and their mother went to her grave never knowing who got those peaches. There were other things that different ones would tell, and they’d say, “I never told that ’til this day,” and they would all just laugh at their girlhood pranks and mischief and whatnot of fifty, sixty years before.

Then they would talk about their father: Strict, stern; his name was Tom Murray and he was a blacksmith. He had vowed as a slave that whenever he got free he would own his own blacksmith shop. They talked about their mother. She would get indignant when people called her Irene, as people liked to, because her name, she would always insist, was A-R-R-E-N-A, Arrena.

Now and then Grandma and her sisters would start waggling their heads, and their expressions and tones of voice would become kind of doleful, and they would say things like, “Ah, he was just scandalous.” I came to know that they were getting ready to talk about their father’s father. He was somebody they said was always fighting gamecocks, chickens, and he was called Chicken George. He was always into some rambunctious this, that, or the other, and he was always sinning a whole lot. There was one sin in particular, I didn’t understand what it meant, but it seemed he did a lot of it. It was called womanizing.

They would frequently tell about Chicken George’s mother. Her name was Miss Kizzy, and she didn’t talk a whole lot, but they said when she did talk, people would listen carefully to what she had to say. She did not live in North Carolina; she had lived somewhere called Spotsylvania County, Virginia. Least often of all they would talk about her father, whom they described as the African. They said his name was Kinte, and they would tell a few little things that had come down across the generations, sounds that he had made, African sounds, identifying different things.

My grandmother, her sisters, George on Grandma’s lap, me standing behind the chair—all of us were engaged in something, but we had not the slightest dream, none of us, that we were involved in the oldest means of human communication of knowledge, called oral history. The memories passed through the mouths of the elders into the ears of the young.

During the same period of time, there in deep-southern, Bible-belt Henning, Tennessee, I was involved in something that was the case with every child in town. In the religious perspective of Henning, Tennessee, everybody was either Methodist, Baptist, or a sinner. In that context, all children went to Sunday School. I grew up hearing two sets of stories—those told by my grandmother and her sisters, and the biblical parables told in Sunday School. By the time I was eleven or so, my head was a jumble of David and Goliath, Chicken George, Tom the Blacksmith, Moses, so forth; they were all kind of mixed up. I would have had to stop and really think about it to separate who belonged in which set of stories.

I go to this length to establish how it happened that I grew up with a pretty strong sense of family story, simply because I’d been so exposed that summer when all six sisters came, and in subsequent summers. Never again was the whole set of sisters together, but there’d be two, three, every summer and they would talk, talk, talk about this story, or facets of it. I learned it in that way and it was almost indelible.

Some of us have had the experience, I know, of talking with very elderly members of our families, or elderly people not of our family. They might not be too sure about what happened last week, but they can tell you exactly what happened when they were seven, eight, nine years old. That is because all of our memories tend to be more retentive of those things we learned earliest on, when our minds were less cluttered with competitive things for space and permanence. And that’s how that story stuck with me.

Our father was a college professor. He’d come out of Cornell with a master’s degree. It tickles me to remember that in Henning, people didn’t know what a master’s degree was. They knew what college was because our Mama had been, and our Daddy had been, and a few white teachers in town had been. But the master’s degree kind of threw people. We had a lady in our town called Sister Scrap Green. Whenever things puzzled the black community, it was generally Sister Scrap who would finally figure out what the thing was, and she would tell people the explanation for it. Thus it was with this mysterious master’s degree. One day Sister Scrap called some people together after church and said she had figured out what this master’s degree was that Professor Haley had. She told them, “Well, what it is, is all the learning one man’s head can stand.”

Our father, bless his heart, was not what could be called a modest man. Down in Henning he would talk to little groups of people who would just gather around him. They figured he knew so much that if you got close, some of it might rub off on you. Dad had a habit when he would talk to people—he acted as if it were accidental—he had this key chain that went from vest pocket to vest pocket, a thick kind of chain. Down from that hung a fine chain, sort of like you see ladies wear around their necks, and from the end of that was a little key symbolizing, I guess, some fraternity he had joined at Cornell.

Dad would just start swinging his key, and people would be there in the audience and you could almost see them goin’ like that [moves his head from side to side], following the key. His dear friend and avid admirer, this same Sister Scrap, cured him of that. One day when Daddy was swinging, she just asked him directly before this group, “Professor Haley, what is that?” and she pointed at the key.

Now that was all our father wanted to hear. He launched into a Greek and Latin description of the key’s derivations and everything which the audience understood not one syllable of. And when he ran down, Sister Scrap hit him with another question. She said, “First thing, what do it open?” I never forgot that, because Dad stood there with his mouth going: He couldn’t tell her what it opened. From then to this day, whenever I meet somebody who’s pompous and proud of themselves and all, in my mind I ask, “What do it open?”

Anyway, that time, that town, those people, those stories, were the genesis of Roots. I will jump over, in the interest of time, all the interim things.

After the manuscript [of The Autobiography of Malcolm X] was gone to press, I was like a lady who’s just had a baby. It’s something you’ve been full of a long time and all of a sudden it’s gone, and you don’t quite know what to do with yourself.

I was thus, one Saturday morning, in Washington; I don’t even remember whom I had interviewed or for what. I came out around 12:30 and I saw this big, tall building, with big, tall columns, and above the columns were the words, U.S. National Archives. It was just purest caprice: I didn’t have anything else to do, and the historical potential of that word “archives” got to me, so I wandered up the steps. In the lobby there were tables with thick glass tops (containing) documents which had to do with the founding of this country. In the background there were big photographic blowups of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. The whole atmosphere was of the history of the United States of America being revered, treasured.

I wandered up into the main reading area, and a young white fellow came up to me and said, “Could I be of service to you?” I somehow got together a question that did not say directly what I really was curious about. I’d been thinking about it of recent times, so I said, “I wonder if I could see the census record for Alamance County, North Carolina, 1870.”

Many times since, I’ve thought back on that. I don’t believe anybody had said “Alamance County” to me, or in my presence, since I was a little boy on that front porch with Grandma and our great-aunts. I think I remembered the words Alamance County much the same as I would have remembered Galilee or Jerusalem from the stories I’d learned in Sunday School. And I said 1870 because somewhere I had heard that the first time black people were listed by their names in the census was following the Civil War, which would have been 1870 on decade intervals.

The young man told me I should go up in the microfilm room, and I did. They sent up eight rolls of microfilm. I remember threading one in, and you know you look down through this scope, and you turn the handle . . . I went through the whole first roll and it was at first intriguing, then it became almost eerie. I was feeling, “Wow, here are these people long in their graves, and this may be the only record there is of them in this world. Just this one line, and maybe there are a lot of people who didn’t even make this line.” I turned the handle rapidly and it seemed they walked briskly along. They had become now animated to me. Then I turned the handle more slowly and it seemed they walked with stately calm.

I went on looking and looking. In the sixth roll, it was almost as if a fist came up out of that thing and hit me with its impact. I’m looking at “Murray, Thomas”; his age; color—B stood for black; occupation, blacksmith. How many times had I heard Grandma and Aunt Liz and Aunt Plus, all of them talk about their daddy, Tom Murray, the blacksmith? And then if there was any question, right underneath his name was “Wife, Arrena.” How many times had we heard Grandma and all of them talk about their mama insisting her name was spelled that way, not “Irene?”

Beneath their names were their children at the time. I’m looking at the names of our great-aunts, but for Pete’s sake, their ages—twelve, fourteen, thirteen, eleven, like that. And it was just unbelievable, because they had been to us gray-haired ladies. I remember the astonishing thought, “Look, let me get to Grandma, she’s the reason I’m here.” Almost simultaneously came the thought that used to confuse me so much as a little boy. The rest of them would always call her the baby, but how in the world is somebody’s grandma a baby? I dropped to the bottom of the list, and the shocker: no Cynthia. It really threw me for a moment, and then it suddenly dawned: Grandma wasn’t even born yet. Grandma was born in 1872; this is 1870.

As best I can recall, that was the first bite of the genealogical bug from which anybody involved in it knows there is no cure. For the rest of your living days you will be involved in digging for one more little scrap of information. You will get to the point where you’ll say, I’m sick of this mess and I’m not going to throw my whole life away doing it. Two days later you’re back at another dusty pile of records, and you just can’t help it. That was what led into Roots.

By 1972 I was up to here with that research, and I was fervent about it. I was just spilling over with what had come to be my whole existence—that story. I had come to see it not just as our family story; in fact, that was almost incidental. I had come to see it as a symbol story of a people, because all black people have fundamentally the same story. Every black person goes back to some Kunta Kinte or his female counterpart somewhere in West Africa, who was brought to this country on a slave ship into a succession of plantations, and then struggled for freedom from that day to this. Roots was a symbol story in a world where we all, I think, desperately need to know more about each other, the better to understand and to be aware of each other.

Anyway, it was published. I didn’t have any dream that it would be even successful; I just was very caught up with it and had to do it. When it came out it really did go wild. The first awareness I had that it was something special [was when] I began to get long-distance calls from my agent and publishers. Before the book, when they’d call me they had something very specific to discuss, but now they’d call and say they just wanted to know how I was feeling. Nobody had cared about how I’d been feeling up to that point. All of a sudden, they cared.

The most emotional thing that ever happened to me with Roots was when we were making the film. I’d had no dream that it was going to be a film, and now six of us had to read the book clinically, looking for the scenes that we were going to use in the film. If you filmed everything in a physically big book like Gone with the Wind, Roots, Shogun, any of them, the film would last two weeks. You have to get the best, or the most filmable scenes, and put them together in some kind of chronology with bridges, with various other devices, and hope it carries the thrust of your book.

Anyway, six of us read Roots and we arrived at some acceptance of what we would film. One afternoon at ABC headquarters, I was just talking and I told them I sat at the typewriter and wept trying to write one scene. I wept at a lot of scenes, but that one in particular. I said I’d just like to ask that when we make this film, no scene in the film would be stronger than this one. They said, okay, what scene is that? I said, that’s where Kunta Kinte fought to keep his name. And everybody agreed.

We were filming that particular scene in Savannah, Georgia. We spent all morning rehearsing because it was a long scene and it had to be done in one piece; you couldn’t break it up and then patch it together. We spent all morning with tapes measuring everything, sound-level things, state-of-the-art everything, using stand-ins for the actors. Finally around 1:30 the magic call came: Action.

Playing Kunta, strung up by his wrists to a pole overhead, was, of course, LeVar Burton. Playing Fiddler, who had trained him, was the incomparable Lou Gossett; and playing the overseer was the late Vic Morrow. Vic was one of those actors who could make you completely forget who he was, because he became the character. He made me so mad sometimes playing that evil overseer, one afternoon I told him, “Look, I’m sorry I created you.”

The situation was that the master had decreed that the slave, Kunte Kinte, should be named Toby, but the slave would always refuse to say it. Fiddler had begged him, cajoled him, threatened him, everything he knew how, but that young African would never say his name was Toby; he’d always say he was Kunta. So the master had given the word that for this insult, this insubordination, the African would be beaten until he would say “Toby.”

We had three cameras, double-loaded, state-of-the-art sound on mikes that pick up a whisper, and about thirty of us just out of camera range with bated breath, praying it would go all the way through. There was a time later on that Norman Lear was telling me, “Alex, you can get the best cinematographers, the best directors, the best money can buy in every department. But sometimes a miracle will happen out there in front of that lens.” It happened for us that morning in Savannah.

The action started. Vic Morrow, in a cloak, strolled into camera range and looked at Kunta strung up and said, sneering, “What’s your name, boy?” LeVar said, confidently, “Kunta.” And Vic kind of chuckled a little and nodded at another slave to begin the beating, and this fellow raised the whip and began three lashes. The whip was made of loosely woven hemp. Every time it would touch LeVar’s back, his toes were on little blocks and he would arch forward and strain his muscles and look as if the whip just jerked him forward.

After the third blow, the makeup people’s stuff was going and it looked like blood; it looked terrible. Again Vic said, “What’s your name, boy?” and again LeVar said, “Kunta.” Now, slowly, three more lashes. At the third blow it was very evident, with LeVar’s head lolling, that he simply couldn’t live through much more of that. And then, as scripted, LeVar volunteered. He said, “Toby, massa.” Vic turned triumphantly and said, “Louder. Let me hear it again, boy. What’s your name?” And again LeVar said, “Toby, massa.” Then Vic said, “Cut him down.”

Now we had scripted that he would be cut down and he’d slump into the lap of Lou Gossett—Fiddler—and Lou was going to put his arms around LeVar and be solicitous and mother him. We were going to film a little of that, and then we were going to slowly throw the lens out of focus—you’ve seen these films that end with things just going watery. That was the plan, but here’s what happened.

When LeVar slumped, he slumped perfectly in Lou’s lap, and all of us were praying that it would keep on going. All of a sudden we saw veteran actor Lou Gossett’s face burst into sobs, and he wasn’t acting; that man was crying from his gut. There’s something about a grown man crying that gets to you to start with, particularly a Gossett-type guy, strictly macho. Lou was just sobbing, and he meant that thing, and we’re looking and don’t know what in the world to make of this.

Then Lou opened his mouth and began to talk. He said. like it was tearing from him, “What difference it makes, what your name is, what they call you? You knows who you is. You’s Kunta.” And Lou convulsed again; his whole body seemed to tense and his arms tightened. His hand went up under LeVar’s chin, he turned LeVar’s face, and he’s looking right into his eyes, like a mother might her infant. And Lou spoke: “They’s gonna be a better day,” and there was a little hesitation and he spoke it again: “They’s gonna be a better day.” I guess within ten seconds, click, click, click, the film ran through three cameras, the last film, and we used every frame of it. It was easily, far and away, the most powerful scene in the whole of Roots.

Afterwards we were all over Lou; we were very moved. We said, “Lou, what in the world happened?” Lou said, “Man, I don’t know. All of a sudden I was 150, 200 years ago. I forgot all about being Louis C. Gossett, Jr., actor. I was Fiddler and that was my little guinea boy, and my job was to teach him how to be a slave. But what had happened was that he taught me how to be a man.”

I never forgot that thing. And I never forgot what he said: “They’s gonna be a better day.” I am so aware that all of us, we in this audience, everywhere, we are the descendants of the people in that microcosm scene. Descendants of those slaves, descendants of the overseers, of the owners, or whatever. We are generations, centuries, since then, and without any question, our day is infinitely better. My niece Anne [Anne Palmer Haley ’84, George Haley’s daughter] and her classmates are graphic reminders that it is so much better than it was in the time of Kunta. The rest of us, in our very attitudes, are no less graphic reminders that it is so much better than it was with the overseers and the owners. I think that what we now represent is an exciting potential, and that we can continue to get it together and discover each other. I’m so glad the symbol of Roots [the movie] was the father holding up the little baby to the sky and saying, “Behold, the only thing greater than thyself.”

I know I’ve talked too long; I can’t help it. Thank you. ~ Alex Haley.