(Alex Haley Remembers was originally published in the November 1983 issue of Essence Magazine. In 1992, it was then was published again within Malcolm X As They Knew Him by David Gallen.)

(Alex Haley Remembers was originally published in the November 1983 issue of Essence Magazine. In 1992, it was then was published again within Malcolm X As They Knew Him by David Gallen.)

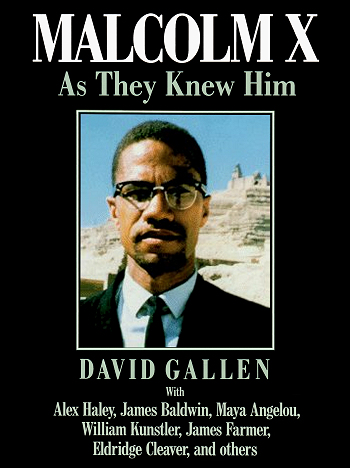

Malcolm X As They Knew Him

Part One of Malcolm X: As They Knew Him presents the remembrances of twenty-five men and women whose lives were dramatically touched—and in some cases radically altered—by Malcolm X. In their own words, extracted from recent interviews with David Gallen, they illuminate divers facets of Malcolm’s dynamic character and career.

Writer Maya Angelou, for instance, speaks of the contemplative Malcolm she knew in Africa, while newsman Mike Wallace recalls Malcolm’s last daring media appearances. Alex Haley provides intimate glimpses of the private man, and Benjamin Karim shares his memories of Malcolm lecturing on the swine and teaching lessons in charity all the way from Harlem to Bridgeport, CT.

In the minds of those who knew him Malcolm is still vividly there: eating banana splits, quoting Shakespeare, driving his old blue Oldsmobile home to East Elmhurst, growing a beard. A man stands behind the myth.

Destiny has made of Malcolm X a legend, symbol martyr, saint, hero, prince and inspiration. Alex Haley knew the man. Over a two-year period, from 1963 to 1965, Haley conducted the fifty interviews with Malcolm that produced both The Autobiography of Malcolm X and a close, warm, trusting friendship between the two collaborators.

In this remembrance published in Essence magazine in November 1983, nearly two decades after Malcolm’s death, Haley recalls the man he knew—the family man as well as the public man—and honors the trust of his friend.

Alex Haley Remembers

Time passes so swiftly, but I’m still astounded that it really is eighteen years since that Sunday in February 1965: Malcolm X, then thirty-nine years old and known as El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, had begun to speak in Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom when suddenly gunfire erupted and he fell bleeding from multiple wounds. He was rushed to the hospital, where surgeons tried desperately to save him by opening his chest for direct manual heart massage—but soon a hospital spokesperson or somebody told the press and the swelling, weeping, almost mutinous crowd that had kept vigil, “The gentleman you know as Malcolm X is dead.” Through the two years before then, I’d been privileged that Malcolm had given me about fifty lengthy and probing interviews to use as the basis of a book chronicling his life. Now and then he would comment that he wouldn’t live to see the book published—and he was right.

During 1960, Reader’s Digest had commissioned me to write an article about the ten hotly controversial Black Muslims. I first met Malcolm when he was their chief spokesperson. The next year I interviewed him for Playboy. The article offered a glimpse of a precocious child growing up in a small Michigan town through the Depression years who then became a teenage hustler in a Boston ghetto, moved on to Harlem and heavier crimes, was eventually arrested and convicted and served over six years in a penitentiary. By the time of his release he was an impassioned convert to the Nation of Islam, of which he ultimately became its most publicized minister and national spokesperson. A book publisher wanted me to obtain Malcolm X’s full life story, and finally Malcolm agreed, while cautioning me sternly, “A writer is what I want, not an interpreter.” I was elated to try my first book with a subject so obviously exciting.

Usually two nights a week, sometimes three, Malcolm would park his blue Oldsmobile somewhere near my Greenwich Village apartment. It was probably bugged by the FBI, and always Malcolm would snap, “One, two, three—testing!” when he first came in. Next he’d telephone his wife, Betty Shabazz, tell her where he was and jot down messages she gave him. Then, rather than take a seat, for the first half hour, at least, he preferred pacing the room like some caged tiger, talking nonstop about the Nation of Islam and its leader in Chicago, Elijah Muhammad. Whenever I’d gently remind him that the subject of the book was him, Malcolm’s hackles would rise. One wintry midnight, however, in sheer frustration I blurted, “Mr. Malcolm, could you tell me something about your mother?” He turned, his pacing slowed, and I’ll never forget the look on his face—even his voice sounded different. “It’s funny you ask me that . . . I can remember her dresses, they were all faded out and gray. I remember how she bent over the stove, trying to stretch what little we had. . . .”

It was near dawn when Malcolm left for home, having spilled from his memory most of what I’d later use in the first chapter of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, appropriately titled “Nightmare.” It tells the story of the small boy, Malcolm Little, one of eight children watching their mother’s struggles to keep the family intact after the brutal, racially motivated murder of their father, a militantly outspoken Baptist minister and supporter of Marcus Garvey. After that session Malcolm never hesitated to relate any aspect of his later life in the most detail his memory could muster. And I find myself now experiencing a diversity of emotions as I recall random memories of that truly singular and very special human being.

I think my most indelible memory is of how ably he maintained his characteristic manner of controlled calm, when actually he lived amid a veritable cauldron of private and public pressures. Easily the source of most intense pressure was his role as the Nation of Islam’s most public figure, while in fact he had been made virtually a pariah within the organization’s top hierarchy. This status was due to, as Malcolm put it, “jealousies caused by others’ refusal to accept that, when I did my appointed job as the Nation’s spokesman, inevitably publicity would focus on me. I think Mr. Muhammad understood that, until others poisoned his mind against me.” Nearly a year of our frequent interviewing had passed before he astonished me with a hint of that later public revelation.

Nonetheless, he carried on as “spokesman,” maintaining such a grueling public-speaking schedule throughout the United States that some weeks he caught airplanes like taxis. And his blue Oldsmobile stayed on the go when he was in New York. There, particularly, he often faced hostile media people, and this helped him hone his verbal agility into practically an art form.

Malcolm was a master at deftly goading white verbal opponents into such a fury that they could only sputter almost incoherently. “The more the white man yelps, the more I know I have struck a nerve,” Malcolm said. A hundred times, if once, I watched his face suddenly crease into a foxlike grin as an angry opponent struggled to retain composure, and then Malcolm would fire verbal missiles anew. He would turn a radio or television program to his advantage in a way he credited to the boxing ring’s great Sugar Ray Robinson, who would dramatize a round’s last thirty seconds. Similarly Malcolm would eye the big studio clock, and at the instant it showed thirty seconds to go, he’d pounce in and close the show with his own verbal barrage.

Malcolm was at his most merciless with any black opponent who he believed dared to publicly defend whites. His worst victim, probably, was a famed Harvard University associate professor (who was also a Ph.D.), in their widely publicized debate. The professor had been continually attacking Malcolm as a “divisive demagogue” and a “reverse racist” when Malcolm, in the debate’s closing seconds, fired back, “Do you know what white racists call black Ph.D.’s?: ‘Nigger!’ ”

But there could also be quite another side of Malcolm X. I just have to laugh, recalling one night during our interviews when he was reminiscing about his finesse as a dancer. Springing up suddenly, with one hand grabbing a radiator pipe to represent a girl, he wildly lindy-hopped for maybe a full minute before suddenly stopping. He sat down, clearly embarrassed, and was practically surly for the rest of that session.

And I remember Malcolm one time laughing so raucously that he could hardly tell me the details of how he had once been menaced in his prison cell by an armed guard and how he had struck instant terror into the man. Abruptly jerking him so close that their noses touched, Malcolm had hissed, “You put a finger on me, I’ll start a rumor you’re really black, just passing for white!”

And I remember a late afternoon when we happened to be interviewing in a Philadelphia hotel room. A pretty lady volunteer telephoned, then visited, bringing only half of some important typing she was doing for Malcolm and saying that he should pick up the rest at her apartment later. It was obvious to us both: she had eyes for Malcolm. He fretted and stewed and finally asked me to take a taxi and make the pickup. When I returned to my room, the phone was ringing, with Malcolm demanding, “What else did you do, because anything you did wrong was in my name.” I told him that as mad as that woman had been when I turned up, there was no way anybody could have damaged his name with her.

“I must be purer than Caesar’s wife,” Malcolm would often say, hypersensitive that any hint of wrongdoing could so easily become gossip capable of damaging his public image and credibility. And that public presence was indeed so awesome that wherever Malcolm appeared, it was rather like witnessing a force in motion. I saw the man’s impact on people many different times and ways. On one afternoon when we were driving in Harlem, Malcolm suddenly jammed on the brakes and sprang from the car. Running across the street, to the sidewalk, Malcolm crouched like an avenger over three young black men whom he’d seen shooting dice near the entrance to the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature and History, as it was then called. “Beyond those doors is the world’s greatest collection of books about black people!” he raged at the young gamblers. “Other people are in there studying your people while you’re outside shooting craps!” The three practically slinked away before Malcolm’s wrath. He used to exclaim, “Man, lots of times I just wish I could start back in school, from about the sixth grade. Man, I’d be the last one out of that library every night!”

Although Malcolm X was acutely aware of the physical risks he steadily faced, he was determined not to let the danger muzzle his voice or inhibit his activities. He felt that his greatest safety lay in really trusting only a few people—and those few only to certain degrees. The late author Louis Lomax and I used to laugh about how we didn’t discover until much later that once Malcolm had visited and given each of us interviews in different rooms in the same hotel, with never a mention to either about the other, although he knew well that Lomax and I were good friends. When Malcolm and I began the book project, he told me candidly, “I want you to know I trust you twenty-five percent.” (Much later I felt great personal gratification when he upped the trust to seventy percent.) Now or then during our interviews he’d mention some people who seemed to me quite close to him—adding a startlingly low trust percentage.

Squarely atop Malcolm’s trust list was his wife, Betty Shabazz, of whom he said, “She’s the only person I’d trust with my life. That means I trust her more than I do myself.” He felt genuine admiration for her, even awe, along with a deep sense of guilt that, while he was so often away from home, she somehow managed to be simultaneously a homemaker, a mother of three—then four—little girls, as well as his busy secretary and telephone answering service. He made it practically a fetish never to stop without immediately telephoning his Betty, saying candidly, “If my work won’t let me be there, at least she can always know where I am.”

I’m fascinated by the similarities between Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that I observed. For instance, neither could have been much less concerned about acquiring material possessions, and both were obsessed with their work but felt guilty about being away from their families.

Vividly I remember Dr. King recalling among his hardest moments the feeling of mingled anger and shame he had when he and Mrs. King had to explain to their small daughter, Yolanda, that a radio ad for an event she wanted to attend was not meant for their race. Equally vividly I remember Malcolm’s sadness one night when he had overlooked buying a present for his daughter, Attallah, for her fourth birthday—and how he beamed when I surprised him with my intended gift, a black walking doll, and insisted that it be his gift instead.

The two men, who pursued their widely variant philosophies (toward the same goal, I believe), met only once, briefly, with photographers recording their smiles and handshake during the 1963 March on Washington—and I smile, remembering the keen private concern each had for the other’s opinion of him. I was in the midst of interviewing Malcolm for the book when I traveled to Atlanta to interview Dr. King for Playboy magazine. His ever pressured schedule meant I had to make several visits. Dr. King would always let maybe an hour pass before he’d casually ask, “By the way, what’s Brother Malcolm saying about me these days?” I’d give some discreetly vague response, and then back in New York, I’d hear from Malcolm, “All right, tell me what he said about me!” to which I’d also give a vague reply. I’m convinced that privately the two men felt mutual admiration and respect. And I’ve surely no question that they would be pleased to no end to know that their daughters, Yolanda and Attallah, today are friends who work closely together in a theater group.

Attallah is the oldest of the quartet of daughters Malcolm and Betty had by late January 1965, and Malcolm, proud as a peacock that his Betty was yet again pregnant, yet again exulted, “That’s that boy!”—one he wished for. But then, as fate chose to play its hand, seven months after Malcolm’s interment in the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York, the widowed Betty Shabazz bore twin girls—whom she named Malaak and Malikah.

The young widow was caught up in a situation that bore graphic similarity to Malcolm’s mother’s circumstances some thirty years earlier. With six small children—and with her dynamic, outspoken controversial husband brutally murdered—Betty Shabazz, a trained nurse, set out to train and provide for those children in the very best way she could. Attallah, who was then six, remembers, “Our mother kept our home strictly private, and she kept a very low profile, which immensely helped us. We knew she was grieving and that she was working very hard—we were just too little to realize how much of either.”

Actress Ruby Dee, with colleagues and friends, raised funds to aid in the down payment on a home for Betty and the children in Mount Vernon, New York. (Later, when my book Roots made it possible, I signed over to Betty Shabazz my half of the royalties on the Autobiography.) Betty and Malcolm had been determined that the girls receive an excellent education, so Betty worked to increase her own earning power by enrolling at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, to which she commuted. She won her Ph.D. with honors and later joined the faculty of Medgar Evers College of the City of the University of New York, where today she is director of institutional advancement. Through eighteen years of scrimping, sacrificing, counseling and mothering, she has raised the six daughters to be active young women, who are now pursuing a wide variety of careers.

Of the twins, aged seventeen, Malaak is a college biochemistry major, while Malikah studies architecture. At another college, an apartment is shared by Gamilah, nineteen, studying theater arts, and Ilyasah, twenty-one, majoring in biology. Qubilah, twenty-two, has lived in Paris for four years, studying and working as a journalist. And Attallah, twenty-four, does two hundred-odd theatrical performances annually with her and Yolanda King’s group, Nucleus, as well as consultant work in hair care and makeup and clothes designing for private clients.

Of the daughters only Attallah has any memory of her famed father. “Ilyasah can’t remember how, when our father telephoned our mother to say he was coming home, she’d always go and sit by the door to wait,” says Attallah. “And then he’d put all four of us up on his two big knees and just talk and talk to us and laugh a lot. I remember just his presence was so very calming for us kids.”

Malcolm X started me writing books, for which I am most grateful, and from the early days of working with him, I have tried to approach his degree of self-discipline. Looking back, I feel that Malcolm eminently succeeded in achieving a private goal that he once expressed to me: he believed that somehow, every day, he must demonstrate that only a defiant courage could break the fetters still impeding his beloved black people. ~ Alex Haley.

(Alex Haley Remembers is presented under the Creative Commons License. It first appeared in Essence in November 1983 and again in Malcolm X As They Knew Him. © 1983 Essence Communications Inc. © 1992 David Gallen. All Rights Reserved.)