(In The Pacific by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1944 issue of U.S. Coast Guard Magazine.)

(In The Pacific by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1944 issue of U.S. Coast Guard Magazine.)

Alex Haley signed up for a three-year enlistment in the U.S. Coast Guard on 24 May 1939. He started as a Mess Attendant Third Class, since the Mess Attendant and Steward’s Mate ratings were the only ratings in the Navy and Coast Guard open to minorities at that time. Haley was assigned to the cutter Mendota based out of Norfolk where he learned his new job through “on the job” training from the Mendota’s veterans.

During the long patrols Haley began writing letters to friends and relatives, sometimes sending over 40 a week. He received back almost as many letters sent out and soon found himself fielding offers from his fellow crewmen to help them with their letters. Some even offered a financial compensation to lure Haley into composing convincing love letters to the objects of their affections. Apparently his ghostwriting was successful and Haley earned a goodly sum for his off-duty writing.

Haley began writing in earnest and sent short articles off to magazine publishers. On 21 February 1940, Haley was transferred to the cutter Pamlico, which was ported in New Bern, North Carolina. The Pamlico sailed the shallow waters of coastal North Carolina and continued to serve in those waters after the United States entered World War II. On 26 March 1942, Haley was promoted to Officer’s Steward, Third Class.

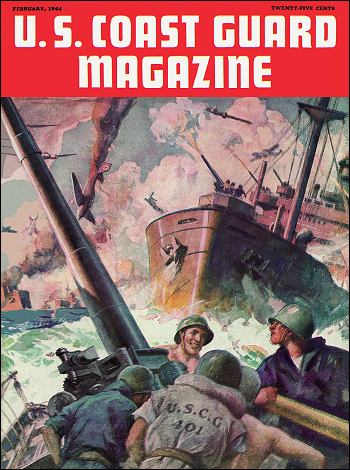

On 7 May 1943, Haley was transferred to the USS Murzim (AK - 95) which saw service in the Pacific Theatre. Duty on board was extremely hazardous and Haley soon began writing what combat was like. The Coast Guard Magazine published his article In the Pacific in their February 1944 issue. In the article Haley describes life on board Murzim as she crossed the Pacific, steaming towards another invasion—and what it was like to undergo yet another call to “General Quarters.”

In The Pacific

WE GOT underway this afternoon …. it’s really a big convoy and, as dusk falls, fascinating to watch the destroyers and DE boats scouring the sea ahead, flanking and behind us. We know that we’re going to (censored) where anything can happen at a moment’s notice and we know most of all that we’ve a cargo, tons and tons of it, that’ll send us all to High Heaven if anything should hit us. So you don’t feel too good—but you don’t show it. You just try not to think about that.

Blackout time …. you’re at the rail watching the other ship’s lights flicker out, one by one. The night closes in a little more, making them shapeless blobs against a background of ocean. You get a last glimpse of the escort vessels—feel good because they’re there.

Comes absolute darkness—you’re glad of that, too …. the enemy can’t see you any better than you can him, so you go below to sack in. Before you do, though, you make sure that your shoes are where you can step into them without even looking. Some don’t even take them off. Then, that done, you go to sleep.

And eventually, you’ll dream, maybe. Forget it all …. you ride a magic carpet that takes you back home (it always does), through a winding valley with lots of green grass, with the “right one” on your arm or maybe in your arms …. it’ll be nice and cool, and worldly things won’t matter.

COMES THE ALARM

“Br-r-r-r-r …. ” (There is really no way on earth to actually describe how it sounds but there it is) General Alarm!

You jump out of the winding palley and into your shoes and in the same motion grab for your lifejacket—it was your pillow if you didn’t sleep in it—and dash up the ladder trying like hell to keep from dropping your gas mask while you jerk the jacket on. The loudspeaker’s booming something—you just get snatches of it, “ ….. submarine ….. port side ….. ” “ …. Lookouts, keep sharp watch for torpedo tracks …. ”

You’re at your station then, opening your eyes wide to try and get accustomed to the darkness as quickly as possible. You don’t see anything …. hope to hell you don’t ever. Two things you hear—the beat of the engine as she strains for extra knots and the beat of your heart …. while you strain for composure.

Fifteen minutes pass …. Good Lord, won’t something happen …. just anything …. Thirty minutes …. you’re sweating, cold sweat and somewhere, from a long far-distant world you remember the little prayer Mom used to teach you when you knelt at her knees …. “Now I lay me down to sleep …. pray the Lord my soul to keep …. ” Then your mind slips on down into the holds where tons of sudden death slumber. You just wish for action now because you know that once it comes, you’ll be too busy to think about being scared …. thirty-five minutes …. Please, Jap, please come out and fight ….

“All hands secure from general quarters!”

“Thank God for a loudspeaker …. it just took two tons off my shoulders.

…. So you go back below. Maybe the sub was there and decided not to take the chance …. maybe there wasn’t any sub at all. You don’t know which but you don’t give a damn either so long as nothing happened. After a while you go to sleep again, but you don’t usually dream anymore.

Morning comes and you’ve all but forgotten it. After all, it was just another night.

And that, dear people back home, is strictly fact—straight from experience.

But we don’t kick—too much. Sometimes, homesickness gets us down and things seem sort of dismal for awhile, especially when you go the same places over and over again for months on end and life becomes a ritual. Most times though, we invent things to keep us from getting in the dumps—bull sessions, whittling, knot-tying—you’d be surprised at the things we find to do.

In the meantime, we’ll go on making the boys over here recognize that the Coast Guard is really on the job.

(In The Pacific by Alex Haley is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the February 1944 issue of U.S. Coast Guard Magazine. © 1949 U.S. Coast Guard. All Rights Reserved.)