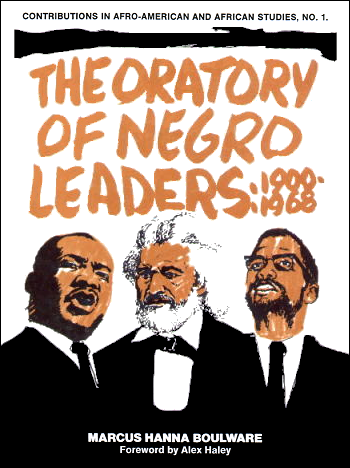

The Oratory Of Negro Leaders: 1900-1968

The Oratory Of Negro Leaders: 1900-1968(Contributions In Afro-American And African Studies)(Marcus Hanna Boulware, Alex Haley)

The Oratory Of Negro Leaders: 1900-1968 examines the personal and professional lives of famous black orators of the twentieth century.

“Many years ago I was invited to deliver a short speech during Negro History Week sponsored by a local historical society. The assigned topic was ‘Spokesmen for an Oppressed People.’ To secure materials for this address, I went to the local library to assemble a bibliography. Surprisingly, there was only one anthology—Negro Orators and Their Orations by Carter G. Woodson, the noted historian. While this book was inadequate, it supplied the bulk of materials for the address…

“The paucity of materials on Negro oratory in histories revealed a need for a hook of this kind. Hence, I prepared this history, which has been limited to the twentieth century. It will tell the story of Negro oratory in the United States from the rise of Booker T. Washington in 1900, as a finished public speaker, through June, 1968, of the Great Society made popular by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Considerable emphasis will he placed upon the Negro revolt which has been symbolized in the leadership of the orator, Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as through the civil-rights activities of college students who affiliated themselves with Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

“This volume is the first history of Negro oratory in the United States during the twentieth century. I am very much aware that I must assume full responsibility for the contents of this book. It is hoped that the information in this work will influence the reader to conclude that effective public speaking is one of the gateways to leadership.” ~ Marcus H. Boulware – (Excerpted from his Preface)

Alex Haley contributed to this work by writing the following foreword:

Foreword By Alex Haley

There are three reasons why I am intrigued by a book on “black oratory.” Black orators were major boyhood heroes of mine; they were 1930s southern black preachers. Secondly, as something of a black historian myself, I am perhaps more aware than most people of how, in this country in the last century, one or another form of black oratory has been the keel of the black experience. Thirdly, in very recent years, it has been my privilege to interview in depth, to hear and see repeatedly, the two men whose spell-binding abilities unquestionably place them first among the modern-era black orators whom Professor Boulware includes: the late Dr. Martin Luther King, of whom I wrote an in-depth magazine portrait; and the late Malcolm X, with whom I spent two years in collaboration writing The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

This book is needed not only by students of rhetoric and oratory, but also by students of history. The latter in particular will find satisfaction in the wide sampling, sensitively selected, that Professor Boulware offers here. The reader will become acquainted not only with the black preachers and politicians, but with statesmen, scholars, and demagogues, both the saints and the sinners.

This book, too, will give its readers more insight into why and how the history of American blacks has witnessed a progression from the sheer survival attitudes of most slaves to the growing present black attitude either to assimilate fully in American society or, at least psychologically, to reject and separate from it.

The white perspective toward black voices has undergone almost as vast a change. In the past, those few whites who were exposed to any black oratory at all appraised it, generally, as an amusement—with rare exceptions, such as, of course, Booker T. Washington, Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois, and a handful of others, who came to be limelight figures for whites. At best, whites considered black oratory to be a curiosity, very much as if some few simians had been trained remarkably. This is well put by my friend and colleague here at Hamilton College, Professor Charles Todd: “The black orator was regarded by most white men as someone who had accidentally stumbled onto a clever parlor trick. Today, however, the white man is no longer amused.”

The amusement ceased at about the time of the Malcolm X stance of “I’m Talking To You, White Man!”, along with the development of Dr. Martin Luther King’s forthright brand of nonviolence.

So, while whites laughed at black orators for being largely illiterate or poorly trained, ironically one reason why those black speakers played such a strong role in black history is something which history itself has proved most amply: that great orators need not be educated. In fact, traditionally oratory has been a natural gift among even the most unliterate peoples.

Says Carter G. Woodson, in Negro Orators And Their Orations, a volume that preceded Professor Boulware’s work: “Oratory in the broad sense requires no other equipment than fluency of speech and self-confidence.” Massachusetts Senator George F. Hoar, himself a powerful orator of the 1890s, said, “The orator must be able to play at will on the mighty organ, his audience, of which human souls are keys.”

The really special value of Professor Boulware’s book lies in the fact that it gives us, as a corrective, a wide range of sundry types of black orators, of both the past and the relative present. These untutored earlier black orators were not merely articulate beings; they were physically and psychically one with their audiences. In their own everyday lives they shared fully their audiences’ trials and despairs. They emerged from among their people to provide a motivation for further endurance and sustained hope.

When we speak of the earliest black orators, we must begin with the black preachers whose model and precedent has spawned virtually all other facets of black oratory. The black preachers, Sunday after Sunday, brought new life to their tired people. They graphically presented promise and deliverance. “Their tones were beautiful, their gestures natural,” says Woodson. “They could suit the word to the action, and the action to the word. Using skillfully the eye and voice, they reached the souls of man.”

For a true appreciation of the early black orators one actually had to see and hear them, as I did as a boy. For only thus could one savor the sheer flavor and charisma of these elocutionary artists. Yea! Those who, thundering from their pulpits, would part the Rea Sea or stir the Eagle’s Nest! Perhaps their apex was reached with that black preacher whom the great black poet James Weldon Johnson has described: “—so sure of his power . . . that banging shut his Bible and jerking off his glasses, and glaring at his parishioners, who had come to feel his confidence that particular Sunday morning, he announced ‘This mornin’, Brothers and Sisters, I ‘tends to ‘splain the inexplainable, to fin’ the indefinable, to unscrew the inscrutable!’ ”

I can hear them now out there in those worn pews, “Yay man, brother!” And how I wish I might have been in that church that morning! For hasn’t it been said that not only should the orator instruct, but he should move, and he should delight? Did not Cicero say, “The object of oratory alone is not truth, but it is persuasion”? And Marlowe: “The heart must glow before the tongue can gild”?

My point is that this preacher whom Johnson describes—in fact, all of those largely untutored historical black voices—fueled, with their raw eloquence, the hopeful emotions of black men down through their long history in this country. What were they engaged in if not pure art, giving their people more by far than all of the known “-ologies” gave them, more than all of the rest of the society in which they lived gave them? For, the point is, their black listeners believed—and they did find endurance and hope!

Few will deny that black Christianity has been more fervently articulate in America than white Christianity has been—due in part to the patterns of exultant audience feedback that history’s unheralded black preachers sought and demanded of their congregations. Dr. Martin Luther King, standing before three hundred thousand people drawn to the March on Washington, echoed that earlier sound in his “I Have a Dream” speech. It was a more polished performance than was ever achieved by his predecessors; nonetheless, it brought back memories of all black yesterdays, and the black dreams that filled and buoyed them. From the slave orators to Dr. King and Malcolm X, and on into the present shifting hierarchy of articulate black militants, only the words and phrases have differed, dictated by the social forces of the changing times. But through it all runs one central theme: the black man petitioning for human rights.

Professor Boulware here offers us a wider range of oratory and orators than have hitherto been recognized. Naturally, he has not included all of my particular favorites—among them Richmond, Virginia’s Reverend (“De Sun Do Move”) John M. Jasper, of post-Civil War fame, along with Mississippi’s Senator Blanche K. Bruce (1841-1898). But all this says is that the anthologist will never live who will not omit some of his readers’ favorites. Professor Boulware’s feat, to me, is that his sensitive selection has made available to us so many of them.

This is a splendid beginning to the critical search we must conduct into all facets of black life and history in America. We have been given here a much-needed book, an important book, and one that richly deserves to be used widely. ~ Alex Haley, July, 1969.

(The above foreword by Alex Haley is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. The Oratory Of Negro Leaders: 1900-1968 was authored by Marcus Hanna Boulware. © 1969 Negro Universities Press. All Rights Reserved.)