(I’m Talking To You, White Man was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on September 12, 1964.)

(I’m Talking To You, White Man was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on September 12, 1964.)

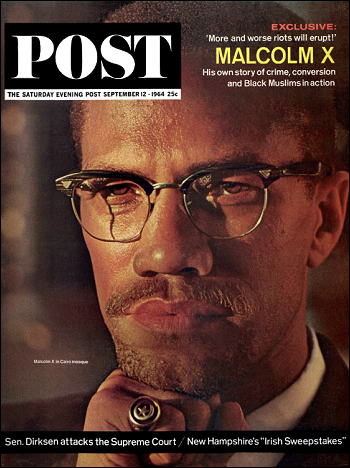

On September 12, 1964, the cover of The Saturday Evening Post showed the face of Malcolm X—the radical leader who promoted black power and armed resistance to the status quo.

Playboy magazine had earlier introduced us to Malcolm X through a featured interview conducted by Alex Haley (Malcolm X’s biographer) in May of 1963 entitled A Candid Conversation With The Militant Major-Domo of The Black Muslims.

Haley first hears about the Nation of Islam in San Francisco in 1959, and first meets Malcolm X in New York in 1960. He writes a few articles on Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad—Mr. Muhammad Speaks for Reader’s Digest in March 1960 and Black Merchants of Hate for The Saturday Evening Post on January 26, 1963—before a publisher proposes to Haley the idea of a biography. Having won the trust of Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad, Haley gets them to agree to the project.

This Saturday Evening Post issue enlightened the masses with a fourteen-page excerpt from The Autobiography of Malcolm X in September 1964, a large story opening with a full-page color illustration of Malcolm X praying in the great Mosque of Mohammed Ali in Cairo.

This story presents an autobiography of Malcolm X, an African American Muslim rebel who defies both white and African American leadership. His family background; His views on violence and racism in the U.S.; His inclination toward Islam; Moral code of discipline in Islam; His plans to form a mosque in New York City known as the Muslim Mosque Inc., as the working base for an action program designed to eliminate the social degradation suffered daily by African Americans.

I’m Talking To You, White Man

The explosive Black Muslim rebel who defies both white and Negro leadership

tells a story that swings from violence and degradation to religion and racism.

When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of Ku Klux Klan riders came suddenly one night, galloping on their horses around our home in Omaha, Nebr. They stopped with their upraised torches lighting all around the house to prevent any escape by my father. My mother came out of the front door. She defied them that she was alone with her three small children, and that my father was away, preaching, in Milwaukee. The Klansmen shouted threats and warnings at her that we had better get out of Omaha because the good Christian white people were not going to stand for my father’s “spreading trouble” among the local “good” Negroes with the “Back To Africa” teachings of Marcus Garvey—at that time, 1925, the most controversial black man on earth.

The Klansmen spurred their horses and galloped about the house, close enough to use their gun butts to shatter all of the glass panes in the windows. Then they rode away. My father, the Rev. Earl Little, was enraged when he returned. He decided that they would wait until I was born—which would be soon—and then the family would move. I am not sure why he made this decision as he was not a frightened Negro, as most then were, and still are today. My father was a big, six-foot-four, very black man. He had only one eye. How he had lost the other one, I never have known. He was from Reynolds, Ga., where he had finished the third or maybe the fourth grade. Among himself and his six brothers he had seen four of them die of violence, three of them in the South, killed by white people, including one of them hung. What my father could not know was that of the three remaining, including himself, only one, my Uncle Jim, would die in bed, of illness. Northern white police were later going to shoot my Uncle Oscar, and my father was finally, too, going to die at white hands.

It has always stayed on my mind that I would die by violence. I have done all that I can to be prepared.

I was my father’s seventh child. He had by a previous marriage three, Ella, Earl and Mary, who lived in Boston. In Philadelphia he had met and married my mother. Their first child, my oldest full brother, Wilfred, was born there. They moved from Philadelphia to Omaha, where Hilda and then Philbert were born, and then I was the next one in line.

The family waited, as my father had decided, and my mother was 28 when I was born on May 19, 1925, in an Omaha hospital. Louise Little, my mother, who was born in Grenada, in the British West Indies, looked like a white woman. Her father was white. She had black hair, and her accent did not sound like a Negro’s. Of this white devil father of hers, I know nothing except her shame about it; I remember hearing her say that she was glad that she never had seen him. It was of course as a result of him that I got my reddish-brown “mariny” color of skin, and my hair of the same color. I grew up as the lightest child in our house. (Out in the world later on, in Boston and New York, I was for years insane enough to feel that it was some kind of status symbol to be light complexioned. Now, I hate every drop of that white rapist’s blood that is in me.)

We next went to Lansing, Mich. A house was bought, and soon my father was doing free-lance Christian Baptist preaching in local Negro churches, and during the week he was moving about, spreading the Garvey teachings. He had begun laying the foundation for the store that he had always wanted to own when, as always, some stupid local “Uncle Tom” Negroes began funneling everything they heard to the local white people.

On the nightmare 1929 night which is the earliest vivid memory that I have, I remember being suddenly snatched awake into a nearly petrifying confusion of pistol shots and shouting and smoke and flames. My father had seen and shouted and shot at the two white men who had set fire to our house and were running away. My mother with the baby in her arms just made it into the yard before the house crashed in, showering up sparks. The police and firemen came and stood around watching the house burn the rest of the way.

I remember waking up in 1931, again to the sound of my mother’s screaming. When I scrambled out, I saw the police in the living room. All of us children who were staring knew that something bad had happened to our father.

My mother said later that she was taken by the police to the hospital, and to a room where a sheet was over my father in a bed, and she wouldn’t look, she was afraid to. Probably it was wise that she didn’t. My father’s skull, on one side, was crushed in. He had been bludgeoned with something. And his body was cut almost in half where he had been run over by the wheels of a streetcar. He had been bludgeoned by someone, and then laid across the tracks for the streetcar to run over. He lived two-and-a-half hours in that condition. (Negroes born in Georgia had to be strong just to survive.) It was morning when we children at home got the word that he was dead. I was six.

My mother was 34 years old now. She was very shook up. Some kind of a family routine got going again. And for as long as the first insurance money lasted, we did all right. When the state welfare people began coming to our house, we would come home from school sometimes and find them there talking with our mother, asking a thousand questions. They were acting and looking at her and us and around in our house in a way that had about it the feeling that we were not people. We were just things, that was all.

We swiftly began to go downhill. The physical downhill wasn’t as quick as the psychic. My mother was, above everything else, a proud woman, and it took its toll on her that she was accepting charity. And her feelings communicated to us, and among us children. It didn’t help any when I began to get caught stealing snacks from stores, and the welfare people began to focus on me.

It was about this time that the large, dark man from Lansing began visiting. He looked something like my father. He was single, and my mother was a woman without a man, and the state people were bugging her. The man was independent; she would have admired that. She was having a hard time with disciplining us and a big man’s presence alone would help. And if she had a man to provide, it would erase the state people in general.

It went on for about a year, I guess. And then the man from Lansing jilted my mother suddenly. It was a terrible shock to her. It was the beginning of the end of reality for my mother. She began to sit around, or walk around, and talk to herself, almost as if she was unaware that we were right around there in the house, watching her. It was gradually terrifying.

The state people saw her weakening. That was when they began the definite steps to take me away from the house. They began to tell me how nice it was going to be at the nearby Gohannes’s home, where the Gohannes’s and their nephew, “Big Boy,” and old Mrs. Adcock all had said how much they would like to have me live with them.

When finally I did go to the Gohannes’s home, at least in a surface way I was glad. I would return home to visit fairly often, and saw how the state people were making plans to take over all the children. My mother talked to herself nearly all the time now. The court orders were signed, finally. They took her to the state mental hospital at Kalamazoo. My mother is still in the same hospital.

I guess I must have had some vague idea that if I weren’t in school, I’d be allowed to just live at the Gohannes’s and wander around town, stealing and loafing, or maybe get a job if I wanted one. But I got rocked on my heels when a state man that I hadn’t seen before came and got me at the Gohannes’s and took me down to court. They said I was going to the detention home. It was about 12 miles from Lansing, in Mason, Mich. I was 13 years old. The detention home was where all boys and girls on their way to reform school were held, waiting.

The lady in charge of the detention home, Mrs. Swerlin, and her husband were very good people. Her first name was Lois, and Mr. Swerlin’s was Jim, I remember. She was bigger than he, a big, buxom woman. She showed me to my room—in my life, my first own room. It was in one of the dormitorylike buildings where the kids in detention were kept. I discovered next, with surprise, that I ate right at the tables with them.

Different ones of the detention home youngsters, when their dates came up, went on off to the reform school. But mine came up two or three times; it was always ignored. I saw new youngsters arrive and leave. I was glad, and grateful. I knew it was Mrs. Swerlin’s doing. She finally told me one day that I was going to enter the Mason High School.

The white kids there were friendly. Somebody, including the teachers, was calling me “nigger” everywhere I turned, but it was easy to see that they didn’t mean any harm. “The nigger,” in fact, was extremely popular. I was unique, the only one around—you know what I mean? Every Sunday I went to Sunday school and church. There was no black church to go to, so I went to the white one.

In Mason High I was elected the class president! It shocked me. More than it did other people. I see it now. My grades were among the highest in the school. I was unique in my class, like a pink poodle. I am not going to say that I wasn’t proud.

Along toward the end of that year, our father’s grown daughter, Ella, by his first marriage, came from Boston to Lansing. After visiting each home where my different brothers and sisters were staying, Ella left. But she had told me to write to her, and she had suggested that I might like to spend the summer holiday visiting her in Boston. I jumped at that chance.

That summer of 1940 I caught the Greyhound bus, with my cardboard suitcase and wearing my green suit. If someone had hung the sign Hick on me, I couldn’t have looked much more obvious.

Ella met me. She took me home. The house was on Waumbeck Street, in Roxbury, the Harlem of Boston. I saw, or met, I suppose a hundred people whose big-city talk and ways left my mouth hanging open. The cars they drove! I tried to describe it, when I got back to Lansing, but I couldn’t. I thought constantly about all that I had seen.

One day Mrs. Swerlin called me into the living room. She said she felt there was no need for me to be at the detention home any longer. I wrote to Ella in Boston. I don’t know how Ella did it, but official custody of me was transferred from Michigan to Massachusetts. The same week that I finished the eighth grade, I again caught the Greyhound bus. All praise is due to Allah! If I hadn’t gone on to Boston, probably I’d still be a brainwashed black Christian.

This time I was big enough to walk around town by myself, and I just knocked myself out, gawking. Boston’s downtown had the biggest stores that I ever saw, and white people’s restaurants and hotels. On Massachusetts Avenue, next door to the Loew’s State Theater, was the big, exciting Roseland State Ballroom. Big posters advertised the nationally famous bands, white and Negro, that had been there. I saw that Coming Next Week was Glenn Miller.

I wanted to find myself a Job to surprise Ella, to show her I could, mostly. One afternoon something told me to go inside a poolroom whose window I was looking through. Something made me decide to talk to a stubby, dark fellow who racked up the balls for the pool players, and whom I’d heard different ones call “Shorty.” And one day he came outside and saw me standing there with my kinky, reddish hair and he had said, “Hi, Red.” so that made me figure that he was friendly. Inconspicuously as I could, I went on to the back, where this Shorty looked up at me over an aluminum can that he was filling with the powder that pool players sprinkle over their fingers. His hair had been “conked” to make it slick and straight. I told him I’d appreciate it if he’d tell me how could somebody go about getting a job. He asked what had I ever done, and where. And that was how he learned that I’d been at Mason High. He nearly dropped the powder can. He hollered “My homeboy! Man, gimme some skin! Man, I’m from Lansing!” Pretty soon we sounded as though we had been raised in the same block, and we were reacting like long-lost brothers. “You’re my homeboy—I’m going to school you to the happenings.” I just had to stand up there and grin like a fool, I was so glad to hear those words.

I hung around in the back of the poolroom, and Shorty, keeping an eye on the pool games up at the tables, would run and rack balls, then come back and talk. He asked my circumstances, and I told him about Ella and all. Shorty’s job—or “slave”—in the poolroom there, he said, was just to keep ends together while he learned his horn, A couple of years before he’d hit the numbers, and bought a saxophone. “Like all the cats,” he told me, “I play at least a dollar a day on the full number with my main man. Soon as I hit that, I plan to organize my band, get the studs some uniforms and stuff.” Before we went out he opened his saxophone case and showed the horn to me. It was gleaming brass against the green velvet, an alto sax. He said, “Keep cool, homeboy. Some of the cats will turn you up a slave.”

When I got home, Ella said there had been a telephone call from somebody named Shorty. He had left a message that over at the Roseland State Ballroom, the shoeshine boy, named Freddie, was quitting that night, and Shorty had told him to hold the job for me.

The front of the ballroom was all lighted when I got there. A man at the front door was letting in members of Benny Goodman’s hand. I told him I wanted to see the shoeshine boy, Freddie.

A wiry, brown-skinned, “conked” cat upstairs in the men’s room greeted me. “You Shorty’s homeboy?” I said I was, and he said he was a friend of Shorty’s. “Good old boy,” Freddie said. “He called me, he’d just heard I hit the big number, and he figured right I’d be quitting.” Then he gave a demonstration in how to make the shine rag pop like a firecracker. By the close of the dance Freddie had let me shine the shoes of three or four stray drunks he talked into it, and I had practiced picking up my speed on his shoes until they looked like mirrors. After we had helped the janitors to clean up the ballroom after the dance, throwing out empty liquor bottles we found, stuff like that, Freddie was nice enough to drive me all the way home to Ella’s on the “hill” in his maroon, second-hand Buick. He looked across at me. “Some hustles, now, you just got to realize you’re too new for. Some cats will ask you for liquor, some more for a ‘stick’—reefers. Whatever else they ask you for, you just act dumb, until you get able to dig who’s a cop. You can make ten, twelve dollars a dance for yourself if you work everything right. The main thing you got to remember is that everything in the world is a hustle. OK, Red?”

In about two weeks I had found out that Freddie had done less shoeshining and towel hustling than selling liquor and reefers, and contacting white “Johns” for some Negro girls. Most of the Roseland’s dances were those for whites only, and they had white bands only. The Negro dances with Negro bands were only now and then. They jam-packed that ballroom, the black chicks in real way-out silk and satin dresses and shoes, and their hair done in all kinds of styles, and the cats sharp in their “zoot” suits and crazy “conks,” and everybody grinning and greased and gassed.

The first liquor I drank, my first cigarettes, even the first marijuana—reefers—I can’t specifically remember. But I know they all mixed together with my first shooting craps, playing cards, and betting my dollar a day on the numbers as I started some light hanging out at night with Shorty and different ones of his friends, and, sometimes, chicks they knew. Mixed in with this time, too, was my first zoot suit and my first processing of my kinky hair to straighten it, the conk. Shorty had promised to school me in how most young cats beat the barbershops’ three- and four-dollar price by making their own “congolene,” and conking themselves, once they learned how.

The evening that Shorty said that we would do it at his pad, alter he got off from the poolroom, I took the little list he had printed out for me, and went to a grocery store. I got there a can of Red Devil lye, two eggs, and two medium-sized white potatoes. Then, at a drugstore near the poolroom, I asked for Vaseline; a large jar; a large jar of soap; a big comb and a fine comb; one of those rubber hoses with a metal spray head, and a rubber apron and a pair of glove.

Shorty paid six dollars a week for a room in his cousin’s beat-up apartment. He peeled the potatoes and thin-sliced them down into a quart Mason fruit jar. He started stirring with a wooden spoon down among the potato slices as he gradually poured in a little over a half can of the lye. A jellylike, starchy-looking stuff resulted from the lye and potatoes, and Shorty broke in the two eggs, stirring in real fast. The congolene turned pale-yellowish. “Feel the jar,” Shorty said. I cupped my hand against the outside, and snatched it away. “Damn right, it’s hot, that’s that lye,” Shorty said. “So you know it’s going to burn when I comb it in—it burns bad. But the longer you can stand it, the straighter the hair.”

He made me sit down, and he tightly tied the string of the new rubber apron around my neck, and combed up my bush of hair. From the big Vaseline jar he took fingersful and massaged, hard, all through my hair and onto the scalp. He thickly Vaselined my neck, ears and forehead. “When I get to washing out your head, you got to remember that any congolene left in burns a sore.”

The congolene just felt warm when Shorty started combing it in. Then, my head set afire! I gritted my teeth and tried to pull the kitchen table’s sides together. The comb felt like it was raking skin off! I couldn’t stand it any longer; I bolted to the wash basin. I was cursing Shorty for everything I could think of when he got the spray going and started soap-lathering my head. “The first time’s always worst. You get used to it better. You took it real good, homeboy. You got a good conk.”

When Shorty let me stand up and see in the mirror, my scalp still flamed, but this time not as bad; I could bear it. The mirror reflected Shorty behind me. We both were grinning and sweating. After that Vaseline, I had this thick, smooth sheen of shining red hair—real red—and straight as any white man’s!

Shorty would take me to groovy, frantic scenes (parties) in different chicks’ and cats’ pads. With the lights and the jukebox down mellow, we “blew gage” (smoked marijuana) or “juiced back” (drank liquor). The chicks I met were fine as May wine, the cats were hip to all happenings. (That’s just to give a taste of the slang that was talked by everyone whom I respected in those days.) I’d acquired the fashionable ghetto adornments, my zoot suits and a conk; I had begun drinking liquor, smoking cigarettes and reefers, and I was absorbing a lot of the “hip” dialogue.

Beacon Hill Chick

I had to quit the shoeshine hustle because I liked to be on the Roseland dance floor when the bands were playing, but Ella helped me get a job as a soda jerk in the Townsend Drug Store, two blocks from her house. That was when I met my first white woman. I’m going to call her Sophia, for which I have my own private reasons. I met her at the Roseland Ballroom. When I caught this fine blonde’s eyes, I just stopped. Froze! This one I’d never seen among the white girls that came to the Roseland black dances. She was giving me that “I-go-for-you” look.

She didn’t dance well, at least not by Negro standards. But who cared? I could feel the staring eyes of other couples around us. We talked. I told her she was a good dancer, and asked her where she’d learned. I was trying to find out why she was there. Most white women who came to the black dances, I knew their reasons, but you didn’t see her kind. She had vague answers for everything. And then I know she asked in that cool Lauren Bacall sound of hers would I like to go for a drive.

I just couldn’t believe my luck. Would I? It was just too much!

For the next five years—into 1946, when I went to prison—Sophia was my main white woman. For two of the years she stayed single; for the other three she was married to a white man, for convenience, I soon found out from her, different parts of it at different times, that she was the oldest of a well-off divorced Boston woman’s three daughters. Sophia would pick me up. I took her to the dances, but mostly to the bars around Roxbury. We drove all over. Sometimes it would be nearly daylight when she let me out in front of Ella’s.

She was entranced with me. Automatically, I began to see less of Shorty. When I did see him and the gang, he would gibe, “Man, I had to comb the burrs out of homeboy’s head; now, looka here, he’s got a Beacon Hill chick.”

Meanwhile I left the drugstore and soon found me a new job. I was a busboy at the Parker House. After only a few weeks, one Sunday morning I ran in to work expecting to get fired, I was so late. But the whole kitchen crew was too excited and upset to notice. I picked up their talk—Japanese planes had just bombed somewhere called Pearl Harbor.

You wouldn’t have believed it was me. “Getcha goooood haaaaaman’ cheeeeeese . . . sandwiches! Coffee! Candy! Cake! Ice cream!” Rocking along the tracks every other day for four hours between Boston and New York, in the coach-car aisles of the New Haven line’s Yankee Clipper. An old Pullman porter, a friend of Ella’s, had recommended the railroad job for me. He had told her that the war was snatching away railroad men so fast that if I could pass for 21, he could get me on. I knew that several New Haven trains ran between Boston and New York. Secretly, for years, I had wanted to visit New York City. Right there since I had been in Roxbury, I had heard so much raving about “The Big Apple,” as it was called, by various kinds of people who traveled a lot, by musicians, merchant-marine sailors, chauffeurs for white families, salesmen and different hustlers.

Anyway, at the railroad-personnel hiring office down on Dover Street, a tired-acting, grayheaded, old white clerk got down to the crucial point, “Age?” When I told him “Twenty-one,” he never lifted his eyes up from his pencil. And I knew I had it made.

The dining-car crew told me before we left Boston that their favorite spot in New York was a place called Small’s Paradise. The cooks took me up to Harlem with them, in a cab. White New York passed by like a scenario, then almost abruptly, when we left Central Park at the upper end, at 110th Street, the people’s complexion changed to Negroes. It was about five-thirty in the afternoon.

Busy Seventh Avenue ran along in front of Small’s Paradise, No Negro place of business had ever impressed me so much. Around the big, luxurious-looking circular bar probably were 30 or 40 men, or mostly men, and several women, drinking and talking.

From then on, every layover night in Harlem, I explored new places. I first got a room at the Harlem YMCA because it was less than a block from Small’s Paradise. Then I got a room, cheaper, at a rooming house where most of the railroad men stayed. I hung in Small’s and the Braddock bar so much that the bartenders began to pour bourbon, my favorite brand of it, when they saw me. And the steady customers in both places, the hustlers in Small’s and the musicians and entertainers in the Braddock, began to call me “Red,” the nickname that my red conk made natural, I know.

My musical friends were of the caliber of Duke Ellington’s great drummer, Sonny Greer, and that great personality with the violin, Ray Nance. Ray’s the one who sang that wild “scat” style, that “bloo-blop-ble-blop-bla-bloo-blam-blam—” Remember that? And people like Cootie Williams; a little later on Pearl Bailey sang with Cootie. And Eddie (Mr. Cleanhead) Vinson; in the Braddock he’d kid me about his conk—he had nothing up there but skin. He was hitting the heights then with his Hey, Pretty Mamma, Chunk Me in Your Big Brass Bed. I knew Cy Oliver; he was married to a kind of red girl, and they lived up on “Sugar Hill.” and he did a lot of arranging for Tommy Dorsey.

By that time, on the Yankee Clipper, they had a laughing bet going among the waiters that I wasn’t going to last. Because I had so rapidly become such a wild young Negro. I’d come to work, loud and wild and half high off either liquor or reefers, and I’d stay that way, jamming sandwiches at people until we got to New York. Off the train I’d go through that Grand Central Station afternoon rush-hour crowd, and many people simply stopped in their tracks to watch me pass. The drape and the cut of a zoot suit showed to the best advantage if you were tall, remember—and I was over six feet. My conk was fire-red. My knob-toed, orange-colored “kickup” shoes were the Cadillacs of shoes in those days. (They made these ridiculous styles for sale only in the black ghettos where ignorant Negroes like me would pay the big-name price.) And then, between Small’s Paradise, the Braddock Hotel, and other places, as much us my $20 or $25 would let me, with my increasing number or friends I drank liquor, smoked marijuana, and got a few hours’ sleep before the Yankee Clipper rolled again.

What did me in was that when some passenger wrote the New Haven line a mad letter, the conductors backed it up, telling how many verbal complaints they’d had, and how many warnings I’d been given. I didn’t care. Me quitting the railroad was in my mind only a matter of time anyway. And I knew that the way the Army was snatching up anybody who was warm and able to walk, all the jobs I could want were going begging.

Back in New York, stony broke, I went over to Small’s Paradise. One of the bartenders called me aside and said that if I went downstairs right away to the office, I might be able to replace a day waiter who was about to go into the Army.

Ed Small and his brother, Charlie, had seen me in the place so much that it made it pretty easy. They also knew I was a railroad man, which, for a waiter, was the best kind of recommendation. It was in 1942, just past my 17th birthday.

With Small’s practically in the center of everything happening, waiting tables there was Seventh Heaven seven times over! Charlie Small had told me not to be late! Why, what was he talking about? I was so anxious to be there, I’d arrive an hour early! Inside of a week I don’t know who liked me most, the cooks or the bartenders. And the customers, who had seen me among them around the bar, recognizing me now in the waiter’s jacket, were surprised, pleased, and they couldn’t have been more friendly. Recognizing that by New York terms I still was just a hick, they began to school me. Every day I listened raptly to one or several of the customers who felt like talking—these seasoned, mature hustlers—and it all added to my “‘education.” Particularly, my ears absorbed like sponges when some of them in a rare burst of confidence, or a little beyond his usual number of drinks, would tell me “inside” things about the particular form of hustling that he pursued.

Plain-clothes detectives were quietly identified to me, by a nod, a wink. Knowing the law people in the area was elementary for the hustlers, and, like them, in time, I would learn to sense almost the presence of any police and agent types. And added to the civilian ones then in 1942, each of the military services had civilian-dressed “eyes” and “ears.”

Every day, all of my tips—as high as $10 a day—I would gamble on the numbers, and dream of what I would do and buy as soon as I “hit.” The straight number chances of hitting were a thousand-to-one, but your chances could be increased by what was called “combinating.” For example, six cents would put one penny on each of the six possible combinations of three digits. Take the number 840, say. “Combinated,” it would cover 840, 804, 048, 408, 480 and 084.

“Detroit Red”

The daily small army of “runners” each got 10 percent of the money they turned in, along with the bet slips, to their “controllers.” (And if you hit, you gave the runner a 10 percent tip.) A controller might have as many as 50 runners working for him, and the controller got 5 percent of what he turned over to the “bankers,” who paid off the hits, paid off the police, and, off the balance, got rich.

I should stress that Small’s wasn’t any haven for criminals. I dwell upon hustlers because it was their world that fascinated me. Actually, for the night-life crowd, most of which the hustlers regarded as “square,” Small’s was one of the two or three most decorous night spots that Harlem had. It was formally recommended by the New York City Police Department to white people who would ask where was safe to go in Harlem.

From time to time I’d have Sophia come over from Boston to see me. She would come in on a late-afternoon train, and come to Small’s and I’d introduce her around until I got off”. We would make it to the Braddock Hotel bar, where she would nearly have a fit with meeting some of the “name” musicians who now would greet me like an old friend. “Hey, Red—who have we got here?” And they would make on over her. They wouldn’t let me even think about paying for the drinks I ordered.

Once, when I called Sophia in Boston, she sounded funny. She said she couldn’t get away until the following weekend. She told me that she had just married some well-to-do Boston white fellow. He was in the service. She went on to say she didn’t mean for it to change a thing between us. I told her it made me no difference.

When I had been around Harlem long enough to show signs of permanence, it was inevitable that I was going to get a nickname that would identify me beyond any confusion with two other red conked and well-known “Reds” who were around. I had met them both. One was “St. Louis Red.” a professional armed robber. When I was sent to prison, he was doing some time for trying to stick up a dining-car steward on a train between New York and Philadelphia. The other one was “Chicago Red.” In a speakeasy where I was a waiter later on, he was the funniest dishwasher on this earth, and we became good buddies. Now he’s making his living being funny as a nationally known stage and nightclub comedian. (I don’t see any reason why old “Chicago Red” would mind me telling that he is “Redd Foxx.”) Anyway, before long, it happened. Different people, knowing I was from Michigan, would ask me what city. Since most New Yorkers never had heard of hicktown Lansing, I would say “Detroit.” Gradually, I began being called “Detroit Red”—and it spread, and stuck.

One afternoon in early 1943, before the regular six-o’clock Small’s hustling crowd had gathered, this real Georgia-looking black soldier sat drinking at one of my tables by himself. He looked dumb and pitiful, and it was because of that why I did one of the dumbest things I ever did in those years. The next drink that I served this soldier, I bent over close wiping the table, and asked him if he wanted a woman.

I knew better. It wasn’t only Small’s Paradise law, it was every tavern’s law, at least if it wanted to stay in business, not to get involved with anything that could be interpreted as impairing the morals of servicemen, or any kind of hustling off them. Big trouble had been caused by this for dozens of places, some even well-known places had been put off limits by the military, and some even had lost their state or city licenses.

And I had suckered myself right into the hands of one of those military “spies.” Why, this black tool of the white man said he sure would like a woman, so gratefully; he even had a dumb Georgia accent! And I gave him the phone number of one of my best friends among the prostitutes at the rooming house where I lived. I gave the fellow a half hour to have gotten there, and then I telephoned. I expected what the woman said to me, that no one like that had been there.

I didn’t even go back out to the bar. I just went straight to Charlie Small’s office. “I just did something, Charlie,” I said, “I don’t know why I did it—” And I told him what I’d done.

Charlie looked at me. “I wish you hadn’t done that, Red.” We both knew what he meant.

When the West Indian plain-clothes detective, Charlie Barts, came in, I was wailing. When we got to the 135th Street precinct, it was busy with police in uniform. I reflected that two things were in my favor: I’d never given the police any trouble, and when that black spy soldier had tried to tip me, I had waved it away and told him I was just doing him a favor. I saw some other detectives side-mouthing with Charlie Barts, and I think that when these factors were discussed, they sort of agreed that Charlie Barts should just scare me.

Even more bitter to take than the just getting fired, they barred me out of Small’s. I could understand. Even if I wasn’t actually what was called “hot,” I automatically was going to be under surveillance now; the brothers had to protect their business. I wasn’t a qualified hustler as yet, but I surely had become schooled in their code. I was broke and on my own again, 18 years old.

Sammy, “Pretty Boy,” one of the pimps, proved to be my friend in need. He put word on the “wire” for me to come over to his place. I went; I never had been there. His place seemed to me a small palace; his women really kept him in style. While we talked, about what kind of a hustle should I best get into, Sammy had the best marijuana I’d ever used. Peddling reefers, Sammy and I pretty soon agreed, was the best thing. Both Sammy and I knew some merchant seamen, and others, who could supply me with loose marijuana. And musicians, among whom I had so many good contacts, were the heaviest consistent category market for reefers—and then they also were for the heavier narcotics if I later wanted to graduate to peddling them. I had the advantage that I had been around long enough to either know, or spot on sight, most regular detectives and cops, though not the narcotics people. Sammy staked me, about $20.

I sold reefers like a wild man. Every day I cleared at least thirty or forty dollars. I felt, for the first time in my life, that great feeling of free! Suddenly, now, I was the peer of other smooth young hustlers around.

The narcotics-squad detectives didn’t take long to pick up that I was selling, and different ones of them would tail me once in a while. One morning, though, I came in and found my room ransacked. It was then that I began carrying a little .25 automatic. I carried it stuck right down the center of my back, pressed under my belt. Someone had told me that the cops never hit there when they gave you any routine patting-down. I sold less than I had before because, mainly, being careful consumed so much time, it was on the wire, finally, that the narcotics squad of Harlem had me on its “special list.” Now was when, every other day or so, and usually in some public place, some of them would come up, and flash the badge to search me. But I would tell them right off. loud enough for others to hear me, people standing about, that I didn’t have anything on me, and I didn’t want to get anything “planted” on me, and then they wouldn’t, because Harlem already thought little enough of the law, and they did have to be careful that some crowd of Negroes, figuring they had witnessed a “frame,” could set off even a race riot

A Boston draft board, after I didn’t respond at Ella’s, had contacted her, and then had contacted their New York counterpart, and, in care of Sammy, I received Uncle Sam’s “Greetings.” I had about 10 days to go before I was to show up at the induction center. And I went right to work. I knew I wasn’t even about to get hooked into any Army!

The Army “intelligence” soldiers, those black spies in civilian clothes that hung around in different places with their ears open for the white man downtown, oh, yes, I knew right where to start dropping the word! I started dropping it around that I was frantic to join—the Japanese Army, When I sensed, knew, that I had the direct ears of some of the “spies” I would talk, and act, high and crazy I’d snatch out, and read loudly, my Greetings—to make certain they got who I was, and when I’d report downtown.

And the day I went down there—well, I costumed like a model. With my wild zoot suit and the yellow knob-toe shoes, and I frizzled my hair up into a crazy reddish bush of conk.

Let me tell you—when I went in skipping and tipping, and thrust my tattered Greetings at the reception desk’s white soldier—”Crazy-O, Daddy-O, get me moving, I can’t wait to get in that brown”—why I will bet you that soldier hasn’t recovered from me yet. They had their wire from uptown on me, all right—I could tell from his expression when his glance at my Greetings confirmed the name to him.

“Kill up crackers”

But they still put me in the line. And I had meanwhile sized up the situation. In that big starting room were maybe 40 or 50 other planned inductees. The room had fallen vacuum-quiet, with me running my mouth a mile a minute, talking nothing but slang, I was going to fight on all fronts; I was going to be a general, man, before I got done, and such talk as that.

Most of them in there were white, of course. The tender-looking ones appeared ready to run from me. Some others had on that vinegary “here’s the worst kind of nigger” look. And a few were amused at the “Harlem jigaboo” archtype.

Also amused were some of the room’s maybe 10 or 12 Negroes. But the stony-faced rest of them looked as though if they were about to sign up to go off killing somebody, they would have liked to start killing me right there.

You see, why I made these Negroes really so mad was they were these integration-type Negroes. And what I was doing was confirming white people’s image of Negroes right there among some of the white people that they were so anxious to get integrated with. And they knew those crackers probably would go to their graves fighting integration, after the show I was putting on.

The line moved along. Pretty soon, stripped to my shorts, I was making my eager-to-join comments in the medical examination rooms—and everybody in the white coats that I saw had 4-F in his eyes. I went all the way, though, which was longer than I had expected, before they siphoned me off. One of the white coats accompanied me around a turning hallway; I knew we were on the way to a “headshrinker,”

I must say this for that psychiatrist. He tried to be objective and professional in his manner. He sat there and doodled with his blue pencil on a tablet, listening to me spiel to him probably three or four minutes before he got a word in. His tack was quiet questions, to get at why was I so anxious. I kept jerking around, backward, as though somebody could be listening. I knew I was going to send him back to the books to figure what kind of a case I was.

Suddenly, I sprang up and peeped under both doors, the one I’d entered and another that probably was a closet. And then I bent and whispered fast in his ear, “Daddy-O, now you and me, we’re from up north here, so don’t you tell nobody . . . I want to get sent down South. Organize them nigger soldiers, you dig? Steal us some guns, and kill up crackers!”

A 4-F card came in the mail, and I never heard from the Army anymore.

Because of my reputation around it was easy for me to get into the numbers racket—about the only hustle left in Harlem that hadn’t fallen off in business. My job now was to ride a bus across the George Washington Bridge, where a fellow who was always waiting would hand me a bag of numbers-betting slips. We didn’t speak. I’d cross the street and catch the next bus back to Harlem. I never knew who that fellow was. I never knew who picked up the betting money for the slips that I picked up. In the rackets you don’t ask questions. My boss, his wife and their daughter would be waiting in a room when I would arrive, just shortly before the day’s first number was announced from downtown.

Our numbers-world ethics code was that I should play with a runner of my own outfit. That was how I began placing bets with “West Indian Archie.” This was one of Harlem’s really bad Negroes, one of those former Dutch Schultz strong-arm men who were around. It was status and class just to be known as a client of West Indian Archie.

One afternoon West Indian Archie paid me $300 out of his pocket for a 50-cent-combination bet. I was planning to go out on a date. Later, when I got to the apartment of my friend Sammy, he told me that West Indian Archie had been there, looking for me, I couldn’t figure out why. Anyway, Sammy and I sniffed some cocaine to kill the time before I would go out and pick up my date. Then there was the knocking at the door. Sammy, lying on his bed in pajamas and a bathrobe, called “Who?”

When West Indian Archie answered, Sammy slid under the bed that round, two-sided shaving mirror with what little of the cocaine powder—or crystals, actually—was left, and I opened the door.

“Red—I want my money!”

“Man—what’s the beef?”

West Indian Archie said he’d thought I was trying something when I’d told him I’d hit a 50-cent-combination number. But he’d gone on and paid me the $300 until he could double-check his actual written betting slips; now he thought I hadn’t combinated the number I’d claimed, but another number.

“I’ll give you until twelve o’clock tomorrow to get that money back.” And that mad, mean West Indian put his hand behind him and pulled open the door. He backed out, and slammed it. It was a classic hustler-code impasse. The $300 wasn’t the problem. I had maybe about $200 of it. But once the wire had it, any retreat by either of us was unthinkable. The wire would be awaiting the report of the big showdown. I could see people who knew me finding business elsewhere. I knew nobody wanted to be maybe caught in a crossfire.

I just stayed high for a few days, but I was scared.

Some raw kid hustler in a bar, I had to bust in his mouth. He came back, pulling a blade; I would have shot him, but somebody grabbed him. As I was known, and they feared me, they put him out, cursing that he was going to kill me.

Things were building up, closing in on me. I was trapped in cross turns. West Indian Archie gunning for me. The scared kid hustler I’d hit. The cops.

When I heard the car’s horn, I was walking on St. Nicholas Avenue. But my ears were hearing a gun. I didn’t dream the horn could possibly be for me.

“Homeboy!”

I jerked around; I came that close to shooting. . . .

Shorty—from Boston!

I’d scared him nearly to death.

“Daddy-O l”

I couldn’t have been happier to see my mother! I knew Shorty had hit his number and that he was playing dates around Boston with his own band.

Inside the car he told me Sammy had telephoned how I was jammed up tight and he’d better come and get me. I didn’t put up any objections to leaving town. I brought out and stuffed into the car’s trunk what little stuff I cared to hang onto. Then we hit the highway and drove back to Boston. He afterward told me that through just about the whole ride back, I talked all out of my head.

My sister Ella couldn’t believe how atheist, how uncouth I had become. Even Shorty, whose Boston apartment I now again shared, wasn’t prepared for how I lived and thought like a predatory animal.

Sophia’s being back around was one of Shorty’s biggest kicks about my homecoming. It just happened that Shorty was “between” women when one night Sophia brought to the house and introduced her 17-year old sister. I never saw anything like the way that she and Shorty nearly jumped for each other. For him, she wasn’t only a white girl, but a young white girl. For her, be wasn’t only a Negro, but a Negro musician.

Now I knew that I’d have to have a hustle. Just satisfying my cocaine habit alone cost me about $20 a day. I guess another $5 a day could have been added for reefers and just plain tobacco.

When I opened the subject of house burglary with Shorty, he really shocked me by how quickly he agreed. Shorty wanted to bring in with us this friend of his, whom I had met, and liked, called “Sonny.” He worked regularly for an employment agency that sent him to wait on tables at exclusive parties at exclusive people’s homes. I felt that Shorty was absolutely right in wanting Sonny to join us in burglarizing homes. A good burglary team included a “finder”—one who locates lucrative places to rob. Then another principal need is someone able to “case” these places’ physical layouts—to determine means of entry, the best getaway routes, and so forth. Sonny qualified as a two-in-one find. By being sent to work in the finest homes, he wouldn’t be suspected when he sized up their loot and cased the joint, just running around looking busy with a white coat on.

Our “fence” didn’t work with us directly. He had a representative, an ex-con, who dealt with me and no one else in my gang. You would be surprised how efficient we became. In no time we’d be running with the stolen loot to the parked car that took off for the “drop” previously arranged between me and the representative for the fence. We were going along fine. We’d make a good pile and then lie low a while, living it up. We’d time the burglaries so that Shorty still played with his band. Sonny never missed table-waiting at his exclusive parties.

But it’s a law of nature that every criminal expects to get caught. I had put a stolen watch into a jewelry shop for its broken crystal to be replaced. It was about two days later, when I went to pick up the watch, that things fell apart. I had on my gun in the shoulder holster, under my coat. The loser of the watch, the person from whom it had been stolen, had described the repair that it needed. It was a very expensive watch, that’s why I had kept it for myself. And all of the jewelers in Boston had been alerted. That’s how I was arrested.

The judge gave Shorty eight to 10 years. I got 10 years. They took Shorty and me, handcuffed together, to the state prison in Charlestown. This was in February, 1946. I wasn’t quite to the formal manhood age of 21.

In that Charlestown jail I found out fast you could buy drugs. But I made so much trouble and spent so much time in solitary that I sweated out all my habits “cold turkey.” Many times I thought I was going to die—but even this was only part of the total transformation that was to come over me.

My brothers and sisters began sending me letters about a new, natural religion for the black man. One day Reginald wrote, “Don’t eat any more pork.” I tried it and did it, and for the first time in a long while I began to get a little feeling of self-respect, though I hardly knew even how to identify the feeling. Reginald wrote more, about the worship of Allah and the American teacher of Islam, the Honorable Mr. Elijah Muhammad. I learned that when Mr. Muhammad went to Detroit he actually stayed at my brother Wilfred’s place. It was my sister Hilda who told me that Mr. Muhammad himself had been in prison, for draft dodging, and she suggested that I write to him. And on one visit she explained to me the key lesson of Elijah Muhammad’s teachings, which I later learned was the “demonology” that every religion has. Called “Yacub’s History,” once it is accepted by any black man, he will never again see the white man with the same eyes.

First, the moon separated from the earth. Then, the first humans, Original Man, were a black people. They founded the Holy City Mecca.

Among this black race were 24 wise scientists. One of the scientists, at odds with the rest, created the especially strong black tribe of Shabazz, from which America’s Negroes, so-called, descend.

About 6,800 years ago, when 70 percent of the people were satisfied, and 30 percent were dissatisfied, was born a “Mr. Yacub.” He was born to create trouble, to break the peace, and to kill. His head was unusually large. When he was four years old, he began school, on the way to becoming highly educated.

At the age of 18, Yacub had finished all of his nation’s colleges and universities. He was known as “the big-head scientist.” Among many other things he had learned how to scientifically breed races.

This big-head scientist, Mr. Yacub, began preaching in the streets of Mecca, making such hosts of converts that the authorities, increasingly concerned, finally exiled him with his 59,999 followers to the island of Patmos—described in the Bible as the island where John supposedly received the message contained in Revelations in the New Testament.

Though he was a black man, Mr. Yacub, embittered toward Allah now, decided, as revenge, to create upon the earth a “devil” race—a bleached-out, white race of people!

He knew that it would take him several total color-change stages to get from black to white. Mr. Yacub began his work by setting up a birth-control law there on the island of Patmos.

There, among Mr. Yacub’s 59,999 followers, every third or so child that was born would show some trace of brown. As these became adult, only brown and brown, or black and brown, were permitted to marry. As their children were born, Mr. Yacub’s law dictated that, if a black child, the attending nurse or midwife should stick a needle into its brain and give the body to cremators. The mothers were told it had been an “angel baby,” which had gone to heaven, to prepare a place for her.

But a brown child’s mother was told to take very good care of it.

Others, assistants, were trained by Mr. Yacub to continue his objective. Mr. Yacub, when he died on the island at the age of 152, had left laws and rules for them to go by. Mr. Yacub, except in his mind, never saw the “bleached-out devil race” that his procedures created.

A 200-year span was needed to eliminate on the island of Patmos all of the black people—until only brown people remained.

The next 200 years were needed to create from the brown race the red race—with no more browns left on the island.

In another 200 years from the red race was created the yellow race.

Two hundred years later—about 6,000 years ago—at last, the white race had been created.

On the island of Patmos was nothing but these blond, pale-skinned, cold-blue-eyed devils—savages, nude and shameless; hairy, like animals, they walked on all fours and they lived in trees.

Six hundred more years passed before this race of people returned to the mainland among the natural black people.

Within six months of time through telling lies that set the black men to fighting among each other, this devil race had turned what had been a peaceful Heaven on earth into a hell torn by quarreling and fighting. Then the whites ruled.

It was written that after Yacub’s bleached-white race had ruled the world for 6,000 years—down to our time—then the black original race would give birth to one whose wisdom, knowledge and power would be infinite. It was written that some of the original black people should be brought as slaves to North America—to learn to better understand, firsthand, the white devils’ true nature, in modern times.

The greatest and mightiest God who appeared on the earth was Master W. D. Fard. He came from the East to the West, appearing in North America at a time when the history and the prophecy was coming to realization, as the nonwhite people all over the world began to rise.

Master W. D. Fard, in 1931, posing as a seller of silks, met, in Detroit, Mich., the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He gave Allah’s message to Elijah and Allah’s divine guidance, to save “the Lost-Found Nation of Islam,” the so-called Negroes, here in “this wilderness of America.”

When my sister, Hilda, had finished telling me this “Yacub’s History,” she left. I don’t know if I was able, even, to open my mouth and tell her “good-bye.”

I did write to The Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He sent me a typed reply. It had an all but electrical effect on me to actually see the signature of the Messenger of Allah. He told me to have courage. He even enclosed some money for me, a five-dollar bill. Mr. Muhammad to this day sends money all over the country to prison inmates who write to him.

I began pretty soon to write to people in the hustling world that I had known, such as my close friend Sammy, the pimp, or the different dope peddlers. I told them all about Allah and Islam and Mr. Elijah Muhammad. What surely went on the Harlem and Roxbury wires was that “Detroit Red,” in “stir,” either was going crazy, or he was trying some “hype” to shake up the warden’s office, through writing what the prison censors obviously would report.

I got frustrated at how I couldn’t express what I wanted to convey in letters. When I started trying to figure what to do about that, I saw that the best thing I could get hold of was a dictionary to study, to learn some words. Probably I spent two days just uncertainly riffling through the pages of that dictionary. I never had realized there were so many words. I didn’t know which words for a better vocabulary! Anyway, finally, the only way I saw to just start some kind of action, I began copying—In a couple of weeks, without having had any original intention in the world of even thinking of doing such a thing, the A section of the dictionary had filled a whole tablet, and I just naturally went on into the B’s. That was the way I started copying, eventually, the entire dictionary. It went a lot faster after, through the practice. I had picked up handwriting speed.

It was inevitable, I suppose, that as my word base broadened, for the first time, I could pick up a book and actually understand what the book was saying.

I had meanwhile been transferred to Norfolk Prison Colony, a rehabilitation center for model prisoners. This was because my disposition had improved and because Ella was working for me with the authorities outside. Let me tell you something! From then until I left that prison, within its routine, in all of the free time I had, I was in the library picking up some more books.

Two other areas of experience which have been extremely formative in my life were first tasted there in prison. For one thing I had my first experiences in communicating Mr. Muhammad’s teachings to some of the black prisoners. And. the other thing, when I had read enough to know something to talk with, I began to get into the weekly debating program—my baptism into public speaking.

I’d “knock out” my brother Reginald when he visited me in prison, telling him things I’d found that documented the Muslim teachings.

But Reginald, I learned later, had actually been suspended from the Nation of Islam by The Messenger Elijah Muhammad, charged with immorality. After he had learned the truth, and had accepted the truth and the laws of the Muslim, he still was reportedly carrying on improper relations with some woman of his who lived in New York. Some other Muslims who learned of it had made charges against Reginald to Mr. Muhammad in Chicago, and Mr. Muhammad had suspended Reginald.

I was in a torment. Finally, I wrote to Mr. Muhammad, trying to defend my brother, appealing for him. I told him what Reginald was to me, what my brother meant to me. I put the letter into the box for the prison censor. Then, all of the rest of that night, I prayed to Allah. I don’t think that anyone ever prayed more sincerely to Allah. I prayed for some kind of relief from my terrible confusion.

It was that night, or, rather, it was the next night, I lay on my bed. And I suddenly, with a start, became aware of a man sitting beside me in my chair. He had on a dark suit, I remember. I could see him as plainly as I see anyone I look at. He wasn’t black, and he wasn’t white. He was light-brownskinned, an Asiatic complexion, and had oily black hair.

He just sat there. Then, as suddenly as he had come, he was gone. Later, of course, I learned that my prevision was of Master W. D. Fard, the Messiah, who had appointed Mr. Elijah Muhammad as His Last Messenger to the black people of North America.

Greater than Allah

Gradually I saw the chastisement of Allah—what Christians would call “the curse” come upon Reginald. He had begun to lose his mind—as we know it. In prison, since I had become a Muslim, I had grown a beard. He visited me, he moved nervously about in his chair; he told me that each hair of my beard was a snake. He saw snakes everywhere.

He next began to believe that he was the Messenger of Allah. He went around in the streets of Roxbury, Ella relayed to me, telling people that he had some divine power. He graduated from that to saying that he was Allah.

And, finally, he began saying that he was greater than Allah.

Authorities picked up Reginald, and he was put into an asylum, and stayed.

It was spring, 1952, when I joyously wrote to Mr. Elijah Muhammad and to my family that the Massachusetts state parole board had voted that I should be released. My record was good, and it may have helped that they knew I was a Muslim. Maybe they wanted me removed from spreading Mr. Muhammad’s teachings among other Negro convicts. I was paroled into the custody of my oldest brother, Wilfred, in Detroit, who now managed a furniture store. Wilfred got the man who owned the store to sign that upon release I would immediately be given employment. Wilfred invited me to share his home and I gratefully accepted.

The furniture store that my brother Wilfred managed was right in the black ghetto of Detroit. Nothing Down advertisements drew poor Negroes into that store like flypaper! It was a shame, the way they paid probably three and four times what the furniture had cost, because they could get credit. It was the same kind of cheap, gaudy-looking junk that you can see in any of the black ghetto furniture stores today. Fabrics were stapled on the sofas. Imitation “leopard skin” bedspreads, “tiger skin” rugs, such stuff as that. I would see clumsy, calloused hands scratching the signatures on the contract, agreeing to highway-robbery interest rates in the fine print that never was read.

Mosque No. 1 in Detroit was the first mosque to be formed, back in 1931, by Master W. D. Fard and the Messenger Elijah Muhammad. I had never seen any Christian-believing Negroes conduct themselves like the Muslims who came, the individuals and the families alike. The men were quietly, tastefully dressed. The women wore ankle-length gowns, no makeup, and scarves covered their heads. The children were mannerly and neat.

On the Sunday before Labor Day in 1952 Detroit Mosque No. 1 Muslims went in a motor caravan, about 10 automobiles of us, to visit the Chicago Mosque No. 2, to hear, in person, The Messenger Elijah Muhammad.

I was unprepared, totally, for the Messenger Elijah Muhammad’s physical impact upon my emotions. From the rear of Mosque No. 2 he came toward the platform. The small, brown face, the sensitive, gentle face that I had studied on photographs until I had seen it in dreams, was fixed straight ahead as the Messenger strode, encircled by the marching, strapping “Fruit of Islam” guards. The Messenger, compared to them, seemed fragile, almost tiny. He and the Fruit of Islam were dressed in dark suits, white shirts and bow lies. The Messenger wore a gold-embroidered fez. Hearing his voice, I sat leaning forward, riveted upon his words. That Sunday after the meeting Mr. Muhammad, who had been Wilfred’s houseguest, invited our entire family group and minister Lemuel Hassan to be his guests for dinner at his new home.

I talked with my brother Wilfred back in Detroit. I offered my services to our mosque’s minister, Lemuel Hassan. He shared my determination that we should apply the Messenger’s methods in a recruitment drive. Beginning that day, every evening, straight from work at the furniture store, I went doing what we Muslims later came to call “‘fishing.” I knew the streets’ language, and its thinking. “My man, let me pull your coat to something—”

My application had, of course, been made, and I received from Chicago my “X” during this time. The X for the Muslim was a symbol for the true African family name that he never could know; it would replace the white-slave-master name which had been imposed upon my paternal forebears by some blue-eyed devil. It meant, the receipt of my X, that in the Nation of Islam thereafter I would be known as Malcolm X.

Within a few months of our plugging away, our storefront Mosque No. 1 about tripled its membership. And we had so deeply pleased Mr. Muhammad that he paid us the honor of a personal visit. He gave me warm praise when minister Lemuel Hassan expressed how hard I had labored in the cause of Islam.

And soon after that minister Lemuel Hassan urged me to make an extemporaneous lecture to the brothers and sisters. I was hesitant—but at least I had debated in prison. I tried my best.

In the summer of 1953—all praise is due to Allah—I was named Detroit Mosque No. 1’s assistant minister. Every time I could get off, I would go to Chicago and see Mr. Elijah Muhammad, He encouraged me to come when I could. I felt like, and I was treated like, another son, or another brother, by Mr. Muhammad and his dark, good wife Sister Clara Muhammad, and their children, and his dear mother, Mother Marie.

I would sit, galvanized, hearing from Mr. Muhammad’s own mouth the true history of our religion, the true religion for the black man. Mr. Muhammad told me that he one evening had a revelation that Master W. D. Fard represented the fulfillment of the prophecy, that on the Last Day the Messiah would come as lighting from the East and appear in the West to resurrect the Lost Sheep and restore them forever to their own people.

In 1934, ready to leave, Master W. D. Fard called together all of his ministers. He instructed them that Mr. Elijah Muhammad was to be the Messenger to the Lost-Found Nation of Islam—who was the black man—in the wilderness of North America.

Then Master W. D. Fard disappeared without a trace.

Mr. Muhammad invited me to live at his home in Chicago while he trained me for months. Then in March, 1954, the Messenger moved me on to Philadelphia. The City of Brother Love black people reacted fast. And Philadelphia’s Mosque No. 12 was established by the end of May. It had taken a little under three months.

The next month, because of that Philadelphia success, Mr. Muhammad appointed me to be the minister of Mosque No. 7—in vital New York City! It was nine years since West Indian Archie and I had been stalking the streets, momentarily expecting to try and shoot each other down like dogs.

When I got back to Harlem I quickly found out from the wire that West Indian Archie was just another penniless old man. I went to see him and he told me, “Red! I am so glad to see you!” I pressed some money on him and told him a little about the Nation of Islam. I also found out that Shorty was out of jail and had another small band. Sammy, the pimp, they told me had married a young girl, and then been found dead across his bed one morning—they said with $25,000 in his pockets.

I keep having to remind myself that then Mosque No. 7 in New York City was a little storefront. We discovered the best fishing audience of all, by far the best conditioned audience for Mr. Muhammad’s teachings: the Christian churches. We went fishing fast and furiously when those little evangelical store front churches let out their 30 to 50 people on the sidewalk. “Come to hear us, brother, sister—” These congregations were usually Southern-migrant people, usually older people, who would go anywhere to hear what they called “good preaching.” These were the church congregations who were always putting out little signs announcing that inside they were selling fried-chicken-and-chitterlings dinners to raise some money. And three or four nights a week they were in their storefront rehearsing for the next Sunday, I guess, shaking and rattling and rolling the Gospels with their guitars and tambourines. I knew the mosque that I could build if I could really get to those Christians.

But I knew also that our strict moral code of disciplines was what repelled them most. I fired at this point, at the reason for our code: “The white man wants black men to stay immoral, unclean and ignorant.”

The code, of course, had to be explained to any who were tentatively interested in becoming Muslims. Any fornication was absolutely forbidden in the Nation of Islam. Any eating of the filthy pork, or other injurious or unhealthy foods; any use of tobacco, alcohol or narcotics. No Muslim could dance, gamble, date, attend movies, or sports, or take long vacations from work. Muslims slept no more than health required. Any domestic quarreling, any discourtesy, especially to women, was disallowed. No lying, or stealing was permitted, or no insubordination to civil authority, except on the grounds of religious obligation.

Our moral laws were policed by our Fruit of Islam—able and dedicated and trained Muslim men. Infractions resulted in suspension by Mr. Muhammad, or isolation for various periods, or even expulsion for the worst offenses, “from the only group that cares about you.”

We had grown, by 1956—well, sizable. Every mosque had fished with enough success that there were far more Muslims especially in the major cities of Detroit, Chicago and New York than anyone ever would have guessed from the outside. In fact, as you know, in the really big cities you can have a very big organization that, if it makes no public show, or noise, no one will be aware that it is around.

I haven’t made any mention of it before now, but I had always been so very careful to stay completely clear of any personal closeness with any of the Muslim sisters. My total commitment to Islam demanded having no other interests, especially, I felt, no women. But I hadn’t been involved with many mosques where at least one single sister hadn’t let out some broad hint that she thought I needed a wife.

Then this particular sister—well, in 1956, she joined Mosque No. 7. I just noticed her, not with the slightest interest, you understand. For about the next year I just noticed her. You know. It was Sister Betty X. She was tall. Brown-skinned—darker than I was. And she had brown eyes. But I didn’t pay too much attention.

I knew she was a native of Detroit, and that at Tuskegee Institute down there in Alabama, she had been a student—an education major. She was in New York attending one of the big hospitals’ School of Nursing. She lectured to the Muslim girls’ and women’s classes on hygiene and medical facts.

One day I thought it would help the women’s classes if I took her—just because she happened to be an instructor—to the Museum of Natural History. I wanted to show her some museum displays having to do with the family tree of evolution that would help her in her lectures. I could show her actual proofs of Mr. Muhammad’s teachings of such things as that the filthy pig is only a large rodent. The pig is a graft between a rat, cat and dog, Mr. Muhammad taught.

Then, right after that, one of the older sisters confided to me a personal problem that Sister Betty X was having. When Sister Betty X had told her foster parents, who were financing her education, that she was a Muslim, they had given her a choice: leave the Muslims, or they’d cut off her nursing-school financing.

I got to turning it over in my mind. What would happen if I just should happen, sometime, to maybe think about maybe getting married to somebody? I was so shocked, at myself, when I realized what I was thinking, I quit going anywhere around Sister Betty X, or anywhere I knew she would be. Because she sure wasn’t going to have any chance to embarrass me. I had heard too many women bragging, like, “I told that chump ‘Get lost!’ ” I’d had too much of all kinds of experience to make a man very cautious.

But I told The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, when I visited him in Chicago that month, that I was thinking about a very serious step. He smiled when he heard what it was. Mr. Muhammad said that he’d like to meet this sister.

The Nation by this time was financially able enough that the expenses could be borne for different instructor sisters, from different mosques, to be sent on a trip to Chicago to attend the Headquarters Mosque No. 2 women’s classes, and, while there, to meet The Honorable Elijah Muhammad in person. Sister Betty X, of course, knew all about this, so there was nothing for her to think when it was arranged for her to go to Chicago. And like all visiting instructor sisters she was the houseguest of The Messenger and Sister Clara Muhammad.

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad told me that he thought that Sister Betty X was a fine sister, who would make a good Muslim wife. I proposed to her direct, “Look, do you want to get married?” She acted all surprised and shocked. The more I have thought about it, to this day I believe she was putting on an act. Because women know.

On the fourteenth of January, 1958, a Tuesday, we had driven out to Lansing, Mich., where my brother Philbert lived. We got the necessary blood tests, then the license. Then we went to the justice of the peace.

An old hunchbacked white devil performed the wedding. And all of the witnesses were devils. Where you are supposed to say all those “I do’s,” we did. They were all standing there, smiling and watching every move. The old devil said, “I pronounce you man and wife,” and then, “kiss your bride.”

I got her out of there. All of that Hollywood stuff! Like these women wanting men to pick them up and carry them across thresholds, and some of them weigh more than you do. I don’t know how many marriage breakups aren’t caused by these movie- and television-addict women expecting some bouquets and kissing and hugging and being swept out like Cinderella for dinner and dancing—then getting mad when a poor, scraggledy husband comes in tired and sweaty from working like a dog all day, looking for some food.

We lived for the next two-and-a-half years in Queens, New York, sharing a house of two small apartments with Brother John Ali and his wife. He’s the national secretary in Chicago.

Attilah, our oldest daughter, was born in November, 1958. She’s named for Attilah the Hun. (He sacked Rome.) Shortly after Attilah came, we moved to our present seven-room home in an all-black section of Queens.

Another girl, Quiblah (named after Emperor Kubla Khan), was born on Christmas Day of 1960. Then, Ilyasah (“Ilyas” is Arabic for Elijah) was born in July, 1962. We have just had a fourth child, who was going to be named “Lamumba,” but it turned out to be another girl. And she has the feminine form, “Lamumbah,” with an “h.”

You know—any husband observes his wife, just like the other way around, the wife observes the husband. I guess by now I will say I love Betty. She’s the only woman I ever even thought about loving. And she’s one of the very few—four women—whom I have ever trusted. The thing is, Betty’s a good Muslim woman and wife. You see, Islam is the only religion that gives both husband and wife a true understanding of what love is. The Western “love” concept, you take apart, it really is lust. But Islam teaches us to look into the woman, and teaches her to look into us.

During the next years, radio and television people began asking me to defend our Nation of Islam’s program in “panel discussions” and “debates” against handpicked “scholars,” both whites and some of those Ph.D. “house” and “yard” Negroes who had been attacking us.

Dr. C. Eric Lincoln’s book about us was published amid widening controversy about us Muslims, just about the time that we were starting to put on our first big mass rallies. Now this book’s title was Black Muslims in America. And we never could get that “Black Muslim” name dislodged. Later Mr. Muhammad directed that we would admit the white press. Fruit of Islam men thoroughly searched them, as everyone else was searched—their notebooks, their cameras, camera cases, and whatever else they carried. We were watched. Our telephones were tapped. If I said on my home telephone right today, “I’m going to bomb the Empire State Building,” I guarantee you that in five minutes it would be surrounded. Speaking publicly, sometimes I’d guess which races in the audience were FBI or other types or agents. Both the police and the FBI intently and persistently visited and questioned us. Mr. Muhammad said, “I do not fear them, I have all that I need, the truth.”

And so, by 1961, our Nation of Islam flourished. Mr. Muhammad evidenced the depth of his trust in me. In certain areas he told me to make decisions myself. “Brother Malcolm, I want you to become well known,” Mr. Muhammad said to me. “But, Brother Malcolm, there is something that you need to know. You will grow to be hated when you become well known. Because usually people will get jealous of public figures.” Nearly every day some attack on “the Black Muslims” appeared in newspapers. Increasingly, a focal target was something I had said, or “Malcolm X” as an individual “demagogue.”

Because as the Nation of Islam’s minister in New York City in 1963, I was trying to cope with the newspaper and television reporters determined to defeat Mr. Muhammad’s teachings.

The New York Times reported me to be, according to a poll which the Times had made on college and university campuses, “the-second-most-sought-after” speaker at colleges and universities. The speaker ahead of me, “most-sought-after,” was Sen. Barry Goldwater.

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, each time I would go to see him in Chicago, or Phoenix, would warm me with his expressions of his approval and confidence in me. He left me in charge of the Nation of Islam’s affairs when he made a pilgrimage to the Holy City, Mecca. I would have hurled myself between Mr. Muhammad and an assassin.

Now as far back as 1961, I had heard chance negative remarks concerning me, or veiled negative implications, or I noticed other early evidences of the envy and jealousy which Mr. Muhammad had prophesied. I was trying to “lake over” the Muslims. I was “taking credit for Mr. Muhammad’s teaching.” I was “trying to build an empire” for myself. I loved playing coast-to-coast “Mr. Big Shot.” But I don’t believe that any man in the Nation of Islam could have gained the international prominence that Mr. Muhammad’s wings had let me gain—plus the freedom that he had granted me to take liberties and do things on my own—and still have remained as faithful and as selfless a servant as I was. Yet I was very hypersensitive to internal critics.

Also, I could not help but hear some of the hints and rumors and vicious gossip that was going around, about the moral behavior of our leader. Just to hear these stories, why, it made me spooky with fear! But the stories got worse and even people outside the Nation began to hear them. I will only note, to be as brief as possible on this and to indicate my own reactions, that Mr. Muhammad is the defendant in two paternity suits in Los Angeles. I don’t know how those suits, from two girls who once were his secretaries, are going to come out, but I do know that at the time I first heard those wicked speculations about his moral life, I could not ignore them.

By late 1962, a number of Muslims were leaving Mosque No. 2 in Chicago. I learned that reliably—and the ugly rumor was spreading swiftly there among non-Muslims, as well. So some months later I sat down and I wrote to Mr. Muhammad what poison was being spread about him. He had me to fly to his new home in Phoenix to see him in April, 1963.

We embraced, as always; and almost immediately he took me outside, where we began to walk by his swimming pool. “Well, son,” he said, “what is on your mind?” Plainly, frankly, pulling no punches, I told Mr. Muhammad what was being said. And without waiting for any response from him, mentioned Bible passages about the sins of David, Moses, and Noah and discussed with him about how good deeds outweighed bad, and about the fulfillment of prophecy.

“Son, I’m not surprised,” Elijah Muhammad said. “You always have had such a good understanding of prophecy, and of spiritual things. You recognize that’s what all of this is—prophecy. You have the kind of understanding that only an old man has.

Submission

“I’m David,” he said. ‘”When you read about how David took another man’s wife, I’m that David. You read about Noah, who got drunk, that’s me. You read about Lot, who went and laid up with his own daughters, I have to fulfill all of those things.”