(The Malcolm X I Knew was originally published in the November 1965 issue of Saga Magazine—the same month The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published.)

(The Malcolm X I Knew was originally published in the November 1965 issue of Saga Magazine—the same month The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published.)

Note: Below is the transcription of a manuscript version of Alex Haley’s essay The Malcolm X I Knew, originally published by Saga magazine in November 1965, the same month in which The Autobiography of Malcolm X was published.

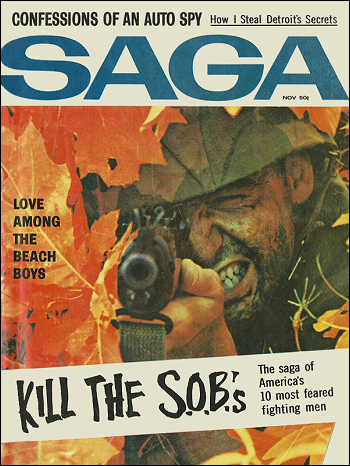

Saga was a pulp men’s magazine published by New York’s Gambi Publications. Articles such as “Confession of an Auto Spy,” “How Sex Can Take You to the Top,” and “Love Among the Beach Boys” appear in the same issue as Haley’s essay along with drawings of scantily clad women and ads promising to remedy baldness.

The manuscript version is substantially longer than the published essay, which we cannot reproduce due to copyright restrictions.

While some of the scenes contained within the essay are echoed in The Autobiography, new materials is included, such as Malcolm X’s interaction with a white couple in New York City.

The essay provides one more lens through which to examine the working relationship of X and Haley as well as the ways Haley shaped the narrative. The manuscript from which these materials are transcribed is housed in the Alex Haley Papers held by Cushing Library, Special Collections, at Texas A&M University.

Scholarly Editing: The Annual of the Association for Documentary Editing is freely distributed by the Association for Documentary Editing and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Malcolm X I Knew

Malcolm X. and I rode downstairs in a New York Hilton Hotel elevator and outside a revolving door he handed a garage attendant his car check. As we stood chatting, a middle-aged white couple came up to also order their car, and the husband pleasantly observed to us that New York City’s weather was excellent. It certainly was, replied Malcolm X. The man, with an open, sincere friendliness, introduced himself and his wife, giving their name and their Florida hometown. Malcolm X., warmly responding, shaking the man’s extended hand and bowing toward his wife in a courtly manner, said, “My name’s Shabazz. I’m a native of Michigan.” A brief, affable conversation ensued before Malcolm X.’s blue Oldsmobile was delivered and with an exchange of smiling goodbyes, we got inside the car. Before driving away, Malcolm X. bent his head to wave again at the white couple.

But we looked into their faces suddenly now as blanched and slack as if they stared at the devil. The garage attendant obviously had identified Malcolm X. The blue Oldsmobile gunned out to the street. “I wish he hadn’t done that!” Malcolm X. exclaimed bitterly.

The incident happened only a few weeks before Malcolm X.’s death. Often since I’ve thought how it vividly reflected the contrast between the publicly average impression of a one-track, vitriolic black demagogue and the private Malcolm X. whom I came to know during working closely with him for two years in the process of writing his autobiography that is soon to be published. That private Malcolm X. was a paradox. He was a man who had packed into his 39 years more high drama than is seen in the average ten men’s lifetimes. As is now generally known, the father of the boy Malcolm was killed, supposedly by whites; the widow burdened with seven children and meager income gradually lost her mind and was institutionalized; Malcolm, as a ward of the state of Michigan, was reared by a white family through his eighth-grade year, and then went to live with his grown half-sister in Boston where he first tasted ghetto life.

Faking his age, he got a railroad dining car job, traveling to New York City, where, captivated by Harlem, he went to work there as a waiter, then he branched out into free-lance hustling, selling dope, women and engaging in various other crimes. When eventually caught and imprisoned with a ten-year sentence, Malcolm as a convict first heard the Black Muslim philosophies of Elijah Muhammad, whose convert he became, and when freed Malcolm’s native talent quickly saw his rise to the Black Muslim’s chief spokesman. In 1959, a television expose had thrust the militant, fiery figure into the public eye, and subsequently he had risen to national and finally international fame.

I came to know a private man of many facets. He was defiant, suspicious; he was almost incredibly self-disciplined; he was also warm, and sensitive, and he was fascinated with people. From the man who indeed gave every impression that he truly hated all white people, I watched him alter what he believed until in the end he grieved that scarcely anyone would accept his declarations that he wanted to work for the brotherhood of all men. It was hard for me to believe since his original stand had been so absolutely convincing. To a white person he would not speak a word that he considered of non-business nature. I watched him stare coldly and fold his arms when a white hand was offered to shake. I saw him turn his back and walk away from white reporters who had either asked or said something of which Malcolm X. disapproved. This was the dramatically militant personality which had captured most of Harlem’s awed admiration when he led 50-odd ominously silent Black Muslim “Fruit of Islam” men to stand in ranks before a police precinct where a brother Muslim, nightsticked by a policeman, had been taken. Malcolm X. had gone into the precinct and demanded that the man be taken to Harlem Hospital, which was done, and the Black Muslims followed and stood outside the hospital, with an excited crowd swelling behind them. A high police official warned Malcolm X. that he had generated a potential riot, to which Malcolm X. replied that his men were standing perfectly disciplined. “Yes, but those others,” said the official, and Malcolm X. said, “Those are your problem.” Later the official told the press, “No one man should have that much power.”

Negro writers—if assigned by white-owned publications—fared no better with Malcolm X. in these days. “You’re another tool of the white man sent to a spy” he told me levelly when I approached him to do an article. He required me to fly to Chicago to obtain the clearance of his leader, Elijah Muhammad, and when this was gained, Malcolm X. grudgingly cooperated. After the article was published, Elijah Muhammad approved of it as having been “fair” and subsequently somewhat thawed toward me, Malcolm X. cooperated with two more articles for other publications [The Saturday Evening Post and Playboy]. It was this background of my successfully working with Malcolm X. that promoted a book publisher to ask me in 1963 if I would try to obtain the exclusive autobiography of “the angriest Negro in America,” as Malcolm X. liked to term himself.

“A—book?” Malcolm X. was taken aback when I put the question to him in Harlem’s Black Muslim Mosque #7 restaurant. He abruptly quit stirring cream into his coffee. (“Coffee’s the only thing I like integrated” was then among his favorite expressions.) Casting me a sharp look, he said, finally, “I will have to give a book a lot of thought.”

I was privately dubious if he would agree, for in the magazine interviews Malcolm X. had displayed what seemed almost a physical aversion to talking about himself, or anything else except the glories of the Black Muslim organization and its leader Elijah Muhammad. But the next weekend, I was highly surprised when Malcolm X. said simply, “I’ll agree—but I don’t want to get one penny from it, I don’t want anybody misinterpreting my motives.” Then he said, “Now, my agreement to a book is subject to Mr. Muhammad’s agreement, you’ll have to ask him.” I flew this time to Phoenix, Arizona, where Elijah Muhammad had a summer home for the dry climate’s relief of his severe bronchial condition. He said that he felt that “Allah approves,” and back in New York Malcolm X. read the publisher’s contract skeptically, signed it, and looked hard at me. “I want a writer—not an interpreter,” he said, and I asked him to personally pledge to me a priority quota of his time for the planned 100,000-word as-told-to Autobiography Of Malcolm X.” that would span his entire life.

Over the next several weeks, I became ready to return to the publisher with news that I couldn’t get Malcolm X. to talk of anything but the Black Muslims and their leader. I kept trying to impress upon my subject that he was the subject, until he snapped, “Nobody puts words in my mouth.” What little rapport between us had been gained with the magazine articles seemed to have evaporated. His visiting my Greenwich Village studio three or four nights a week was the only positive note there was. He was skeptical of everything. He would walk in the door saying, “Testing! Testing!” for he was convinced that the F.B.I. had my studio “bugged.” Another time, he arrived about fifteen minutes earlier than he had said he would, and he met a white friend of mine leaving; he acted as if it confirmed his worst suspicions.

He would pace the floor, haranguing against whites in general and against the prominent Negroes who were attacking the Black Muslims. After having done the same thing all day, Malcolm X. was always tired when he arrived. Then my first break came one night when he was so fatigued he almost stumbled as he walked—and for some reason I followed an impulse and out of the blue I asked him if he would tell me something about his mother.

Malcolm X. stopped pacing, looking oddly at me. And incredibly to me he began to describe in an almost stream-of-consciousness manner the harrassed, distraught widow of his father trying to keep her home and children together on the outskirts of Lansing, Michigan. “—she was always standing over the stove, trying to stretch whatever we had to eat. We stayed so hungry that we were dizzy. I remember the color of dresses she used to wear—they were a kind of faded-out gray . . .”

From that night, Malcolm X. began volunteering to me the chronology of the boyhood years of his life, speaking grimly, as if it was a distasteful job he had contracted to do. I feared now a leaden narrative, but occasionally there would be flashes, glimpses, of some leavening lightness or humor. I remember so well, because it meant so much, the first honest laughter from Malcolm, in which I joined him. He was telling about how his older brother Philbert became a youthful boxer and he, Malcolm, envious, also signed up for an amateur bout. “I was really thirteen, but my height let me get away with claiming I was sixteen, the minimum age, and my weight of about 128 pounds got me a bantamweight classification.” He recalled that he was matched with “Bill Peterson,” a white novice. “The bell came, and I knew I was scared. Bill Peterson told me later on he was scared of me, too. He was so scared I was going to hurt him that he knocked me down fifty times if he did once.” Humiliated, Malcolm X. trained hard for a rematch with Peterson. “This time, the bell rang, I saw a fist, then the canvas coming up, and ten seconds later the referee was saying ‘Ten!’ over me. I lay there, listening to the full count. I couldn’t move, I’m not sure I wanted to move.”

Other lightening glimpses into Malcolm X. came, such as that all of his life he had feared dogs. “Every since I can remember, if I saw a dog no bigger than your hand, it looks to me like a lion. Why, when later on I became a burglar, I wouldn’t go near a house where I heard a dog.” And, on the subject of burglary, “Look, I’ll tell you a better thing than a dog to keep any burglars away. I’m talking from experience. Keep a light burning. And the best place is in the toilet. See, nobody could ever be sure if you were in there or not any time of the night, and a burglar knows if you are in there, you’re especially quiet and you would hear the slightest unnatural noise he might make.”

Malcolm X. was very difficult to keep confined to any specific area of subject. One thing mentioned would spark some other remembrance. He might mention, for instance, how pimps he had known had beaten up their women, and he would divert to his own childhood punishments. “Right then, from my mother, is where I learned one of the most important lessons, to open my mouth and be heard. Whenever my mother even started to raise her hand to hit me, I hollered so loud I alarmed the neighbors and she was so embarrassed she quit hitting me.”

It would appear on some occasions that Malcolm X. suddenly realized that he might have talked for a whole hour without once having lambasted the white man, and without and other evident motivation, he would deliver a tirade. Once I asked him if in the world there was just one white person whom he favored. “None!” He was implacable. “Anytime a black man trust one, he makes a mistake—look what they have already done to us!”

Seguing on the subject of whom he trusted, Malcolm X. said he next least trusted women. “They are the quickest path to a man’s ruination,” and the downfalls of Adam and Samson he cited as examples. He said that he had told his wife he trusted her “only seventy-five percent.” He looked at me. “You I trust twenty-five percent.” I must have looked taken aback and he eased the percentage somewhat by saying, “Why, I don’t even trust myself completely, I’ve seen too many men betray themselves.” The years in crime, then in prison, then in the closely-watched Black Muslims had taken a heavy toll on Malcolm X.’s faith in the human race. Time and again when I took notes rapidly as he delivered some verbal broadside, especially if it was directed at the white race, he would glower and exclaim, “You know that devil’s not going to print that!” When I reminded him that a sizeable advance had been paid by the publisher who knew Malcolm X.’s philosophies before the book was contracted, he scoffed, “You studied in school what the white man wants you taught to think about him. I studied him in the streets where you see the truth.”

An overall awkward quality persisted in the interviewing with Malcolm X.’s penchant for abrupt changes of subject, and when he suggested that I might accompany him on some of his daily rounds, I jumped at the opportunity to talk with him out of the somewhat formal studio setting. It was like discovering an entirely different man on the Monday he said I could join what he called “my little rounds,” explaining that he physically mingled as often as he could with the “downtrodden black man in the slums” whom he talked with “while the other so-called black leaders just talk about.”

Walking in the worst blocks in Harlem, Malcolm X. would exhult to me, “These are the black people down in the gutter where I came from,” and he was indeed regarded here as a symbol. He stopped and talked with dozens of individuals, usually salting his remarks with some subtle Black Muslim proselytizing. “White man wants you drunk, so he can put a club beside your head,” he might tell a sodden wino, or to Negro men with shiny “conked” hair. “Brother, that white devil has taught you to hate yourself so bad that you put hot lye in your hair to look more like his hair.” (Malcolm X. once had “conked” his hair with hot lye for years; one night he gave me a graphic description of the intensely painful process.) The toothy, boyish grin and the well-known repartee charmed stoopfuls of women to the point that probably they would have marched behind Malcolm X. to City Hall if he had asked them. The only ghetto residents whom Malcolm X. tended to avoid were the quasi-“sharply” dressed hustlers such as he once had been. “I know what’s in their heads. They figure nobody can tell them anything, and they’re so ignorant that most of them couldn’t write a sentence, just like I couldn’t. They’re the most tragic figures in the ghetto—and the most dangerous. They’ve got these fifteen and twenty dollar a day dope habits, they’re too ‘hip’ to do anything legitimate—where do you think they get their livings from? Every human being they see is prey.”

One day when Malcolm X. had asked me to go with him to Philadelphia, where he was to do a radio program, we rode in the parlor car on a train (“I can get into trouble on an open coach,” he had said) and soon he nudged me to notice a white-jacketed Negro porter who kept walking through the full car. “I forget his name,” whispered Malcolm X., “but I used to work right on this train with him. He knows me—he’s trying to make up his mind.” Shortly, Malcolm leaned out in front of the oncoming porter. “Why, sure I know you!” the porter suddenly said very loudly. “You washed dishes right on this train. I was just telling some of the fellows you were here in my car. We all follow you!”

In the parlor car filled with white passengers except for the three of us, the tension was nearly physical in feeling. After a few moments, the porter returned, introducing Malcolm X. to a young white passenger, who said loudly he had studied in the Orient and now was at Columbia University. “I admire your oratorical ability, but I don’t agree with everything you say,” he told Malcolm X. Malcolm X. was almost benevolent in manner, “Sir, I don’t believe you could search America and find two men who are in agreement on everything.”

Newspapers along the length of the car had lowered to just below eye-level when another white man, an older businessmen, came and shook Malcolm X.’s hand, and suddenly seemed to forget whatever he had intended to say. “Sir, I know how you feel,” Malcolm X. attempted a rescue. “It’s a hard thing to speak when you are agreeing with so much that I say.” The remainder of the way to New York, Malcolm X. and I were under a general open scrutiny.

It is not commonly recognized that some of Malcolm X.’s most acid attacks were made against Negroes. (“The sickest man needs the strongest medicine,” is how he explained this.) His flayings of various Negro figures, and organizations, and some prevalent customs were almost daily, but generally he confined this to Negro community audiences. He rarely spoke at a Negro College without flinging into the teeth of the faculty his criticisms of “the so-called educated Negroes.” He would say flatly, “You have not been in the vanguard of helping your poor, ignorant black brothers.” He decried the dearth of Negro knowledge of “the great history of the black race, extending back to antiquity. Why, if I was the president of this college, I’d hock the campus if I had to, to send students to the Black Continent to dig up more artifacts that prove our great history. You’re sitting here, and the white man is waking up—he’s digging. Why, it’s gotten so an African elephant can’t stumble without falling over some white man with a spade!”

Exposed to any relatively affluent Negro audience, Malcolm X. would score them for “not supporting” the Negro organizations. “You run to the surburbs. You don’t provide the help and leadership your poor brothers need, like the Jew does. However rich the Jew is, he never forgets his brothers still in the ghetto. If he can’t go and help personally, or send his wife, he at least donates money. But you won’t! That’s why the black man’s organizations are controlled by the white man today, because the white man supports them!”

Traveling about with Malcolm X., more than one time I saw him deliberately goad into anger various officials of the ranking organizations dedicated to Civil Rights. “—black bodies with white heads! The white man supports you and thus he controls you because he has your paycheck. The black man is the only group in this country who has allowed other people to be at the head of his organization!” I believe I am correct that of the major Negro leaders, the two whom Malcolm X. most admired—one openly and the other covertly—were Congressman Adam Clayton Powell and The Reverend Martin Luther King. Of Congressman Powell, Malcolm X. told me, “He hasn’t let Congress make him forget what it is to get out and organize on the streets. He knows that to change the black man’s situation, you’ve got to give him an example of standing up to the white man. Though Malcolm X. often took public digs on Dr. King, he told me “You’ve got to admire his coolness under fire. The only thing I wish is that his hero was some of the old labor leaders instead of Mahatma Gandhi. Look what changes King could bring! Look at how labor was being called scum, radicals and anarchists back in the Thirties, but look now, what’s happened because they weren’t non-violent. Today, labor has a lobby building overlooking the White House, and labor sits down with management and bargains as equals.”

Malcolm X’s criticisms among his own race ranged on one occasion to nearly physical assault. His car screeched to a stop one day as we drove along 136th Street, between Lenox and Seventh Avenues. Malcolm X. bounded and among about six huddled Negro teen-agers like an avenging devil. “You here shooting craps, and inside these doors whites your age are studying about you!” The teen-agers who were cowed thoroughly by the man they instantly recognized had been shooting dice against the doorway of the Countee Cullen public library branch which houses the great Schomberg Collection, the largest in the world of literature about and by Negroes. Malcolm X. was furious when he returned to the car. He said, “I just saw red when I saw that!”

Malcolm X. was deeply intrigued with centers of culture of any sort. He had a fetish for learning. Especially he favored museums, and several times we walked about in the Egyptian Room of the Metropolitan Museum. “I feel like I’m among my ancestors in here,” he said. “This is black art that predates Christianity by thousands of years. If I could do it, I’d have black schoolchildren in here every day, by the busloads.”

The eight-grade cessation of his own education probably was Malcolm X’s bitterest single reminiscence during his narrative of his entire life story. He had been an outstanding student in the Mason, Michigan, High School, where he was the only Negro in his class, and he was elected the class president. But a class counselor—who was fond of him—advised him to forget the desire he expressed to become a lawyer, and to become a carpenter instead. “I often think about this, I guess it was the most crucial point in my life,” said Malcolm X., as wistfully as he ever became. “He wasn’t against me, in fact he was thinking he was helping me, because all he could see was a black boy, not a mind that wanted to develop. If he hadn’t said what he did, I probably would have been a lawyer today. Because when I went to Boston, as badly as my sister Ella wanted our family to be somebody, why, Ella would have taken in washings if she’d had to, to get me in Harvard Law School and put me through there.”

The eventual additional education that equipped the Malcolm X. who brilliantly debated some of America’s top minds in communications and academic circles was gained through his years of reading as a convict in prisons. I think that some of the most intimate glimpses into himself that Malcolm X. ever presented were in the area of his yearning to be better formally educated. “You can believe me,” he says in the last chapter of his book, “if I had the time right now, I would not be one bit ashamed to go back into any New York City public school and start where I left off at the ninth grade, and go on through to a degree. … I would just like to study. I mean ranging study, because I have a wide-open mind … I do believe that I might have made a good lawyer, I have always loved verbal battle, and challenge ….”

I particularly remember the occasion of Malcolm X.’s telling me this. I had accompanied him to the Kennedy Airport where he took a jet to Los Angeles. Waiting for the plane’s departure, he had been talking about Shakespeare. “In my opinion, in ‘Hamlet,’ Shakespeare summed up this whole violence versus non-violence issue today,” said Malcolm X. “ ’To be or not to be, that is the question. Whether it is noble in the mind of man to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take up arms against a sea of trouble—’ ”

I remember that at 4 a.m. in the next morning, New York time, my telephone rang, wakening me, and Malcolm X.’s voice said “I trust you seventy percent,” and he hung up. It warmed me, knowing Malcolm X. (Neither of us ever again mentioned it.)

Malcolm X.’s attitude toward white people had begun to change within himself, I believe, well before his break came with the Black Muslim organization, or his subsequent trip to Mecca, which is generally identified with his alteration of previous racist views. I feel certain that what brought about the change was his cumulative direct contact with whites, chiefly in the communications fields, and in college and university audiences, who exhibited their respect for him as a highly intelligent individual, notwithstanding his anti-white statements. He said to me once what I knew was a highly significant statement from him, speaking of four radio or television program hosts whose shows he had returned to many times, Irv Kupcinet in Chicago and in New York Barry Farber, Barry Gray and Mike Wallace. “I like them because they let me see they respect my mind,” Malcolm X. told me. “The way I know that is they ask my opinion on subjects off the race issue. You see, most whites, even when they credit a Negro with some intelligence, never feel that Negro can contribute something to other areas of thought, and ideas. You just notice how rarely you will ever hear whites asking any Negroes what they think about the problem of world health, or the space race to land men on the moon.”

And I saw Malcolm X. hugely enjoying question-and-answer session give and take after college lectures too many times to ever accept that he nurtured a congenital white hatred. He loved to maneuver the white students into his standard verbal traps, then to sting them with his practiced arrows. “You took away our names, gave us your names. You hear somebody say ‘How are you, Murphy?’ Naturally you’re expecting a white man. What does some black man look like named Murphy?” He loved it when members of white student audiences stood up and managed to maneuver him into tight spots, where he had to call upon all of his arsenal of verbal dexterity to extricate himself. And the most familiar tight spot that I heard students get him into was queries, variously put, of how could he, with his mind, believe all of the things he said in the service of Elijah Muhammad? Generally, Malcolm X. would throw out a torrent of words. And I think that the time I ever saw Malcolm X. most “put down” in all of the two years that I knew him was after such a peroration of his in response to a question from a small, blonde-haired slip of a co-ed. When he finished, she stood up and said clearly, “Mr. Malcolm X., methinks you doth protest too much.” Malcolm X.’s mouth worked, but no words emerged. He quickly nodded to someone else who was waving a hand to ask a question. But the girl’s touché hung in the atmosphere, and he, and I, and everyone present knew it.

When I occasionally made trips involved in writing magazine assignments, Malcolm X., in open camaraderie now, would ask me always to telephone him when I would be returning to New York. If he could squeeze it into his schedule, he would meet me at the airport. And for my part, I always found myself anxious to return, for the whole sweep of the story of his life had become to me fascinating, and each next interview seemed to add some little extra.

Then once when I was thus returning, Malcolm X. asked me as we drove into New York, “Look, you get around—have you heard anything?”

I had no idea what he was getting at, and I said so, and instantly he shifted the subject, leaving me wondering. But I had learned never to press him on any issue. (Long before, some persistence of mine had prompted from him a sharp “If I want you to know something, I’ll tell you.”) I had learned that my best clue to whatever Malcolm X. had meant would likely reveal itself through his scribbling habit.

For months I had collected paper napkins, edges of newspapers, and other pieces of paper on which Malcolm X. compulsively scribbled as he talked, then left lying around. They had always given me clues to the stream of his thinking. Here are some examples: “Here lies a YM, killed by a BM, fighting for the WM, who killed all the RM.” (A decoding wasn’t difficult, knowing Malcolm X. “YM” was for yellow man; “BM” for black man, “WM” for white man, and “RM” was for red man.) Another: “The louder WM yelps, more I know I have struck a nerve.” Another: “BM took 2nd-class so long WM came to accept it as air he breathes.” Another: “WM so quick to tell BM ‘Look what I have done for you!’ No! Look what you have done to us!” Or “BM dealing with WM who put our eyes out, now condemns us because we cannot see.” Or, “If BM as successful building factories as churches, what a difference today!”

I did not have to wait long before my clue came. On a paper napkin served with coffee, Malcolm X. scribbled, “My life has always been one of changes.”

I knew that Malcolm X. had something in mind that was of major consequence to him. But my wildest speculation would not have anticipated what was about to happen.

It is generally well-known that Elijah Muhammad publicly announced the suspension of Malcolm X. for his having made the statement that he viewed the assassination of the late President J. F. Kennedy as “chickens coming home to roost.”

Talking with me about it later, Malcolm X. ranged between bitterness and fury, which he managed to keep reasonably guarded in most of his public utterances. “I’ve been a street hustler,” he said, the back of his neck and his whole faced flushed reddish with his anger, “I know when I’m being set up. I’ve said plenty of hotter things than that, and Chicago never objected. And look how the press jumps on me when every commentator in the country has said the same thing I said. Or take that book of Victor Lasky’s—it has been called outright lies about Kennedy, but they made his book into a best-seller!”

Suspended from any public appearances or from any utterances in the name of the Black Muslims, Malcolm X. chafed at the bit, and it was in this time that he and his wife, “Sister Betty” and their then three children were invited by Cassius Clay to his Miami training camp for the first fight against Sonny Liston. Malcolm X. later told me that he was most grateful—it was something to do. He and Clay had met over a year before in Detroit, and Clay had become one of the few Muslims whom Malcolm X. had ever accepted as a close personal friend. Several times he had spoken of Clay to me with a warmth rare for Malcolm X. I got postal cards from Malcolm X. in Miami, and in one telephone call he told me “I’m not a betting man, but if you are put some money on Cassius, and you can get rich.” I read in the papers that Malcolm X. was functioning as Clay’s “spiritual advisor.” I heard from a friend in Miami that the two had daily walks after Clay’s training day was over. Then, the night of the gigantic upset, Malcolm X. telephoned me, his voice all but crowing, “What did I tell you?” He said that it had been probably the quietest new-champion party in history, that at that moment “Champion Cassius” was asleep on his (Malcolm X.’s) bed, “catching a nap.”

Soon, Malcolm X. was squiring Clay about in New York at the United Nations and other places. I saw Malcolm X. but little during this time, but he sounded happy in his role when we talked on the telephone. Then, abruptly, something caused Clay to reject Malcolm X., transferring his total allegiance to Elijah Muhammad. I believed that the most hurt that I ever saw Malcolm X. revealed to me—aside from his suspension by the Black Muslims—was regarding Clay. “I felt like a blood big-brother to him,” he said slowly. And carefully considering the words in advance, “I still do. I’m not against him. He’s a fine young man. Smart. He’s just let himself be used—led astray.”

Malcolm X. next went to Mecca where he performed the Hajj Pilgrimage, and after visiting in some of the emerging African states, he returned to America, presenting himself as now a true orthodox Moslem. Almost with shock, I had received the letter he had written me on blue stationery containing the words so incredible for Malcolm X.: “—During the past eleven days here in the Muslim world, I have eaten from the same plate, drunk from the same glass, and slept in the same bed (or on the same rug)—while praying to the same God—with fellow Muslims, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond, and whose skin was the whitest of white, and we were truly all the same (brothers) . . . ”

Another copy of the letter had been published across America. And Malcolm X., now calling himself “El Hajj El Malik El Shabazz,” entered now, when I reflect upon it, the final trail of problems and harassments that would plague him to his death.

From the first stages of his interviews, he had spoken often about his anticipation of a violent death. “All of my father’s brothers but one died violently,” he had said. “I never expect to live to be an old man.” Now, when the first death threats to him were publicly reported, one day in the Americana Hotel he leaned forward and touched the bed. “If I’m alive when this book is published, it will be a miracle,” he said. “I’m not saying that in any distress. I’m just saying it like I say that’s a bedspread.”

Angered and goaded, Malcolm X. began to speak bitterly and accusingly in public about the “immorality” of Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm X. told me once in strictest confidence that he had been to a doctor in Long Island and asked for a brain examination, fearing for his sanity, because the shock of his “betrayal” by the Muslim leader had been so great. Later, Malcolm X. said, “You can go ahead and use that in the book, I want it to be the whole story.”

Causing Malcolm X. not much less worry was the establishment of the new public image that he wanted. He had formed two new organizations, a “Muslim Mosque, Inc.”, religious in nature, and an “Organization for Afro-American Unity” which offered a Black Nationalism program. But both whites and Negroes were either flatly disbelieving that Malcolm X. was any different in his beliefs, or they were confused about what he now believed. There is more than a little reason to believe that Malcolm X. himself was confused. “I am man enough to admit that I can’t put my finger on exactly what my philosophy is now,” he told one writer in an interview not published until after his death. “But I’m flexible.”

At Kennedy Airport, waiting with me for my plane to an upstate New York city, Malcolm X. told me how he was finding that the “so-called moderate” civil-rights organizations were avoiding him as “too militant” and the “so-called militants” shunned him as “too moderate.” He exclaimed, “They won’t let me turn the corner! I’m caught in a trap!”

When I left Malcolm X. there to drive out of the parking lot when I went to catch my plane, we waved at each other—and it was the last time I would ever see him alive.

The “trap” that Malcolm X. was in kept closing around him tighter. He telephoned me upstate, telling me that the court had ordered him to be evicted from the home which he had occupied for years: the home legally belonged to the Black Muslim organization, which had successfully sued for its return. “My nerves are shot—my brains tired, Haley,” Malcolm X. said, the first time I had heard him ever say anything like that. He said I had spoken of the quiet town where I lived; he asked if he might visit for a weekend. “Just a couple of days of peace and quiet, that’s what I need.” He said that he would like to read through the full book manuscript once more. I said that he knew he was most welcome to visit, but he shouldn’t tax himself with another reading as only very minor editing changes had been made in the manuscript since he last read it. He said “I just want to read it again. I don’t expect to be alive to read the finished book.”

The weekend that Malcolm X. said he would like to come and have a restful visit was, ironically, the Saturday and Sunday of 21-22 February, 1965. The subsequent bombing of his home, and myriad other nerve-wracking complications threw his plans so askew that he couldn’t make it. He telephoned me once again, that Saturday afternoon. He said he had only $150 and he wondered if the publisher could advance him a down payment for a new home for his family. “You know nobody will rent, not to me!” he tried to chuckle. I said I would have our agent check on Monday, and I would telephone him back Monday night.

But on Sunday afternoon, the killers got to Malcolm X. as he started to speak to an audience in the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. There ensued a week of the greatest news coverage of a death that America had seen since the assassination of a beloved young President. I went and I looked down upon the waxy, dead face surrounded by linen Moslem burial dress. All I could seem to think was “Well—goodbye, Malcolm!” And a policeman on guard motioned for me to move on, and I did. ~ Alex Haley.

(The Malcolm X I Knew is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was published in the November 1965 issue of Saga. © 1965 Saga. All Rights Reserved.)