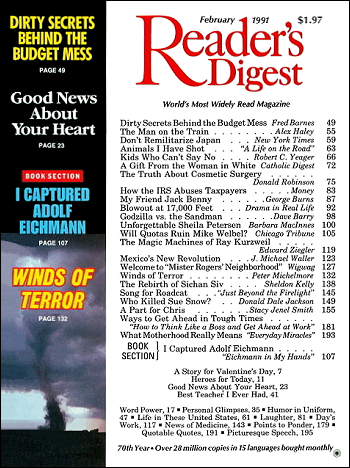

(The Man On The Train by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1991 issue of Reader’s Digest. In 2007, Reader’s Digest republished the article in Alex Haley: The Man Who Traced America’s Roots.)

(The Man On The Train by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1991 issue of Reader’s Digest. In 2007, Reader’s Digest republished the article in Alex Haley: The Man Who Traced America’s Roots.)

Though some people may attempt to live life from a purely selfish, self-centered perspective, it is in giving of ourselves to others that we find our greatest sense of meaning. And so, as we search for meaning, one of the best places to look is outward—toward others—using the principle of charity.

Too often the meaning of charity is reduced to the act of giving alms or donating sums of money to those who are economically disadvantaged. But charity in its purest forms involves so much more. It includes the giving of our hearts, our minds, and our talents in ways that enrich the lives of all people—regardless of whether they are poor or rich. Charity is selflessness. It is love in work clothes.

Alex Haley’s father, Simon Alexander Haley, worked his way through college and graduate school as a Pullman porter until he met The Man On The Train. Always, Haley seems to be telling us, opportunity awaits those who are prepared.

A poignant example is found in the story of The Man On The Train. Recalled by distinguished and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alex Haley, it is the true story of a man Alex never met, but one to whom he came to give great honor and credit.

In addition, Haley also shares why he broke down in tears when he first visited the offices of a famous newspaper. As you read his account, resist the temptation to reduce the story to that of a kind man offering a handout.

The Man On The Train

Whenever my brothers, sister and I get together we inevitably talk about Dad. We all owe our success in life to him—and to a mysterious man he met one night on a train.

Our father, Simon Alexander Haley, was born in 1892 and reared in the small farming town of Savannah, Tennessee. He was the eighth child of Alec Haley—a tough-willed former slave and part-time sharecropper—and of a woman named Queen.

Although sensitive and emotional, my grandmother could be tough-willed herself, especially when it came to her children. One of her ambitions was that my father be educated.

Back then in Savannah a boy was considered “wasted” if he remained in school after he was big enough to do farm work. So when my father reached the sixth grade, Queen began massaging grandfather’s ego.

“Since we have eight children,” she would argue, “wouldn’t it be prestigious if we deliberately wasted one and got him educated?” After many arguments, Grandfather let Dad finish the eighth grade. Still, he had to work in the fields after school.

But Queen was not satisfied. As eighth grade ended, she began planting seeds, saying Grandfather’s image would reach new heights if their son went to high school.

Her barrage worked. Stern old Alec Haley handed my father five hard-earned ten-dollar bills, told him never to ask for more and sent him off to high school. Traveling first by mule cart and then by train—the first train he had ever seen—Dad finally alighted in Jackson, Tennessee, where he enrolled in the preparatory department of Lane College. The black Methodist school offered courses up through junior college.

Dad’s $50 was soon used up, and to continue in school, he worked as a waiter, a handyman and a helper at a school for wayward boys. And when winter came, he’d arise at 4 a.m., go into prosperous white families’ homes and make fires so the residents would awaken in comfort.

Poor Simon became something of a campus joke with his one pair of pants and shoes, and his droopy eyes. Often he was found asleep with a textbook fallen into his lap.

The constant struggle to earn money took its toll. Dad’s grades began to founder. But he pushed onward and completed senior high. Next he enrolled in A & T College in Greensboro, North Carolina, a land-grant school where he struggled through freshman and sophomore years.

One bleak afternoon at the close of his second year, Dad was called into a teacher’s office and told that he’d failed a course—one that required a textbook he’d been too poor to buy.

A ponderous sense of defeat descended upon him. For years he’d given his utmost, and now he felt he had accomplished nothing. Maybe he should return home to his original destiny of sharecropping.

But days later, a letter came from the Pullman Company saying he was one of 24 black college men selected from hundreds of applicants to be summertime sleeping-car porters. Dad was ecstatic. Here was a chance! He eagerly reported for duty and was assigned a Buffalo-to-Pittsburgh train.

The train was racketing along one morning about 2 a.m. when the porter’s buzzer sounded. Dad sprang up, jerked on his white jacket, and made his way to the passenger berths. There, a distinguished-looking man said he and his wife were having trouble sleeping, and they both wanted glasses of warm milk. Dad brought milk and napkins on a silver tray. The man handed one glass through the lower-berth curtains to his wife and, sipping from his own glass, began to engage Dad in conversation.

Pullman Company rules strictly prohibited any conversation beyond “Yes, sir” or “No, ma’am,” but this passenger kept asking questions. He even followed Dad back into the porter’s cubicle.

“Where are you from?”

“Savannah, Tennessee, sir.”

“You speak quite well.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“What work did you do before this?”

“I’m a student at A & T College in Greensboro, sir.” Dad felt no need to add that he was considering returning home to sharecrop.

The man looked at him keenly, finally wished him well and returned to his bunk.

The next morning, the train reached Pittsburgh. At a time when 50 cents was a good tip, the man gave five dollars to Simon Haley, who was profusely grateful. All summer, he had been saving every tip he received, and when the job finally ended, he had accumulated enough to buy his own mule and plow. But he realized his savings could also pay for one full semester at A & T without his having to work a single odd job.

Dad decided he deserved at least one semester free of outside work. Only that way would he know what grades he could truly achieve.

He returned to Greensboro. But no sooner did he arrive on campus than he was summoned by the college president. Dad was full of apprehension as he seated himself before the great man.

“I have a letter here, Simon,” the president said.

“Yes, sir.”

“You were a porter for Pullman this summer?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Did you meet a certain man one night and bring him warm milk?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, his name is Mr. R. S. M. Boyce, and he’s a retired executive of the Curtis Publishing Company, which publishes The Saturday Evening Post. He has donated $500 for your board, tuition and books for the entire school year.”

My father was astonished.

The surprise grant not only enabled dad to finish A & T, but to graduate first in his class. And the achievement earned him a full scholarship to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

In 1920, Dad, then a newlywed, moved to Ithaca with his bride, Bertha. He entered Cornell to pursue his master’s degree, and my mother enrolled at the Ithaca Conservatory of Music to study piano. I was born the following year.

One day decades later, editors of The Saturday Evening Post invited me to their editorial offices in New York to discuss the condensation of my first book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I was so proud, so happy, to be sitting in those wood-paneled offices on Lexington Avenue. Suddenly I remembered Mr. Boyce, and how it was his generosity that enabled me to be there amid those editors, as a writer. And then I began to cry. I just couldn’t help it.

We children of Simon Haley often reflect on Mr. Boyce and his investment in a less fortunate human being. By the ripple effect of his generosity, we also benefited. Instead of being raised on a sharecrop farm, we grew up in a home with educated parents, shelves full of books, and with pride in ourselves, My brother George is chairman of the U.S. Postal Rate Commission; Julius is an architect, Lois a music teacher and I’m a writer.

Mr. R. S. M. Boyce dropped like a blessing into my father’s life. What some may see as a chance encounter, I see as the working of a mysterious power for good.

And I believe that each person blessed with success has an obligation to return part of that blessing. We must all live and act like the man on the train. ~ Alex Haley.

(The Man On The Train by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the February 1991 issue of Reader’s Digest. © 1991, 2007, 2013 The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)