Alex Haley, the author of Roots, recalls his Southern boyhood—when he learned the meaning of family tradition—and offers ways you can bring your own kin closer together. A quote from Family: A Humanizing Force:

Alex Haley, the author of Roots, recalls his Southern boyhood—when he learned the meaning of family tradition—and offers ways you can bring your own kin closer together. A quote from Family: A Humanizing Force:

“What we have now is an urgent need to collect as much of the oral history that remains as we possibly can. The greatest part of the history of this country is in the memories and minds of older people. Every year in this country about two million people who are sixty-five or older pass away, and with them goes a great big chunk of this country’s history. That history is irretrievably lost unless those older people have been interviewed and their memories recorded by members of their family or others who are interested. We are now in a position to do something about family histories.

“Apart from collecting our family histories, one of the most important things we can do, I believe, is to spread as widely and as intensively as we can the idea that we should try to hold family reunions, much, much more than we have tended to hold them.

“The family is the building block of society, and every time a family meets, that particular building block is solidified. Reunions do magical things within the family itself; they do equally magical things within the component of society of which that family is a part. It is exciting no end to think what worldwide family reunions might, in fact, contribute toward worldwide peace. There is no active world war which could conceivably be so exciting as an active world peace. If we could do these things, we would reach toward that utopia of which I have spoken. Utopia for us human beings may be asking too much, but peace is not asking too much; it is in our grasp…” ~ Alex Haley

Alex Haley: The Secret of Strong Families

I was only four years old, and so nobody told me the mysterious look I sometimes saw my Mama and Dad exchange in our little church on Sunday mornings had anything to do with that word “love.” During those long-ago Sunday mornings, I’d be seated in the front pew beside my Grandma, and my Mama would be tip alongside the choir at the piano. She’d be playing some opening bars, but without looking down at her fingers on the keys because she’d be gazing straight across the piano’s top at my Dad who would be standing waiting to sing. His head would be turned just enough to look straight back at Mama, and as I watched, their looks would seem to fuse.

Every time they shared that particular look, it seemed to me so strong that somebody could just reach out and touch it. It also seemed clear they didn’t care that the whole congregation was seated right before them, watching. I wasn’t entirely sure if I should feel embarrassed about how they were acting up there. They were so close to our preacher seated in his pulpit in his big wing-backed, brown leather-covered chair.

And then Mama would strike a certain chord, and Dad would quickly turn his head and, smiling out at our congregation, start singing his baritone solo. I know one thing today, over fifty years later: That image of my Mama and Dad gazing across the top of the piano at each other remains for me synonymous with a man and a woman truly loving one another.

I have another image I carry from that time when I was growing up in my little hometown of Henning, Tennessee. I remember watching a strange thing that went on at our dining room table when Grandpa would say the prayer before we’d eat our meals. In our 1930s Bible Belt South, neither our family nor, I guess, any others—black or white, that considered themselves decent—would ever think of eating any meal which hadn’t first been prayed over by the head of the house. In our family that was Grandpa, although he would sometimes delegate to Dad with a quick glance or a nod.

But the thing that the little boy who was me found so bemusing was that always when nearing the end of the prayer, Grandpa would say, “And, please, O Lord, bless the hands that prepared this meal.” I just couldn’t help squinching open one eye and peeping across the tablecloth at Grandma’s hands, so as not to miss if the Lord might decide to bless them right then! But always Grandma just sat as if she were carved, her graying bead bowed over her wrinkled hands. On one of those loosely-clasped fingers was her worn gold wedding band about which she liked to say, “Ain’t never been off since Will stuck it there.”

I’d wonder how Grandma must feel when she’d be out in the kitchen using those hands to cook with, knowing that the Lord was soon going to be asked to bless them. And I hoped that if He would, that He’d also bless mine, so I’d know how something as powerful as that would feel. Anyhow, when any food blessing prayer ended, we’d eat and I’d feel once again there within our home a second variety of that word “love,” which somehow this time seemed to me even more solemn and sacred.

During some portion of each summer, my Dad would catch a train and ride off up North to a Cornell University that was in an Ithaca, N.Y., to study some more toward obtaining what he’d often proudly tell people would eventually be his “master’s degree.” I didn’t understand what such a degree was. Neither did most of the people in the town. Finally our church’s good sister, Miss Scrap Green, figured it out for herself and made it her business to tell everybody that the meaning was “ ’Fesser Haley’s just takin’ all the educatin’ that any one man’s head can stand.” Her explanation kind of settled that matter for most of our Henning people.

Anyhow, during those periods when Dad was gone off up North to do his studying, another memorable thing would happen. With Dad not there to help him, Grandpa generally got home much later than usual from his Will E. Palmer Lumber Company. Sometimes when he got home he’d say to Grandma that there was someone he needed to see before it got dark. I’d be hanging around practically under their feet, and always they’d frustrate me by acting as if I were nowhere in sight. But then Grandpa would give Grandma, or Mama, an exaggerated questioning look. If they nodded back, it meant that I’d acted pretty fair that day. Then Grandpa, with still not a glance at me, would just thrust down his right hand extending stiffly its big index finger. I’d jump like a watch spring to clutch it tightly within my fist. And we’d leave the house with Grandpa striding and me struttin’. I would be so happy and proud.

Grandpa was real black and he walked tall and erect. As we progressed, I’d sometimes look down at our feet and count silently to myself how it was taking three of my short, quick steps to keep up with his long, slow one. I remember that each step he took sent one of his pants cuffs jerking backward over one of his dully-shined, black hightop shoes, then just as that foot would set down, the other foot would have swung forward over the usually dusty footpath.

And somehow after we’d gone a pretty good distance with me steadily holding onto Grandpa’s forefinger, I’d begin having a feeling that kind of resembled my Mama’s and Dad’s fusion of gazes. It would feel like something was flowing from deeply within my Grandpa and through has finger into my fist and on down within me. And an image would start up in my head, that Grandpa was our family’s tall, strong tree. My Dad, Grandma and Mama each were stout limbs on it, while obviously I was still just a twig. But at least I knew that every day I was eating all that I could hold, trying my best to grow as strong and as big as I could.

Finally, let me share one further incident from my boyhood there in Henning. It remains for me so indelible, principally because at intervals ever since I’ve continued to realize with new insights and new gratitude how hard my family, a loving, protective Southern black family, tried to rear me in a positive manner. It wasn’t easy in that time, amid the intense racial prejudices of the 1930s, which were at their most overt, of course, in the South. Anyway, I was still four and my forthcoming fifth birthday had me very excited. I was very anxious to get older, although that situation had been helped because I had a baby brother named George. Since his arrival I had seized every opportunity to observe to whomever I could that I had become a “big brother,” which somewhat elevated my status.

But during the days immediately preceding my birthday, my frustration had steadily mounted because I somehow simply knew I’d soon be receiving some sort of big birthday present. I especially sensed this from my elders who had begun acting as if they were unaware that I even existed. I did my very best discreet searching within the house, both upstairs and down, and found absolutely nothing, whereupon I launched into my very best wheedling efforts for even any little hint, but that didn’t get me anything more than my poor elders’ blank, deadpan expression.

Awakening and bursting from the bed and snatching on my clothes, I fairly flew downstairs before breakfast on that August 11th morning. I met four impassive adults who then began walking solemnly out onto the back porch, clearly meaning that I should, as I did, follow, falling in behind Grandma, who was carrying baby George. Our little procession had crossed the backyard when I noticed Grandpa’s Model-A Ford truck was parked by the cowbarn instead of its usual spot inside the garage, whose door now bore a shiny big new iron lock.

My Dad unlocked and swung wide open the garage door. Astonished, I saw a maybe foot-thick tree slice leaning up against a wall. It stood wider than I was tall, and had maybe twelve to fifteen round, white markers stuck on here and there, each bearing some small handprinting. I stood staring at it, wondering what on earth some tree slice could have to do with my birthday, when my Dad began pointing and explaining how each year a tree acquired one more of the clearly visible “annual growth rings,” and this tree’s many rings meant it had been cut down after growing for nearly 200 years. Then Dad told me how each one of those round, white markers represented how big and how old that tree was when whatever was printed on each marker happened.

Pointing out a marker that was positioned deep within the tree slice, Dad said that one represented—and it was the first time I ever heard the words—”the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves.” It was still confusing, even though I’d heard Grandma speak a whole lot about “slaves.” She had often told me that her parents, then their parents, and plenty more before them, too, living away back in time, had been slaves working on plantations for white people who had owned them. What confused me was that I just couldn’t understand how any person could go around owning other people.

Another marker represented the founding year of Lane College, in Jackson, Tennessee, where I’d heard countless times that Mama and Dad first met when he’d asked to walk her back to her dormitory after a choir practice. Another familiar Lane College story was that when Dad and Mama got married, Grandpa, sparing no expenses, had phoned the Lane College president and paid for the college choir to ride in a bus to Henning where they sang at the wedding.

Yet another marker showed how big and how old that tree was in the birth-year of my famous rooster-fighter great-grandpa. Although he was a slave, he was known and respected wherever he went as “Chicken George,” and Grandma loved to tell stories about him. Some markers were for people of whom I’d never heard, like a Harriet Tubman, a Frederick Douglass and a Sojourner Truth, for instance. Dad told me they were important persons I’d be needing to learn a lot more about. And there were other birth-year markers representing Grandpa, Grandma, Dad and Mama—and even me. And I remember how strange I felt, looking at the marker of when I’d entered the world, because it was placed at just five years of those growth rings, practically right beneath the tree’s bark!

Looking back on that August morning, I can see my parents’ and grandparents’ reasons for giving me that singularly imaginative gift for a fifth birthday. For one, they wanted me to have a useful perspective on history, and they also wanted to start broadening my vistas. Concurrent with those aims, their intention was to start—that early—shielding me the best they could against the racial harshnesses I’d inevitably meet. Young black person suffered most when they were not girded in advance with some knowledge of their ethnic past coupled with pride in being black—or “colored,” as was the ethnic term used at that time. My Dad later told me that often when I slept, the four of them would sit and discuss such concerns for hours, and that after Mama presented the tree slice idea, the actual thick cross-section of a California redwood was obtained by Grandpa through his lumberyard connection, but just barely in time for my birthday.

For me, I know that a tree slice, a symbol of a family’s concern and love, certainly did implant my boyhood concept of history as a drama of people, some gone, others living, and of events as real as any in the present but which had actually happened during the past. And I know that my tree slice gift had the further effect of getting me to read all the books that I could as my desire grew to find somebody else worthy of yet another marker’s placement, preferably away down within the tree slice. Most of my suggestions (such as Cinderella!) didn’t qualify, but now and then something would, and my pride swelled. Before I reached age six, no one visiting us escaped my using my cut-down teacher’s pointer in explaining all about trees’ annual growth rings, then what each of my eventually fifty or more markers represented. As I sit here remembering this, I’ve no question that my fifth birthday’s tree slice set into motion a whole long interrelated chain of events which turned me into a writer who prefers historical subjects.

Certainly it is this habit of looking at things with a historical perspective that makes me realize that in today’s advanced society too many of us are losing our once-strong family ties, such as those I had as a boy in Henning. The symptomatic sounds of our loss are already familiar. Two pervasive examples are the common expressions, “I’m trying to find myself,” or, “I need my own space.” Whether these popular statements are made in a tone conveying matter-of-factness or sophisticated élan, to me the bottom-line translation is rootlessness. And also, a word that bothers me is “relationship,” popularly applied across the whole range of human unions. To me it seems to avoid stating solid commitment, a fact reflected in today’s unprecedented divorce rate. (Pray forgive my flashback to the most moving words I think I ever heard my Grandma utter. One evening during her last years, with Grandpa long dead, she sat quietly listening to several of us family members discuss new sexual mores, then abruptly she offered, “Ain’t never knowed no man but Will.” Thinking about it, I later wept at its simple majesty.)

Today I believe that we must pursue ways to rebuild our families, which may have eroded during the swiftly changing past years. We must recapture the values that interacting, interdependent, loving families once had. And I also believe that there are specific ways families can indeed strengthen themselves. For instance, while I’m a fourth-generation Methodist, I believe that any family will benefit by adopting the weekly tradition known as “Family Night” which is widely practiced by Mormons. Family members set aside an hour one night every week to get reacquainted with each other and to work and pray together and exchange candid views. Mormon bookstores usually carry a booklet, called Family Time, which is filled with concrete suggestions on how to spend that hour together. A characteristic gathering might see the family talking about traditions and how they were started or parents telling youngsters about their own childhood experiences. Group discussion of a recent movie or television show can richly fill an evening hour together as well. Finally, Family Nights end with a prayer of thanks for the gathering.

Another good way to strengthen a family is to research its history. This is best accomplished when youthful family members query elders and pursue the nigh-mystical interrelations of the past and the present. For some reason, grandparents and other aged folk will tell their own children far less than they will reveal to their grandchildren.

Attics of old family homes should be searched. Precious treasures are probably lying in wait. (Imagine me the morning I blew dust off what turned out to be my ex-slave great-grand father Tom Murray’s ledger of his charge account as a free blacksmith.) Don’t overlook any packets of letters. My most cherished old letter was Grandpa’s written proposal to Grandma, herewith literally: “Dear Cynthia: We have been keeping company for two years. I feel it is now time we should discuss the contract of marriage. Yours sincerely, Will E. Palmer.” Later, Grandma confessed to me that upon receipt of that letter, she, in her words, “went tearing out all through the house, hollerin’ to my Mama and sisters, ‘I got him! I got him!’ ”

Finally, nothing strengthens a family more than a planned reunion. Something almost mystical happens when numerous and widely-dispersed family groups converge somewhere en masse—and are suddenly a clan.

For all the thrills that happen during a reunion, I believe the most emotional moment of all is when the professional photographer starts arranging for the formal full-family portrait. Classically, all front-row steps are reserved for those of the eldest generation. Would you like to test you capacity for tearfulness? Then you just stand quietly watching as some two young members each gently takes an arm and starts carefully guiding an elder whose vision wavers now, whose footsteps falter, to a front seat.

Next, your clan’s newest members are set into those elders’ laps. Likely your tears will freshen, looking at sagging, aged ones clutching the lively, plump babies—and you realize that probably you will never again witness that particular pair occupying that seat of honor in that graphic generational contrast.

When at last the camera clicks, the resulting photograph will capture, at least for a moment, your clan, which is unique on this earth. With that experience and that photograph as evidence of the generational ties, every family involved can scarcely miss feeling a wellspring of new strength. ~ Alex Haley.

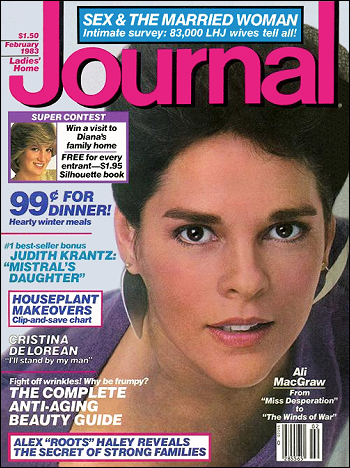

(Alex Haley: The Secret of Strong Families is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published within the February 1983 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal. © 1983 Meredith Corporation Inc. All Rights Reserved.)