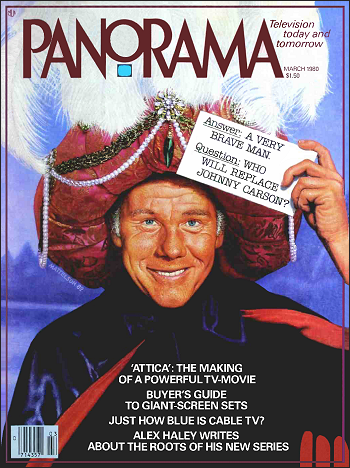

(Chasing Rainbows Memories of a Southern Boyhood by Alex Haley was published in the March 1980 issue of Panorama TV Magazine)

(Chasing Rainbows Memories of a Southern Boyhood by Alex Haley was published in the March 1980 issue of Panorama TV Magazine)

The first time I heard about Roots was at a three-hour lunch with Alex Haley, producers Stan Margulies and David Wolper, and Lou Rudolph, who worked for me at the time. I was in charge of ABC’s miniseries, movies and novels for TV, and, when Alex talked about his story, I really felt it was something we should do.

The book didn’t yet exist, but I felt that the essence of Roots would go way beyond just the black experience, and that it would be able to touch white, green, yellow, orange, red or blue families as well. It was a distinctly American story whose primary theme was the inalienable dignity of man, and based on that—and not on its ratings potential—we went ahead with Roots.

I was really bewildered by what happened. I just didn’t understand it, and I don’t think anybody did. I think the truth of it is almost mystical: Roots was an idea that simply was not going to be denied. But I didn’t anticipate that the show would experience that kind of success.

My reaction was much more related to confusion than to ecstasy and joy. In retrospect, the fun of Roots was the process of making it, which was enormously exciting. The week it was shown just wasn’t that much fun for me. I was so tired that at a dinner party at the Bel-Air Hotel, I fell asleep in a bowl of pea soup. ~ Brandon Stoddard, ABC Executive and President of ABC Motion Pictures.

Kings of the Hill is a new series, created by Alex Haley and Norman Lear, about two boys—one white, one black—growing up in the South of the Thirties. The author of ‘Roots’ describes how a chance meeting with Norman Lear led to a TV series rooted in their nostalgia.

Chasing Rainbows … Memories of a Southern Boyhood By Alex Haley

We all grew up somewhere, and most of us remember and treasure our home-town childhood experiences much more than we recall many later events of our lives. My own boyhood years were spent in Henning, Tenn., whose population of about 550 people, farming families predominating, made it fairly typical of the Southern small towns of the 1930s. Fifty miles north of Memphis, along the asphalted Jeff Davis Highway, Henning was one of the regular stops for the trains of the Illinois Central line, which ran between Chicago and New Orleans.

I’m sure that most of the travelers glancing about as they passed through Henning would think that our town was Dullsville compounded, but the fact was that we, the citizenry, felt quite the opposite. Just for starters, everyone living for any period of time in our town not only knew everyone else, but also knew some plausible merger of fact and gossip about their lives. And rarely a day would pass without some of the townsfolk, both white and black, acting out one of our local dramas, which ranged from the somber to the titillating. And whoever might have missed any of the details knew exactly whom to visit, since certain individuals fulfilled a function in our town rather like that of the Associated Press.

Well, one evening about a year ago, I attended a social affair in Beverly Hills where someone introduced me to Norman Lear. Almost immediately, we found ourselves reminiscing about our boyhoods; his had been spent in New Haven, Conn. We agreed we’d had such fun that, upon occasion now as adults, we wished we hadn’t had to grow on up. And before long we had decided that we ought to collaborate in producing a television dramatic series featuring the growing-up years of two boys—one white, one black—just like ourselves.

But a dramatic series would need to depict human conflicts that generated tension and built to a climax. Moreover, it would require a basic long-range premise, and though our episodes’ stories would be fictional, we wanted them to have the strength of atmospheric authenticity.

I told Norman of an experience I’d had in Henning as a boy that, in its way, interwove all of these criteria. From earliest remembrance, I’d run and romped about town with a close buddy, a little white boy slightly older than I, whose family lived just a diagonal stone’s throw across the dirt road from us. We played in each other’s yards and homes, our mothers fed us together, made us take naps together, spanked us for having done whatever mischief together, and so on. And it went along like that for some years, until one day my buddy and I were talking about his upcoming 12th birthday and he said quite casually, “Before you know it, I’ll be old enough you’ll have to call me ‘Mister’.” It’s a remark I will never forget.

I knew my buddy wouldn’t deliberately hurt me. Yet, in some deep and inexplicable way, he had. Neither of us could have realized at that time that the statement was not so much his as it was an articulation of the traditional Southern code under which we were all living—he, I and everyone else in Henning. I just remember that, right after that day, I avoided playing with him or even seeing him any more than I had to, with only a street between our homes; and whenever we did have any kind of contact, he seemed as confused and perplexed as I was confused and hurt. Within a matter of a few months, my former buddy and I had slid into our respective worlds of white and black. When I go to visit Henning now, some 40 years later, my inquiries about his family produce only the bare fact that they moved not long after he enlisted as a soldier in World War II, and no one seems to have heard from them since.

Norman and I agreed that that poignant experience contained the basic long-range premise we needed: a black/white close boyhood friendship that the surrounding adult world’s social mores eventually would corrode and destroy when the boys approached puberty. It is an experience that hundreds of thousands of youngsters of different races have known.

I wrote a pilot presentation, on the basis of which CBS agreed to underwrite an initial two-hour television movie, followed by six one-hour episodes, after which the viewers’ rating-response would determine whether or not we would have a continuing series. Titled Kings of the Hill, the series would be built around the two boys, their families, and the townspeople of both races in the imaginary Palmerstown, Tenn. (My middle name is Palmer, and that’s what I was called as a boy.) Our presentation to the network promised that each episode would portray a dramatic slice of 1930s Southern life, which was dominated by the code of segregation. Human dramas did indeed proliferate there, some ugly, others beautiful. The episodes would show how segregation gave rise to countless contradictions, complexities and ironies in an environment where white people and black people were in fact totally interdependent.

Our casting search began with the boys. We wanted them to be about 9 years old, which would enable us to show the friendship at its best—before the erosion that was to come. More than 4000 Southern schoolboys, black and white, were auditioned for the two parts. Finally selected were fourth-grader Brian Wilson, 11, of Mobile, Ala., to play the white David Hall; and a third-grader, Jermain Johnson, 9, of Houston, Texas, to play the black Booker T. Freeman. Then their families were cast. Grocer W. D. Hall is played by Beeson Carroll, with Janice St. John as his wife Coralee, and Michael Fox as David’s brother Willy-Joe, 15. Luther Freeman, the blacksmith in Palmerstown, is played by Bill Duke, his wife Bessie by Jonelle Allen, and their 14-year-old daughter Diana, Booker T.’s older sister, is played by Star-Shemah Bobatoon.

It is the mischievous escapades of the two boys that draw them into the lives of the local townspeople. Norman Lear and I, and others who sit in on our story-creation sessions, have pulled most of these tales out of our own childhood memories. There is one particular story that I will sit before my television set and watch with keen personal nostalgia—”The Lesson,” it is titled, and I was about 10 when an old lady in Henning told it to me. She said that her widowed, sharecropping mother was so poor that all she owned was a few chickens, among which one hen was hatching a clutch of eggs. Her mother gave her one of the hatching eggs, marked with an “X,” as a birthday present. After 40-odd years, I still remember tingling with excitement as the old lady shared her memories of that gift. The baby chick that hatched from the egg was the first thing she had ever owned, the first thing she had cared for. From it she learned a great lesson about life and about loving. That story, with dramatic embellishments worked into it, is the focal point of one of our early episodes.

There is another story that originated with the memory of a Henning elder. Shortly before World War I, the town was baseball crazy and had two teams, one white, one black, which segregation decreed would never play each other. But somehow the white team’s manager agreed to a game with a traveling black team, with a sizable bet involved. Then he discovered that the blacks actually were semi-pros. Fearful of losing the large bet, the manager prevailed on local civic leaders to suspend the rules of segregation and to urge the town’s best black players to join a mixed team that could face the challengers. This story, which we are calling “The Black Travelers,” is told in two episodes.

In the Bible-belt South where our series is based, the segregated churches played a central role in their respective racial communities. We have an episode that is drawn from one of the most emotionally moving church ceremonies that I ever witnessed as a boy. Surrounded by an atmosphere that is charged with suspense and tension, a church in Palmerstown will raise an aged woman to the locally exalted title of “Old Sister,” in recognition of her lifetime of extraordinary community service—an honor that in my home town was accorded to but a very few women within a decade.

Kings of the Hill will have a lot of the outdoors. David and Booker T. romp through fields together, get soaking wet in the rain, flatten out on their bellies to drink from the natural springs, hide in the weeds, find delightful patches of ripening cantaloupes and watermelons, and pick wild berries and cherries and sell them—along with empty whiskey bottles—to earn spending money. They study their lessons, build crystal sets, go to Sunday school, and in their respective churches witness baptisms, weddings and funerals, with only the viewers realizing that the boys in their little town are being taught the rites of passage.

Along with predictions that we may anticipate a successful series, there are also warnings from some quarters that viewers may find our episodes “too soft.” Obviously we are gambling, as is CBS, that today’s television contains enough “hard shows” and “formula shows”—that out there are a great many people who will enjoy a human drama that evokes the days when they too romped and ran and chased the rainbows. ~ Alex Haley.

(Chasing Rainbows … Memories of a Southern Boyhood is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was published in the March 1980 issue of Panorama TV Magazine. © 1980 Triangle Communications. Inc. All Rights Reserved.)