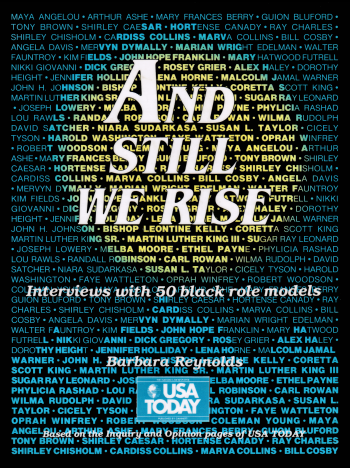

(Barbara Reynolds, Based on the Inquiry And Opinion Pages of USA Today)

And Still We Rise: Interviews With 50 Black Role ModelsAnd Still We Rise By Barbara Reynolds (1988)

Barbara Reynolds, a 20-year veteran of journalism, has been the USA TODAY Inquiry page editor since 1983. This book—the second she has authored—reflects 50 conversations with successful black men and women who can be role models for everyone.

“The role models in this book have most often begun life further back and have expended twice as much energy to go half as far,” says Reynolds. “With much pride, I introduce this book . . . as a celebration of success and accomplishment in the USA.”

In 1975, Reynolds wrote Jesse Jackson: The Man, The Movement, The Myth, which was later retitled Jesse Jackson: America’s David.

And Still We Rise was born of the work of many at USA TODAY and its parent, the Gannett Co. Inc. All 50 personalities in And Still We Rise were interviewed for the Inquiry or Opinion pages of USA TODAY. The interviews have been updated for this book.

“In 1976 Alex Haley and I sat together, jointly feted during an authors’ party. As I forked fresh salmon on china plates, I told Haley about the days in the 1950s when I accompanied my mother, Mae Stewart, to Bexley—a rich suburb of Columbus, Ohio.

She worked in Bexley as a maid earning $8 a day plus car fare. The unwritten law banned blacks from living in the area. It was in that area that we were now being toasted. Together we marveled at the leaps our lives had taken. And Haley told me about his upcoming book, Roots. Years later at his Tennessee country estate, we again shared stories.” – Barbara Reynolds.

Alex Haley Interviewed By Barbara Reynolds

His fame and fortune were made with the saga of his family portrayed for the world in Roots. He began his writing career while in the Coast Guard and free-lanced articles for national publications before his tale of a black family was published. He enjoys writing and researching stories about people, and plans to complete a biography of Madam C.J. Walker, a black woman who became the center of one of the nation’s largest black businesses. He also plans to complete a book on the life of the people of Appalachia. An interview with Haley appeared on the USA TODAY Inquiry page June 27, 1984.

USA Today: Roots made a lot of people cry. Did you cry while writing it?

Haley: Yes. As my writing and research led me to the point where Kunta Kinte is going to be captured I became so immersed in my writing that I talked to him. We would walk around together. And I’ll tell you the truth. I cried like a baby.

USA Today: What was going on?

Haley: I just couldn’t let him get captured. This was my Kunta. This was like my little brother. So I had Kunta take his little brother for a walk. And that walk shouldn’t be in the book. It makes that section too long. But I did it just to hold back from letting Kunta get captured. I remember writing and all of a sudden everything went blank. That’s a convenient thing when you are so distressed that you can’t deal with it anymore. So you let everything go blank.

USA Today: What did you do then?

Haley: I just couldn’t seem to write the capture and let him get into the slave ship and cross the ocean. Then I knew I had to get myself both physically and emotionally closer to what Kunta experienced. So I went to Monrovia, Liberia. After awhile I got word there was a cargo ship going out. It had the perfect name—The African Star.

USA Today: What happened aboard ship?

Haley: Every evening after our dinner I would slip down in the hole. It would be early dark. I would take off my clothing down to my underwear and lie on my back on a plank and fantasize that I was Kunta. By the third night I had a terrible cold. I was feeling miserable. It seemed what I was doing was so foolish. Here I was trying to simulate Kunta in a wooden, stinking, filthy slave ship hole and I am on a big, stately steel ship. That third night I felt so badly about my ridiculousness I could not make myself go down in that hole. Instead, after dinner, I followed the rail of the ship.

USA Today: What were you thinking?

Haley: I stood there looking out into the water in the fog. It seemed like all the troubles in the world came down on me. I owed everybody I could think of. I had borrowed to make this trip. Everybody I knew that knew anything about the book was telling me I was silly. They said it would never amount to anything. I had talked to a number of black scholars. Almost every one of them asked me why in the world would I want to dig up slavery again. “Write about civil rights. Write about anything else.” It seemed almost everybody I knew was against the book. I was tired, beaten down. I didn’t think much of myself. It looked like I was just hanging on to something worthless. And in that spirit a thought appeared in my head: “There is a way to get out of all of this mess right now. No problem.”

USA Today: Jumping overboard?

Haley: Yes. It came to me all I had to do was step through that rail and drop into the sea. I want to stress that there was no sense of fear, no great sense of drama. It was just a feeling that jumping would take care of it. And it was right at that point—standing there on the fantail of that ship—that I had the most uncanny experience.

USA Today: What happened?

Haley: I began to hear conversation behind me. They were saying things like: “No, you must go ahead. You must do it. No, it’s all right. You must continue.” There were my grandmother and Miss Kizzy, who I never dreamed I’d see or hear. There was Chicken George. And they were all speaking to me. I remember when it broke through to me what I was hearing. It was like a tug of war all of a sudden.

USA Today: Did the urge to jump go away?

Haley: No, the urge was too great. The sea was right down there. All I had to do was step out and boom, I’m in it. I had never had an experience like that before. I remember pulling my hands away from that rail as if they were numb. I remember turning quickly and getting on my hands and knees, and scuttering like a crab across the hatch. I wanted to stay in the center of the ship. I didn’t want to get near the rails on either side because the temptation was so great. I cried dry. It was almost like a purging. I cried until there were no more tears.

USA Today: How did you recover?

Haley: I went back down in the hole about midnight and took off my clothes. I laid on my back on the plank and for the first time I was kind of calm. I had a long yellow tablet and a pencil. And I would just lie there on my back. I tried to picture Kunta lying there and what he would be going through. I wrote in the dark. I had my yellow pad with a lot of large scrawling on it. That’s how I started to write that chapter.

USA Today: How did Africa receive Roots?

Haley: I heard in South Africa that Roots was shown through the U.S. Consulate. It wasn’t just standing room for the showing; it was people standing on each other’s heads to see it. I also was asked to give permission for the first half of Roots to be printed in a volume of children’s simplified French for the teacher’s association of West Africa, which extends from the Ivory Coast to Senegal. They were not interested in the U.S. side of Roots, just the African side. They said the translation would provide African students with a better sense of their heritage and culture than any of the books they were studying. That was very moving.

USA Today: What advice do you have for young writers?

Haley: I tell younger writers that indeed it is devastating to be rejected. You feel like the bottom dropped out of your world. But, there is something that I’ve come to know now that the top editors in the top publications come to my farm and enjoy weekends. Every publisher is looking just as desperately for that next exciting new writer. Editors and publishers are making it on the strength of the writers they develop.

USA Today: Did racism handicap you?

Haley: The first stories I sold had nothing to do with blackness. I wrote about sea rescues, animals. Because I was in the service, I couldn’t be out interviewing about racial matters. I had to deal with what I could do on the ship, then get ashore and rush to a library.

USA Today: What should others, particularly blacks, do to make more progress as writers?

Haley: We’ve got to be less accepting of “second-rateness.” At least 60 percent of our problems are our own problems. Problems that we can solve. I know that 15 sociologists or other kinds of people would jump to attack my saying so. But I just never accepted that I couldn’t do and couldn’t be. Maybe it has a lot to do with my being a writer. People had told me they wouldn’t hire me but I soon figured out that writing was something I could do myself.

USA Today: You wrote Roots and now you are writing a book about Madam C.J. Walker, one of the nation’s earliest black business owners, aboard a ship. Why do you do your writing on ships?

Haley: A cargo ship carries freight and a maximum of 12 passengers. And they are very quiet and lonely and low-keyed. Most of the people who go are people who want to eat or play cards or be calm. The ship goes to the most glamorous places on earth. And they unload their cargo and take on more and go on to the next. There is no whipped cream and orchestra and dancing. For me it is exquisite isolation. No phone, no this, that and the other. If you have to contact somebody, you could do it by telex. It’s fantastic. I average literally 14 to 16 hours of work every day.

USA Today: You are also writing a book about Appalachia. How did that come about?

Haley: The general image of the people there is the cartoon, Snuffy Smith. That is not a true picture. These are culturally rich, marvelous people. They live with what they can do with their hands. They distrust that which is store bought. Deals are made to this day with a handshake. And I was very attracted to that. They are holding on more than most of us do to yesteryear. Mostly white, they are really marvelous people.

USA Today: You have a home on 128 acres in Norris, Tenn., a stone mansion and two condominiums in Knoxville and other property. How much did you make on Roots and its spinoffs?

Haley: I really have no idea. The best answer I have is millions. I don’t know. I don’t have all that many millions now. And then next year I might have more or I might have less. I’m really not so carried away with money as a lot of others are. I take the view that if I have enough to do what I want to do, I am not really awfully concerned about building up the number of millions.

(The above interview is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. And Still We Rise: Interviews With 50 Black Role Models Is Based on the Inquiry And Opinion Pages of USA Today. © 2009 Gannett New Media Services, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)