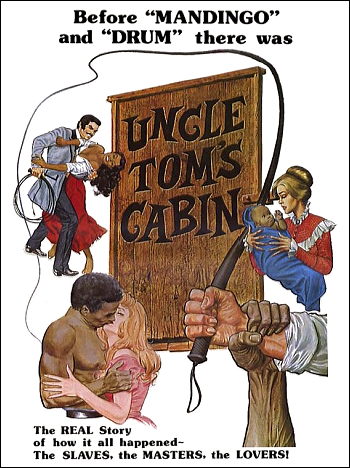

(In ‘Uncle Tom’ Are Our Guilt And Hope by Alex Haley was originally published on March 1, 1964 in The New York Times.)

On March 1, 1964, this article by Alex Haley appeared in The New York Times as a result of Muhammad Ali calling Joe Frazier an “Uncle Tom” just before their first fight.

In this article, Haley analyzes the term “Uncle Tom” from its inception in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to its usage in the 1960s. He defines its meaning during his present context as “A Negro accused by another of comporting himself among white people in a manner which the accuser interprets as servile or cowardly; or a Negro who other Negros feel has betrayed, or sullied, in any way, a dignified, militant, forthright Negro image.”

“Tomming,” Haley writes, “represented a practical means of coexisting with the dominant whites” in the early twentieth century, but it was now looked down upon by the black population. Haley brings up several recent libel suits that black leaders had brought against others for naming them as “Uncle Toms” in order to demonstrate this point.

“Uncle Tom” had been applied to Booker T. Washington by W. E. B. DuBois, and then to DuBois by Marcus Garvey, which shows the growing radicalization of the black protest movement in the early twentieth century and the reemergence of Turner’s vision, which attacked the root of the oppressive nature of the American political economy.

In Haley’s contemporary context, “Uncle Tom” was applied to all who took a gradual approach to the problem of structural victimization. “Uncle-Tomming” was especially prominent in the ghettos of America’s large cities, demonstrating a resistance to transplanting the civil rights ideology developed in the South to the urban poor in the North.

In akron, Ohio, recently a local Negro political and civic leader, Mrs. Bertha B. Moore, brought suit for libel against a Negro weekly newspaper, The Cleveland Call and Post, for printing a “false report” that she had been called an “Uncle Tom.” In Chester, Pa., a Negro clergyman, the Rev. Donald G. Ming, is pressing libel charges against the leader of a local school-integration drive for having called him an “Uncle Tom.” Mrs. Moore won her suit—and $32,000 in damages—with an all-white jury. As of this writing, the Rev. Mr. Ming’s case is pending.

What specifically does the term mean, to produce among Negroes such emotional reactions?

In Mrs. Moore’s courtroom testimony, it meant: “A Negro who sells out other Negroes for money, public recognition or political preference.” The defendant newspaper objected that “Uncle Tom” implied no disloyalty to associates, but merely indicated “one with whom you disagree.”

A more all-embracing definition than either offered is: “A Negro accused by another of comporting himself among white people in a manner which the accuser interprets as servile or cowardly: or a Negro who other Negroes feel has betrayed, or sullied, in any way, a dignified, militant, forthright Negro image.” “Tomming” is the verb form. About the only synonym is “handkerchief head,” much less frequently used.

Mrs. Moore, explaining for the white jurors some background, said, “ ’Uncle Tom’ originally was a deeply religious, subservient hero in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel [Uncle Tom’s Cabin]—but the meaning of the words has changed over the years.” More precisely, the attitude of the American Negro toward an “Uncle Tom” image is what has undergone a radical change. To trace this development requires some review.

Mrs. stowe’s hero is a white-haired, pious, loyal slave-foreman. Though warned that he is about to be sold, he feels it against his Christian principles to run away. While being shipped downriver, he leaps overboard and saves from drowning a wealthy man’s small daughter, Little Eva. The grateful father buys Uncle Tom, and in a New Orleans mansion the old slave and the angelic child read the Bible and sing hymns. Then Little Eva develops tuberculosis. Dying, she extracts her father’s promise to free Uncle Tom.

But, too soon, the grieving father is killed in a brawl. His widow sells all her slaves to the cruel, Yankee-born slave dealer, Simon Legree. Ordered by Legree to flog another slave, Uncle Tom refuses, on Christian grounds, and himself is flogged. Then Legree threatens to beat him to death unless he tells where some escaped slaves are hiding. Uncle Tom, who does not know the hiding place, begs Legree to avoid damning himself through needless cruelty. Legree has the fatal beating administered, as Uncle Tom prays to God to forgive Legree.

Uncle Tom, dying, sees his original good master’s son arrive to buy his freedom. The young master berates Legree, knocks him down and swears, “From this hour, I will do what one man can to drive this curse of slavery from our land.”

The novel, published in March, 1852, leaped to a global renown. Abraham Lincoln is said to have remarked wryly to Mrs. Stow that she started the Civil War. The novel’s indisputable historical role has impelled scholarly controversy about who was the real model for Mrs. Stowe’s hero, cast as a Christian slave, the highest characterization of a black chattel that the era would allow.

The majority candidate is Josiah Benson, a Kentucky slave. It is known that Henson in person told Mrs. Stowe his graphic story before she set out to arouse white Christian consciences against slavery. But there scarcely could have been a greater difference in the personalities, perspectives and actions of the fictional hero and the real-life hero.

A pious slave-foreman like Uncle Tom, Henson personally fared relatively well, by the standards of the system. But it proved more than he could stand and he decided to escape via the Underground Railroad to Canada. His intelligence and militancy quickly made him a leader there among other slave fugitives. He commenced a succession of daring returns into the South until he ranked as one of the Underground Railroad’s most able “conductors,” having helped 118 more slaves escape to freedom.

Turning next to speaking in abolitionist New England, Henson raised enough funds to establish a school for escaped slaves in Dawn, Canada. Touring Europe, finally, he was the first fugitive black hero to be introduced to Queen Victoria.

Mrs. Stowe prophetically feared that dramatization of her book by the then “sinful” theater very likely would vulgarize her work’s intended Christian purpose. In 1852, theatrical producers could adapt any published fiction without the author’s permission. And that year did see the beginning of a spate of terrible caricatured “Uncle Tom” shows on their way to becoming, in theatrical terms, as phenomenally successful as the book.

These productions retained only the most sob-soaked scenes, mortared together with “nigger minstrel” dances and lyrics. Little Eva ascending heavenward on a white dove was counterposed against a monkeylike, unbelievably stupid pickaninny, Topsy. Though Mrs. Stowe wrote of no dogs, the theater invented the classic chase of Eliza crossing the ice. British companies added a scene in which Simon Legree with dogs closed in on a runaway slave, with horrible off-stage noises as the pack mangled their quarry. And always in the major role, of course, was a grinning, bowing, praying, forever-forgiving, wooly-headed “Uncle Tom.”

For generations, hundreds of “Tom” companies played and replayed every American city and hamlet outside the South. Translations by the dozens thrived no less in the homelands of countless future American immigrants. When finally, in the nineteen-twenties, automobiles and movies killed history’s most successful theatrical venture, some 70 years of repetition had infected the Western world with an incalculably poisonous “Topsy” and “Uncle Tom” image of the American Negro.

In this century’s early decades, when most Negroes lived in the South, “Tomming” represented a practical means of coexisting with the dominant whites, in communities where a Negro even suspected of being at odds with Southern customs was in big trouble. Millions of Southern-reared Negroes, including migrants to the North, simply and pragmatically adopted the grinning, feet-scuffing, head-scratching, “Yassuh-boss” masquerade. They found that both Southern and Northern whites, amused and psychologically disarmed, automatically were more cooperative in granting or supplying the Negroes’ usually meager wants.

Not only the uneducated Negroes, among themselves, chuckled at “fooling white folks.” In Southern Negro schools, including colleges, no principal or president long existed without some adroitness in “Tomming,” however finessed. How thoroughly philanthropy and “Tomming” became married—and remained so—is illustrated in a recent incident related by Louis Lomax in his book The Negro Revolt. Lomax tells how a Negro college president delivered a careful presentation for vital funds before an audience of white patrons. At the end, one woman rose and asked if he would sing the old Negro spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The astounded college president, collecting himself, sang—and went home with his needed $50,000.

It is unfortunate that more of both Southern and Northern whites, or at least their leaders, did not perceive the danger of the white illusion that Negroes were “satisfied” with living peripherally in a “second-class” status. The result today is the emotional revolt of the Negro masses advancing rapidly—sometimes even irrationally—against whatever is interpreted to smack of the old “Uncle Tom” image. It is in this climate and mood that Negroes have made the words “Uncle Tom” a traitor like indictment. White people, quoting what some Negro has said to them in private, can cause other Negroes to indict him as an “Uncle Tom”—for having, say, tended to support a “go-slow” attitude. But actually to document an “Uncle Tom” is impossible. He exists only in his accuser’s subjective opinion.

There has been scarcely a single Negro leader whom the “Uncle Tom” charge has not stung. The most generally recognized Negro leader ever in America was Dr. Booker T. Washington. At the same time that he enjoyed the respect, if not the admiration of most whites, and the reverence of most Negroes, Dr. Washington was being bitterly attacked as an “accommodating Uncle Tom” by a powerful, militant intellectual camp of Negroes led by the late Dr. W. E. B. DuBois.

And hurled in turn at Dr. DuBois and his camp, in the nineteen-twenties, was the denunciation: “Uncle Toms . . . weak-kneed, cringing sycophants to the white man,” by the fiery Black Nationalist leader, Marcus Aurelius Garvey, whose huge “Back to Africa” movement lured millions of Negroes.

The counterpart to Garvey’s movement now would be the Black Muslims. That organization’s chief spokesman until recently, Malcolm X, has “Uncle Tommed” practically every Negro leader in the nation. He sometimes pins the label upon whole categories. Negro ministers he has assailed as “the Rev. Uncle Toms . . . parroting the white man’s religion.” His “Dr. Uncle Thomases, Ph.D.” he applies, at large, to Negro intellectuals. In “those black bodies with white heads” he implies that the Negroes of the N.A.A.C.P., the Urban League and similar agencies are “Uncle Toms” for permitting white chairmen or presidents to be their “brains.”

And if one listens to some of the street-corner incendiaries who are haranguing crowds in such ghettos as Harlem and South Side Chicago today, it should not be at all surprising to hear “Uncle Toms!” flung at even the Black Muslims.

The tensions that are building in the ghettos of America’s large cities signal an increasing mass of truculent Negroes, among whom are many quick to fling “Uncle Tom” at any suspicion of lagging militancy by even the most dedicated Negro leaders. The charge, if it sticks, is so professionally fatal that a significant joke, popular among Negroes, depicts an ousted leader running alongside a marching line, pleading: “How’m I going to lead if you don’t tell me where you’re going?”

The fact is that the Olympian Negro leader regarded by most of his race with awe, such as Dr. Washington or the late Walter White of the N.A.A.C.P., now is gone forever. Today, a Negro leader can only quarterback, doing well if he contains the kibitzers and the insurgents.

Privately, not a few Negro leaders do wish that there was somewhat less demand for a regular fare of headline-making, “dramatic” statements and actions. These consume time that might be more effectively spent in quiet, tough, statesmanlike bargaining, behind the scenes, with local and national white power structures.

“There are a hundred American corporations, and their leaders, whose weight on our side could end this whole thing; what we Negroes need to do is quit getting madder and get smart,” I was told by a Negro whose sensitive national position underlies his request for anonymity. “We need to evolve now from demonstrations into negotiations,” he said. He cited the example of American labor. When it had demonstrated its bloc power for militant action, its leaders sat down with management and, relatively soon, revolutionized labor’s position in this country.

Mrs. stowe’s novel, for all its faults, is redeemed by the fact that it helped to end the institution of slavery. It is a deep irony that, a century later, the very name of Mrs. Stowe’s hero is the worst insult the slaves’ descendants can hurl at one another out of their frustrations in seeking what all other Americans take for granted.

Both the guilt and the hope of America, then, are inherent in “Uncle Tom”—the guilt of slavery and the hope that the day will come when white men, honestly, will fling the epithet “Uncle Tom” at the Negro who does not stand up as a man among men. ~ Alex Haley.

(In ‘Uncle Tom’ Are Our Guilt And Hope is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the March 1, 1964 issue of The New York Times. © 1964 The New York Times Company. All Rights Reserved.)