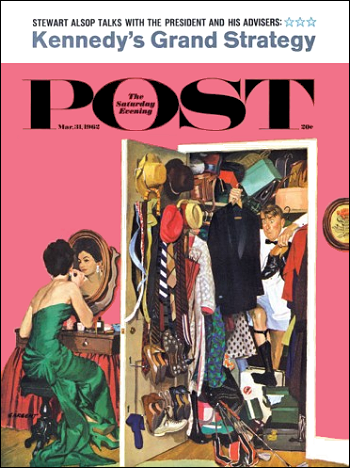

(Phyllis Diller: The Unlikeliest Star was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on March 31, 1962.)

(Phyllis Diller: The Unlikeliest Star was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on March 31, 1962.)

140 Columbus Avenue. Once home to the performance venue known as the Purple Onion, this place has seen many famous headliners, often before they were famous. Phyllis Diller, who’s now so big that she’s famous for something as simple as her laugh, was still struggling when she played a 2-week engagement here in the late 1950s.

Alex Haley tried to interview her during that engagement, and she told him, “No, not yet, baby. I’m not big enough for you to be able to sell it, and you’re not big enough to get it sold in the right place.”

Six years later, while working as a reporter for the Saturday Evening Post, Haley saw that Diller was playing at the hungry i (a club formally located at 599 Jackson Street), so he went in and knocked on her dressing-room door. She jumped out of her chair and hugged him, saying, “Baby, we’ve made it.” (She also was one of the first people to contact Haley after his success with Roots.)

Among many other performers, one who stood out and sang here during the 1950s, was Maya Angelou, author of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and the poet who read at the inauguration of President Clinton. Angelou later portrayed Nyo Boto, the Grandmother, in Alex Haley’s triumphant (made for television novel), Roots.

Comedy legend Phyllis Diller has been in showbiz a long time, but her act and persona were just slightly different in her early days of stand-up. In the magazine article below, Diller spoke about how her material changed, and how she came to performing comedy relatively late in the game.

Phyllis Diller: The Unlikeliest Star

In San Francisco’s busy cellar night spot, the hungry i, the dressing-room buzzer signaled stage time for the nation’s top nightclub comedienne, Phyllis Diller. Thin, freckled and forty-four, Phyllis answered the buzzer with a vibrant Bronx cheer and gave her hair, peroxided a glaring white, a few last licks with a brush. She pushed a pastel pink cigarette into a long, fake-jeweled holder and then flipped a ratty fur piece over her forearm. Briefly she held still, grimacing and cawing as if she were being garroted, while her husband Sherwood clasped a glittering, bib-sized rhinestone choker around her neck. In the dressing-table mirror, above the photograph of her five children, she looked like someone’s raffish grandmother caricaturing Cinderella.

Phyllis reached the stage with a rubbery lurch, and the packed audience burst into laughter. “A woman hits forty,” she drawled, “going ninety miles an hour. It’s very embarrassing—you and your mother approaching the same age from opposite directions.” She staggered slightly and curled an arm over her head. “You’re looking at a Slenderella reject!” she announced. “Honey, I went from baby fat to middle-age spread so fast I didn’t have a good five minutes. If I had, I would have given a party.”

For the next twenty-five minutes Phyllis had the women in the audience shrieking, The zany comedienne was their gal, satirizing in herself their own familiar frustrations and harassments as women and housewives.

“Everything I tell you about me has happened, honey,” she declared, dangling high her tacky fur piece. “My stole! Isn’t that pitiful? How unsuccessful can a girl look? People think I’m wearing anchovies! The worst of it is, I trapped these under my own sink!”

The women howled as Phyllis lit into the loutish, make-believe husband she calls “Old Fangface.” “This creature—everything that goes wrong is his fault! Last night he put the car in the garage backwards! That shot the hell out of my map. This morning I drove out of the wrong end, going the wrong way on a one-way street. When I finally got home, you should have seen Fangface! He wanted to know how I had driven into the kitchen. I’d made a left turn from the dining room, of course!”

With her audience warmed up, Phyllis proceeded to murder the notion that women are made of sugar and spice. Smacking her overflow midriff, she cracked: “Middle-age fallout, kid! It’s a human blouse.” A beauty-shop receptionist had told her: “Lady, we do repairs, not reclamations!” “That ugly, insulting broad!” snarled Phyllis. “She’s had so many face-liftings there’s nothing left in her shoes.”

Eleven years ago Phyllis Diller was a housewife, penniless and demoralized. Today audiences pack nightclubs to hear her, and millions have seen her on television—on the Jack Paar Show alone over thirty times. Her strongest appeal is to women, but men appreciate her too. Her cult of admirers is swelling steadily. They throng her shows, buy thousands of her LP record album, Phyllis Diller Laughs, and send her fan mail. She now earns as much as $5,000 weekly.

Phyllis plunged into show business in 1955, a thirty-seven-year-old Alameda, California mother of five with no professional experience. She swept to success as a comedienne because early in her career she had the perception to satirize her own domestic experiences as a woman facing middle age, and struck a theme which many modern American women respond to in an extraordinary way. “When I open my mouth, they know I’m one of them,” Phyllis says, “and from that second we both can feel that two-way radar going between us. We girls are compatriots with ten thousand things in common. I’m just the one onstage talking for us.”

Phyllis’s yen to entertain began as a girl in Lima, Ohio, where she grew up the only child of an insurance sales manager and his wife. As an adolescent coloratura, she won praise for school and church concerts, balancing any frustrations she had because she was not, as she puts it, “the type that boys had to lash themselves to masts to stay away from.” After high school Phyllis attended both Northwestern University and an advanced school of music in Chicago. Secretly she practiced a popular repertoire, hoping to sing for nightclubs. But impresarios never let the plain looking co-ed even finish asking to audition. Disgusted with singing, Phyllis returned home, intending to go to a business school; but her parents insisted that she get a music-teaching degree at Bluffton College in Bluffton, Ohio.

Late in Phyllis’s senior year, a fellow student who lived in Bluffton introduced her to his brother, Sherwood Diller. “I took just one look at Sherry and started planning a large family,” Phyllis says frankly. In November, 1939, they eloped, then settled in Bluffton. Phyllis returned to her studies for two more months in order to get her degree.

A son Peter was born three months before Pearl Harbor. The Dillers moved to Alameda, California, and Sherwood became an inspector at the Alameda Naval Air Station. In their small apartment in a jerry-built housing project, Phyllis embarked upon a decade of “working as hard as I think it is possible for a woman to work. I scrubbed, washed, ironed, mended, cooked and had babies. There was never enough money.”

When Phyllis’s father died, her mother came to Alameda and invested her modest inheritance in a big, old house. The first floor was turned over to the Dillers, the second floor to four retired boarders, and two third-floor rooms to Phyllis’s mother. The Dillers’ financial pressures were eased, but Phyllis’s burdens were quadrupled by the added task of playing cleaning woman and nursemaid to the aged, crotchety tenants. “They wanted the kids kept quiet. I’d be scrubbing their halls and toilets and have to dash downstairs to answer our phone for their calls.”

When, in March, 1949, Phyllis’s mother died, Phyllis inherited the big house and the family’s place back in Ohio. A local real-estate woman suggested selling both properties to buy a small house plus a second for rental income. Phyllis and Sherwood trustingly let the agent trick them into signing away everything they owned. In the ensuing mess, the woman was imprisoned and the Dillers moved into a house with a small down payment and a heavy mortgage.

“It was a nightmare,” Phyllis recalls. “Sherwood took a second job as a night watchman and a third job, driving a taxi on weekends.” Soon, though, exhaustion caught up with Sherwood. He was found asleep on his night watchman’s job and lost it. The mortgage company dunned them for late payments, the grocer finally refused credit, and the utilities companies threatened. “I just hurt worrying about getting enough food and clothes for our five kids,” says Phyllis. “But there was something worse. Sherry and I fought constantly. We were giving the kids a negative start in life. I even thought of divorce.”

Incongruously, during this bleak time Phyllis created the style of comedy that makes her so successful today. “To hide our awful mess from the neighborhood, I acted as if I didn’t have a care. I think I began being funny almost unconsciously.” In the corner Laundromat Phyllis began cracking jokes and satirizing the housewife’s life for the women waiting for their clothes to wash. They found Phyllis so hilarious that, encouraged, she would burst into the Laundromat with roses taped to her ears, yards of frothy tulle around her neck and battered cooking utensils as props for spontaneous takeoffs on her sad lot.

The tension inside Phyllis exploded early one Sunday evening. Neither she nor Sherwood can remember what trivial incident made her scream at him, slam out of the house and walk, she thinks, for miles. Passing a strange church, she turned back. “Something forced me,” she says. As she slid down in the last pew she heard the minister reading: “Whatsoever things are true . . . whatsoever things are pure . . . think on these things.”

“The words seemed to be addressed directly to me, as if God Himself were giving me a message,” Phyllis says. To the dismay of her Laundromat audiences, she did not entertain for the next several weeks. “I stayed home,” she says, “having skull-and-soul sessions with myself and reading self-help books. Before, I had always scoffed at claims that anyone could change his life for the better by positive thinking. But considering the shape we were in, I was willing to try anything.

“I didn’t change my life overnight, but at least I glimpsed what I had to do. I had to stop wallowing in negative thoughts about what a hard time we were having. I knew I had to think and work in positive ways with the good things I had—my healthy, obedient children and my hardworking husband. As a start, since we so desperately needed money, I had to go out and get a job.”

Phyllis hired a friendly Negro woman who loved children. “Mabel Bess took right over while I got dressed to see the editor of the San Leandro News-Observer.” Phyllis convinced him that the paper needed a shopping column and that she could write it. Soon Phyllis won a better-paying job writing advertising for a department store. Later she became a continuity writer for Oakland radio station KROW, then went on to station KSFO in San Francisco as head of merchandising and press relations.

During the workday Phyllis entertained her coworkers with the old Laundromat routines and new ones she had developed, “It was fun for me now that I wasn’t hiding something, I was really just being myself.”

Phyllis clowned often for her family as well. “When I quit nagging at life, our home burst with real living.” Time and again, after a spontaneous performance, Sherwood would say, “You ought to turn pro, Phyllis.”

Phyllis insisted that a chasm lay between her homemade acts and professional comedy. “But Sherwood was kindling my old dreams far more than he ever suspected. I kept thinking how positive thinking had helped me succeed in jobs I’d never have dared try previously, and I began asking myself why it couldn’t work in show business.” One lunch hour, while window-shopping, she astonished herself by making a down payment on a silver-sequined sheath. “It just struck me as the kind of dress I’d wear in show business.”

Phyllis argued with herself for weeks before making up her mind. Then one evening she said, “Sherry, I’ve been thinking—we’ve got to talk.” After sixteen years of marriage, he knew her pattern. “You’re ready,” Sherwood said.

A drama coach helped Phyllis develop skits. He concentrated on her own natural delivery and style. Each night she locked herself in her room with a full-length mirror and a tape recorder. After nearly a year Phyllis gave KSFO her notice. She requested an audition at The Purple Onion, a small, popular San Francisco basement club noted for hearing new talent. Luckily her audition came just before the club’s comedian went to New York for a TV show. She was hired as a substitute.

The evening of March 7, 1955, fighting fright with prayers for strength, Phyllis walked out under her first nightclub spotlight. Slithering around a piano, she spoofed Eartha Kitt’s song Monotonous with her own version, called Ridiculous. She lampooned soprano Yma Sumac, clowned with a zither and cracked topical jokes based on newspaper items. The Purple Onion audiences applauded politely, but offstage, in the sour glances of bartenders and waiters, Phyllis saw the real verdict, which she knew she deserved. “I’m just not good enough, Sherry,” she said. “I’ve got a thousand things to learn.”

But she had only two weeks in which to learn them—until the regular comedian returned. Each night she tested new bits of patter, new gestures and preposterous rubbery expressions, to see which made audiences laugh most. When the regular comedian came back, the Purple Onion’s manager, Barry Drew, said, “Phyllis, you’ve got something. We’re going to recall you soon.”

Appreciative audiences soon moved Phyllis to top billing. The Purple Onion loved her, and newspapers, calling her “San Francisco’s own Phyllis Diller,” began to quote her cracks. “You know what keeps me humble? Mirrors! I considered changing my name when I entered show business—but with a face like this, who cares?”

During this time, I dropped by the Onion and met Phyllis between shows. It was astonishing to hear the outlandish funny woman credit “positive thinking” and her family’s cooperation for making her a comedienne. I asked what she predicted for herself, and she looked at me levelly. “In five years, I’ll headline for the i.”

The hungry i was named for the original “hungry intellectual” clientele from which colorful Enrico Banducci built his famous cellar club. Only a block from the Purple Onion, it was miles away in terms of its comic headliners, such as Mort Sahl, Bob Newhart and Jonathan Winters.

But Phyllis erred in her prediction. She played the i less than three years later.

After a record eighty-nine weeks at the Purple Onion, Phyllis signed with a booking agent who seasoned her in small bistros across the United States. She rapidly grew more poised and polished. Dropping the songs and impersonations from her act—”they sagged the pace”—she replaced them with new, slicker versions of her onetime Laundromat humor. Beaming toothy greetings, for example, she would open an imaginary door. “Honey, talk about an upset Fuller Brush man! He didn’t even come back for his car!”

Phyllis’s fervent housewife following had swelled her drawing power; in late 1958 her agent brought her to the Bon Soir in New York. With eye-rolling shrugs, scowls, staggers and a rooster crow laugh, Phyllis worked full time, poking fun at the trials she and her compatriots encountered: “Nowadays, if your kids dynamite the house, they’re insecure! It’s all muzzie’s and dadsie’s fault. Honey, let me tell you about a childhood shakeup. When I was three, my folks sent me out for bubble gum, and while I was out, they moved!”

Nightclubs across the nation were offering Phyllis top fees when in the summer of 1961 she received her bid from the hungry i.

I visited her just after she returned to the West Coast for her hungry i debut, We sat by the pool of the house she had rented near San Francisco, and she looked on happily as her youngsters swam and played. Though every day she had called them long-distance from wherever she was, she had not actually seen them for months.

“They’re fantastic ‘kids,’ ” she once said to me suddenly. “God’s been good. You know, on the road different women will say to me, ‘What a pity you can’t spend more time with your children.’ You know what I tell them? I say that with my kids it hasn’t been how much time, it’s how much love! People who see me clowning never would believe I breast-fed all five of my babies. You can’t find a more old-fashioned modern mother than I am! We worried when I had to have Sherry with me as manager, and the kids went to live with his sister in St. Louis. Those kids helped make my career, and it’s proved just great for them too.”

Phyllis continues to write all her own material, jotting down whatever she sees, hears or thinks her audiences might find “pleasantly hysterical.” In a limousine, whizzing past a roadside sign, No Littering—$50 Fine, she scribbled the words on a card, adding “How much can a poor, pregnant cat make?” On stage Phyllis ad-libs easily. Once when a loose underarm shield slid down inside her sleeve, she blithely extracted it and tossed it on the piano, crowing, “I’m stripping from the inside!” Women in the audience, fully aware how undependable underwear can be, were convulsed.

Phyllis has had her share of failures. “Honey, I’ve been smashed!” After one night, the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami fired her. She flubbed a Hollywood screen test and once, after three rehearsals, the Steve Allen Show dropped her. But Phyllis never once considered giving up, “I’ve had fear thoughts—I’m only human. But every fear thought and I battled it out eyeball to eyeball, and I won.” In Phyllis’s next try at Hollywood, she got the bit part of Texas Guinan in Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass.

To laugh at Phyllis is really to admire the courage of all “we girls” who cope every day with the problems of being a woman and raising a family. During her triumphant San Francisco homecoming, the Purple Onion astonishingly displayed large signs, Phyllis Diller Across Street at hungry i. The Purple Onion’s manager, Barry Drew, shrugged when asked to explain. “It’s just the Onion’s attitude about Phyllis. If you know her, she’s therapeutic.” ~ Alex Haley.

(Phyllis Diller: The Unlikeliest Star by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on March 31, 1962. © 1962 Saturday Evening Post Society. All Rights Reserved.)