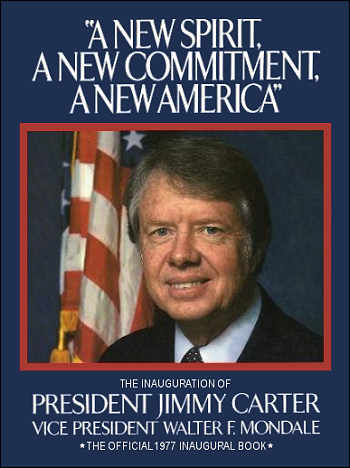

(President Jimmy Carter by Alex Haley was originally published in “A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America”: The Inauguration of President Jimmy Carter and Vice President Walter F. Mondale by the 1977 Inaugural Committee.)

(President Jimmy Carter by Alex Haley was originally published in “A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America”: The Inauguration of President Jimmy Carter and Vice President Walter F. Mondale by the 1977 Inaugural Committee.)

The Oath Of Office: “I, Jimmy Carter, do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States. So help me God.”

“For myself and for our nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land.

“In this outward and physical ceremony we attest once again to the inner and spiritual strength of our nation. As my high school teacher. Miss Julia Coleman, used to say. ‘We must adjust to changing times and still hold to unchanging principles.’ Here before me is a Bible used in the inauguration of our first President in 1789, and I have just taken the oath of office on the Bible my mother gave me just a few years ago, opened to a timeless admonition from the ancient prophet Micah: ‘He hath showed thee. O man, what is good: and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?’

“This inauguration ceremony marks a new beginning, a new dedication within our government and a new spirit among us all. A President may sense and proclaim that new spirit, but only a people can provide it. Two centuries ago our nation’s birth was a milestone in the long quest for freedom. But the bold and brilliant dream which excited the founders of this nation still awaits its consummation. I have no new dream to set forth today, but rather urge a fresh faith in the old dream. Ours was the first society openly to define itself in terms of both spirituality and human liberty. It is that unique self-definition which has given us an exceptional appeal…” ~ Jimmy Carter.

President Jimmy Carter

From Boyhood On A Red-Dirt Farm To The Governorship of Georgia

In February, 1932, the farmers in southwest Georgia were finishing the first plowing. Afterward the land would be harrowed and the broken cotton stalks and clumps of Bermuda grass dragged to the edge of the fields and set afire. Then, the turning plows would create endless fields of reddish earth rows, each row enriched with an inch-width of white, coarsely powdered guano fertilizer. Corn would be planted in early March, then the cotton and the other crops. Around Archery and Plains in Sumter County, the principal crop was peanuts.

Before the first plants even peeped above the earth, seven-year-old Jimmy Carter was taking part in an all-out effort to beat down the rampant Bermuda grass. As soon as Jimmy had turned five his daddy, Earl Carter, put him to toting a bucket of drinking water among the family’s black tenants, who chopped at the grass with long hoes from daylight to dark. Not until early June, when the cornstalks got as tall as mules’ ears, did there come a brief “lay by” time when the workers got about two weeks to rest. Returning to the fields they scythed the ripened grain, then they picked watermelons and hauled them to the Seaboard railroad cars that would take them up North. Then came the first massive cotton picking. Finally, everyone harvested the peanuts, deftly jerking the vines from the earth, with each set of roots holding between thirty and fifty of the plump, light tan nuts, and the vines were stacked so that the nuts could dry in the sun.

Each Saturday morning, now, Jimmy would be out in the nearest field before sunrise. Filling two large buckets with choice peanuts, he would wash them and then boil them in salty water while he rushed through his regular morning; chores: he fed the chickens, gathered the eggs, milked a cow, chopped some stovewood and pumped some water for his mother, Lillian, who by then would be cooking breakfast before leaving for her job as a registered nurse. Packing his peanuts into sacks and then into two large picnic baskets, Jimmy would trudge to Plains with that load, about three miles along the railroad track.

Jimmy sold the boiled peanuts for a nickel a bag, up and down the main street of Plains. The Saturday crowd, averaging three hundred or even four hundred farm people, circulated or chitchatted, or played checkers. The aroma of barbecue and cut watermelons was usually in the air, along with small biting flies that made people slap suddenly at their necks or arms, and made the mules—hitched among the wagons, carts and T-model Fords—snort, stomp, swish their tails and shudder their skins. Jimmy would thank each customer, flashing his toothy grin. He might also treat himself to a triple-dip ice cream cone or two, and store-bought candy, and if he had time he would rip and run with some of his schoolmates who lived in town. Sometimes, he would ride on the three-car Seaboard mail train the ten miles to Americus, Georgia, where he would buy a nickel ticket at the Rylander Theater and see a movie.

Around Plains, where everyone had a mental file about everyone else, Earl and Lillian Carter’s boy already had a reputation for being feisty and industrious. With eyes blazing and fists flying he had gone after a much larger schoolmate whose rough playing had caused Jimmy’s sister Gloria to break her arm. On the other hand, when Gloria hit Jimmy with a wrench, he seized his BB gun and plinked her in the behind. Annoyed one night by the noise of a party his parents were giving, he left his bedroom to sleep in his treehouse, then refused to answer when he was called around midnight, thereby earning himself a memorable switching in the morning.

When Jimmy was nine years old, the Depression was at its lowest point. People around Plains had nothing to eat but what they could grow and catch. Having heard his father swearing that the whole country was going under unless crop prices improved—cotton was then a nickel a pound, peanuts a penny—Jimmy asked permission to invest his savings in five bales of cotton.

Not so many white playmates lived near the Carter farm, so Jimmy played mostly with black boys, some of whose parents were tenants or sharecroppers on Earl Carter’s farm. His favorite playmate was A.D. Davis. As soon as they could convince the black foreman, Uncle Jack Clark, that they had done enough work, Jimmy and A.D. would take off, both barefooted, usually with Jimmy’s bulldog Bozo. They rolled their barrel hoops down the reddish roads, or shucked off their pants and skinny-dipped in various small ponds near the Carter farm. Or they’d sit on old disc plow blades to go sliding down slick hillocks of pinestraw. The kites they made and flew had long tails festooned with squirming June bugs. They made aerial spinners of corncobs and rooster tail feathers; got stung digging honey from bee trees; harvested wild berries, persimmons, plums and sassafras; dammed up small streams with sticks and red clay; stole rides on Earl Carter’s prized bull calf.

One day they went to Americus, where Jimmy insisted they see the movie at the Rylander Theater and that A.D. sit with him downstairs in the white-only section. But as a muttering arose, A.D. slipped upstairs to the “crow’s nest” followed by Jimmy demanding that he come back downstairs. But A.D. wouldn’t and they both left, highly indignant. They found themselves sometimes involved now in embarrassed, confused conversations about race. “Don’t know as I’m ever going to start calling you ‘Mr. Jimmy,’ ” said A.D., and Jimmy replied, “I wouldn’t blame you—I wouldn’t either.”

As he grew older, Jimmy began to spend a lot more of his time in Plains. He teamed up with his cousin Hugh Carter and sold hamburgers and ice cream, as well as old newspapers, scrap iron and penny-winkle grubs, which make good fishing bait. The Depression was lifting now, and when the price of cotton went to eighteen cents a pound, Jimmy sold his five nickel-a-pound bales and bought five tenant shacks. Soon he was collecting $16.50 a month in rents—and evoking much head-wagging in Plains, where people could tell that Jimmy had inherited his father’s business instincts.

About this time Earl Carter opened a new kind of business in Plains. Instead of every farmer hauling peanuts to the oil mill, Carter would pay the best market prices for each man’s harvest and sell to the oil mill in wholesale quantities. Business soon expanded to the credit sales of fertilizer, seeds and other supplies. Young Jimmy saw his father bent over his credit ledgers for hours on end.

Frequently now, Jimmy would go thumbing for the thousandth time through his Naval Academy catalogue. He and his father hoped that he would get an appointment to Annapolis, but he worried about the tough physical and academic entrance examinations. He determined to put on more weight. He studied calculus. After Pearl Harbor, Jimmy spent a year at Georgia Southwestern College, then went on to Georgia Tech in Atlanta before enrolling at the Naval Academy in 1943.

Nothing in the catalogue prepared Jimmy for the hazing that the annual crop of plebes was subjected to. Plebe Carter endured his normal share of hazing until one day he refused an upper-classman’s order to sing “Marching Through Georgia”—and the rest of his first year became a pure hell. Called a Cracker, often denied food, knocked sprawling with huge serving platters, regularly paddled with long-handled serving spoons, he never did sing General Sherman’s song.

That plebe year behind him at last, Midshipman Carter achieved outstanding scholastic averages in gunnery, seamanship, navigation, astronomy, naval tactics and Spanish. He took ballroom dancing, participated in cross-country races and in intercompany football. He learned to fly seaplanes, and of course he learned to be a seaman.

Each summer’s training cruise was followed by a brief vacation, and after his junior year Jimmy went home to Plains. One afternoon with but two remaining days at home, his sister Ruth appeared with her friend, Rosalynn Smith, whom Jimmy had known much of his life without giving much thought to her; she was younger, his sister’s friend.

Yet that evening he invited her to go to a movie with Ruth and her boyfriend, and later that night Jimmy astounded his mother as much as himself by announcing, “Rosalynn’s the girl I want to marry.”

He lay in his room that night reviewing everything that he—and everyone else in Plains—knew about Rosalynn. The oldest of four children, she had been thirteen when leukemia killed her father, the town mechanic; Rosalynn was helping her mother raise the three younger children. The townspeople respected Rosalynn’s strength, stability and self-reliance as well as her thrift and religious devotion. At eighteen she completed a two-year general diploma course at Georgia Southwestern Junior College.

The next night she saw him off as he caught the train to Annapolis. They wrote to each other daily, and they were together when he returned home for Christmas—but she refused his proposal of marriage. Then visiting him at Annapolis two months later, Rosalynn changed her mind. The wedding date was set to follow his graduation in June, 1946.

After the simple ceremony in the packed Plains church, Ensign and Mrs. Carter settled down in a small apartment in Norfolk, Virginia, where he had been assigned to the battleship Wyoming. He was reassigned to the Mississippi. In July, 1947, their son was born, named John William but called “Jack.” Though the navy life was more exciting than anything they had ever known in their tiny, dusty, Georgia hometown, it was frustrating with his ship so often and so long at sea. Hoping to get them more time together somehow, Jimmy applied for a Rhodes scholarship; the request was turned down, but he was accepted for submarine officers’ training in New London, Connecticut.

He finished third among fifty-two classmates, drawing a submarine assignment—U.S.S. Pomfret—that would send the Carters to Oahu, Hawaii, for the next four years. When Jimmy was home, they loved packing a picnic hamper and strolling barefoot on the beach with Jack scampering before them, filling his pail with multi-colored seashells, and suddenly rushing ahead, squealing with delight as his presence sent little armies of walnut-sized sandcrabs fleeing. Caring for Jack alone when Jimmy was away, Rosalynn sewed and sometimes shared coffee chitchat with other submariners’ wives—who later described her as a “shy” and “very private” person—and she read more books than she once would have thought existed. She became pregnant again and a second son, James Earl, was born, whom the hospital nurses nicknamed “Chip.”

The Pomfret was reassigned to San Diego in 1950 and Carter was ordered to New London as senior officer of the pre-commissioning detail of the first new ship built by the navy since the end of World War II, K-1, a small submarine designed to fight submerged enemy vessels. He supervised the K-1’s construction, the installing of special sonar equipment, and developed operating procedures to be used on the ship.

Carter was not senior enough to have a ship of his own while serving on the K-1, though he was qualified to command a submarine. Sometimes, he and the other officers and crew remained submerged for weeks at a time in the small sub, testing the sophisticated underwater listening equipment. Once, a crewman went mad with claustrophobia and had to be strapped to a bunk until the K-1 could surface and he could be taken away by helicopter to a hospital. It was not easy duty. But Carter and his fellow submariners felt a great personal closeness, proud of being part of such a demanding service and of the high standards required. When Carter heard that Admiral Hyman Rickover had persuaded the navy to begin a nuclear submarine program, he applied at once to become part of such a challenging assignment. This returned them to New London, where a third son, Jeffrey, was born soon after they arrived. Carter and three other young officers were sent to Schenectady, New York, to oversee the developing prototype nuclear submarine, Sea Wolf. By day the lieutenant taught his prospective crewmen physics, math and the ABC’s of nuclear reactors. He attended Union College to study atomic science and technology. The fact that he had managed to qualify for this handpicked nuclear submarine post at the age of twenty-eight pointed him on a straight course to an eventual nuclear admiralty.

But then came a phone call from Plains; Earl Carter was dying with inoperable cancer. Jimmy and his family drove 1,100 miles nearly nonstop to return home, and once there he plunged into work at the family warehouse, trying his best to be a substitute for his father. From one customer after another, he heard stories of how in troubled times “just about everybody” had come to Earl Carter, who had lent cash and extended substantial credit when no bank would, later even canceling out some of the debts—demanding only that none of his family be told.

In the early evenings Jimmy sat at his father’s bedside. Since Jimmy had grown up and left home, they had on occasion gotten into harsh arguments on social and political issues. But now his stricken father lay thanking his son for coming, telling him how proudly he had followed Jimmy’s navy career.

When Karl Carter died, Jimmy and his sister Ruth went driving along the red clay roads around Plains, breaking the news to white and black, many of whom burst into tears. At the funeral, mourners filled even the yard of the Plains Baptist Church.

When it was over, Jimmy and Rosalynn returned to Schenectady, and he began to brood. It was a while before he could bring himself to share his anguish even with Rosalynn. His father had been a mainstay, a caretaker of their community, he told her. Who else now could fill his father’s place? Rosalynn understood Jimmy’s feelings, but she also knew that she must not permit her husband to wreck his brilliant career, his years of disciplined studying. And she wondered if they could ever be content to live again in Plains. The worst arguments they’d had before had generally been solved quickly, but this time it was different. His determination to return brought out a similarly fierce determination in Rosalynn, but when she sensed that she might be wrecking their marriage, she gave in.

Back in Plains, they moved into a $30-a-month apartment in the Plains public housing project. Rosalynn would look at him at times wondering to herself what kind of man would jettison a brilliant, secure career to return to tiny, dusty Plains and raise peanuts. Returning late each night, he kept her posted on the family’s financial state of affairs. Earl Carter had left some cash, most of which went to taxes, and some land, and the accounts receivable—the total of outright cash loans and supplies he had issued on credit to scores of local farmers. One worry was how many of the creditors might simply abandon the dead man’s debts. But even those who planned to pay the Carters back couldn’t do so without a reasonable harvest, and the outlook was for a drought.

Rosalynn began going to the warehouse, studying the books closely. Soon she plunged in more deeply and worked her way through a good course in professional accounting. Though the family was existing on savings bonds, Jimmy had the habit of arriving for lunch with some uninvited guest. So they shared Rosalynn’s homemade chicken soup, stews, and casseroles with a succession of county agents and farmers whose brains her husband was eagerly and candidly picking. He had to get reoriented, he told Rosalynn, and learn about the revolutionary new agriculture techniques, machines and chemicals that had turned farming into a science: hardly a hand-plow or working mule could now be found in Sumter County.

The 1954 drought was far worse than had been expected. Weekday after weekday only a trickle of wagons arrived at the warehouse, loaded with generally runty peanuts. With the nearly record poor harvest, few warehouse debts got paid. Over and over again in the small office, Rosalynn heard her husband telling their customers. “Of course, I understand.” Her final accounting showed their year’s net profit to be $254.

One day in the early spring of 1955, the Plains police chief dropped by the warehouse accompanied by a Baptist preacher who also served as the railroad depot agent. They were forming a local chapter of the White Citizens Council, and they asked him to join. Jimmy refused. They left abruptly wearing set, flushed faces. Before long the two men returned accompanied by some of the warehouse’s few cash customers, one of whom explained to Jimmy that he was risking his personal reputation and his family’s business if he still refused to join. Jimmy told them that he had no intention of joining: if necessary, he decided, he and his family would leave Plains. Overnight, most of their customers vanished. Worst of all, some people in the congregation whom they had known all their lives stopped speaking to them. Gradually, though, the customers began to return. It had gone around the grapevine that Jimmy’s naval career had warped him, but that now he’d come around.

He didn’t. After efforts to integrate a white Baptist church in Americus created a furor there, the Plains Baptist Church proposed to bar all blacks or civil rights workers; only Jimmy, Rosalynn and Lillian Carter, and Jeffrey and Chip Carter and one other member of the entire congregation voted no, against fifty yea’s. Again many quit speaking to the dissident Carters. Even so, the people of Plains had deep respect for honest dealing and hard work, and it was commonly agreed that there wasn’t a smarter young couple in town than Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter.

Rosalynn was painfully shy, but she had the trust of the farmers when “settling up” time came. Jimmy boasted to customers that in addition to being his wife, Rosalynn had become his indispensable business partner. By the late fifties, they had installed more than $100,000 worth of peanut-hulling machinery. And in 1960, Rosalynn showed Jimmy her careful figures that indicated they really could afford to build the house they wanted; the next year the five of them moved into their new ranch-style house of Georgia clay red bricks.

One day in 1962, Jimmy told Rosalynn that the Georgia legislature was being reapportioned and that he still had time to file for the state senate. His campaign was most notable for its feverishness, but when election day finally came he got the shock of his life. At one polling place in Quitman County, voters were marking their ballots in full view of the local political boss, who was telling them to vote for Carter’s opponent. The man was even taking the ballots out of the pasteboard box and examining them.

Thus Carter began to learn an infuriating lesson about the capacities of corrupt politicians to cover up their crookedness. Eventually, reporter John Pennington of the Atlanta Journal published an expose of Quitman County politics that led to a formal court action. The prosecution showed that the county voting register included the names of the departed, the dead, and the imprisoned. The court ordered a new election and Jimmy Carter won by 1500 votes.

Senator Carter served two terms that spanned a period when race had become the most incendiary topic in Southern politics. Jimmy had a few colleagues who were not content to accept the bitter irrationalities they heard from older legislators. The young senators agreed that the traditional social order could hardly be changed overnight, but that there were a few decent things they could do to begin changing it. Jimmy himself had come to believe that racial, ethnic and religious prejudice was the most costly flaw in the U.S. fabric—probably the greatest obstacle to our ever realizing our fullest national potential.

Accordingly, Jimmy took a strong stand against Georgia’s traditional “thirty questions literacy test”—virtually impossible to pass—which had long been used to keep blacks from voting. That same year, his mother Lillian and sister Gloria volunteered to work in Americus at Lyndon Johnson’s election headquarters. Because of his stand on civil rights, Johnson was unpopular in the South. Lillian came out of the headquarters often to find her car smeared with soap, the aerial tied into a knot and threatening messages left on the front seat. Back in Plains, children hurled things at her car and called her “nigger-lover.” And Chip Carter was beaten up at school for wearing an “LBJ” button.

By this time, Miss Lillian was thinking of widening her own horizons. In 1964 she had gone to the Democratic National Convention, then joined a goodwill tour of the Soviet Union and eastern Europe for the State Department. “They were rewarding experiences.” she said, “but over too quick, and soon I was bored again. I’m not a religious fanatic, but I am a Christian, and I was certain there was something important I was intended to do.”

She found out what that was one spring, and seeking Jimmy and Billy out at the warehouse one afternoon, she asked them if they loved her. Jimmy said, “Of course we do, Mama,” but Billy was blunter. “What in hell are you up to now?” So she showed him her application form and told them she had joined the Peace Corps. “Age is no barrier,” the television commercial had said, and now, at sixty-eight, she was on her way to Chicago for orientation and then to India, where she was going to be a nurse. Her sons knew better than to try to stop her.

Back on the home front, Jimmy wrote and supported so much legislation for education, mental health, and consumer reform that in his second term, he was named one of Georgia’s two outstanding state legislators.

Carter made up his mind to run for Congress from his district, the third district of Georgia. His opponent was to be Howard Callaway, the wealthy, articulate young Republican congressman from the district. They had long been competitors: Callaway led Georgia’s Republicans, while Carter was regarded as one of the state’s most promising young Democrats; furthermore, Callaway was a West Point man, and he and Annapolis graduate Carter had a certain tendency to bristle at each other. In the late spring of 1966, Jimmy launched a grassroots campaign after the legislature adjourned, making speeches, meeting voters, asking them how they stood on various issues, returning home late each night with a list of names and addresses of the people he had met. He or Rosalynn or his sister Gloria wrote notes to them all, asking for their vote.

Callaway announced for governor instead of Congress. Later when the Democratic front runner withdrew from the contest, Carter determined to run for governor himself. Only three months remained before the statewide Democratic primary; he had to win that before he could tackle Callaway in the general election in November. For over two years Callaway had been the daily subject of statewide news stories, while Jimmy was scarcely well known in the same way. “Jimmy Who?” he was quickly dubbed by the Atlanta press. But Jimmy thought he could win.

The news of his candidacy gave Georgia Republicans their biggest guffaw in a long time, though it hardly amused Democrats in his home congressional district to see him abandon a campaign that he surely could have won. The first Sunday afternoon that he called his supporters to Atlanta, only a handful appeared. Frantically, he campaigned through Georgia, and gradually those Sunday meetings began to draw more supporters. He was making headway, he could see it. Crippled by lack of money and of volunteer workers, he called upon Rosalynn and their sons and they campaigned actively all over the state.

Nearly 800,000 voters turned out for the Democratic primary, and Jimmy Carter ran third. In forty-two years he had never felt such a crushing sense of disappointment. Deep in debt and thinner than ever, he felt depressed and discouraged.

At church one Sunday Jimmy heard the minister challenge his flock: “If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?” Telling Rosalynn how deeply that question left him shaken, he said he felt he needed to go and manifest his faith, and she understood.

He got involved with a missionary program through his church and went to witness for his faith in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, moving among people, knocking at their doors and greeting them. Jimmy would tell them, “I’m a farmer from Georgia,” and talk quietly of his Christian beliefs. When he returned, Rosalynn had news he had not expected to hear again: she had just learned that she was pregnant.

The inner peace he had regained as a witness for his faith, and as the prospective father of a new baby, had renewed his strength, his energy—and his determination to win the governorship. In the course of the next three weeks, he planned a gubernatorial campaign plan so thorough in its statewide coverage and with such infiltration among all voters that he could not see how it could possibly fail.

He reviewed his list of campaign volunteers and soon set them to the task of collecting, organizing and then actually memorizing what grew within days into a Georgia-wide atlas of county maps. They made an exhaustive study of the previous voting patterns within each county. The results were a code of varicolored plastic tabs and stick pins arranged demographically upon each county’s map.

In the midst of all this Rosalynn—at forty—delivered a perfect baby girl whom they called Amy. “She makes me feel I’m starting young all over again!” Jimmy exclaimed.

Redoubling his zeal, Jimmy organized an eight-county commission to study the techniques of long-range planning and development. Then the commission was expanded state-wide with him as its first state president. With that platform, he knew he could go anywhere in Georgia, speaking and campaigning, and he did just that. Nor was that enough: as a longstanding member of the Plains Lions Club, he became state chairman of the six regional districts containing the 180 Lions Clubs. In small towns like Plains these were the focal point for nearly all political and civic activities. Already prominent in religious and agricultural organizations, he became an official in the statewide March of Dimes.

“Show me a good loser and I’ll show you a loser. I do not intend to lose again!” he pledged to his volunteers. No city or town or hamlet escaped hearing about Senator Jimmy Carter. Rising before dawn, he had his day’s plan on paper by breakfast time. For the rest of the morning he worked at the warehouse, and then after lunch drove away, speaking to sometimes as many as three groups. On the way home he dictated politically useful information into a tape recorder, knowing that Rosalynn would transcribe and file it and write brief notes when necessary. He sometimes found it difficult to believe that the formidable woman who had become the keel of his life had once been the shy nineteen-year-old he had married. He thought that no woman could be any more dependable and direct and firm; yet with their children, and in their own private times together, neither could any woman possibly have been more dear, and sweet, and tender.

With the next primary election’s date looming a year ahead, Jimmy cranked his campaign into high gear. Guided by his color-coded findings posted upon large charts and graphs, he and his family and his staff blanketed the state. They did not, as a ride, stay in hotels or motels, but in the homes of local supporters, both to save money and to get people involved.

As the 1970 primary drew nearer, he was more committed than ever and so was Rosalynn. Jimmy had told her he needed her help on the campaign trail not only as his companion but as a speaker on her own. Rosalynn was at first fearful she’d be a liability. But she tried, because Jimmy had asked her to. He had no idea what a giant step it represented to her. “It was the hardest thing I’d ever had to do in my life.” she admitted later. But after the first ordeal or two, campaigning was almost effortless for Rosalynn. She and Jimmy met workers at the factory gates, pumped hands in department stores, went into beauty shops, barber shops, restaurants, gas stations, school picnics, rodeos, livestock shows.

The staff, the candidate and his family were exhausted as they moved into the final week of the campaign. Carter had proved himself one of the most driving, driven, relentless campaigners the South had ever seen. He alone had made nearly 1,800 speeches; he and Rosalynn had shaken hands with some 600,000 people—more than half of the eligible voters in Georgia. The day of the 1970 gubernatorial election at last arrived and he won it, big.

Calling Georgia’s administrative organization “a tangle of overlapping civil service bureaucracies and patronage fiefs dating back forty years,” promising its massive reorganization, he set about borrowing 100 management experts from industry, government and universities. Their resulting 300 recommendations evoked a howling din of protests while a reorganization program was written. He fought it through the legislature, then in such a grueling senate battle that it was at last by a single vote that he won the radical consolidation of government functions into only twenty-two agencies.

Next challenging the fiscal crisis with what he termed “zero-based budgeting,” Governor Carter required every department head to justify each annual dollar spent for his programs. Among the other efforts and achievements of his one-term administration, he raised the number of significant black state appointees from three to fifty-three; opened the government meaningfully to women; formed a commission for land preservations; vigorously fought air and water pollution; took steps to humanize care for the mentally disturbed; improved prison conditions; organized Georgia’s first narcotic-addiction centers; fought for tough consumer-protection laws and new banking regulations; spearheaded new programs in the area of health care and education; constantly traveled the state listening to citizen complaints—and acting on them.

Rough even on his own staff, he was sometimes stern about responsibility, efficiency, punctuality, brevity. He rejected memos over three pages long, unless they were of the greatest importance. He never wanted to hear anyone give him reasons why anything couldn’t be done. In conferences, he generated conflicts. He listened intently even to heretical advice on any issue. Then he considered what he had heard with what his own knowledge and beliefs and intuitions said, and he made up his mind. Once having done that, he was not apt to change it, ever. Said one of his oldest, closest friends, Georgia Secretary of State Ben Fortson, “He’s stubborn as a south Georgia turtle.”

On February 17, 1974, Carter made Georgia history by hanging portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr. and two other distinguished black Georgians in the state house. Yet, perhaps as memorable as anything during his term was the inaugural speech of the state of Georgia’s seventy-sixth governor. It surprised and even shocked a great many people, but it is well worth quoting now: Our people are our most precious possession. We cannot afford to waste the talents and abilities given by God to one single person. Every adult illiterate, every school dropout, every untrained retarded child is an indictment of us all. Our state pays a terrible and continuing price for these failures. I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. No poor, rural, weak or black person should ever have to bear the additional burden of being deprived of the opportunity of an education, a job, or simple justice.

That the man who spoke those words in the state of Georgia scarcely seven brief years ago has come to the high office he has just assumed is surely one of the most amazing political events of our times. In recent years it has sometimes seemed to the American people as if power goes mainly to the powerful, wealth to those that have no need of it, education to the sons and daughters of the educated. And the old hope that any child might grow up to be President has come to seem a little foolish. Not since the nineteenth century has a Southerner and farmer come to the White House. Knowing, as he does know, that it hurts to be on the losing side, he can, we trust, restore us to our faith that people are the most precious possession of this nation, and that each child and each man and each woman matters, whether black or white. ~ Alex Haley.

(President Jimmy Carter by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in “A New Spirit, A New Commitment, A New America”. © 1977 by the 1977 Inaugural Committee. All Rights Reserved.)

Congressional Black Caucus’ Dinner Remarks • September 24, 1977

I appreciate the chance to come. You’ve probably noticed that I was a little late in arriving. I met Alex Haley outside, and I made the mistake of saying, “Alex, how’s your family?” [Laughter] Unfortunately, he told me. And it took a while to get in. [Laughter]

Alex and I have a lot in common. I just came up a few minutes ago from an afternoon of campaigning in Virginia, and was in Williamsburg right across from where my own folks came to this country, I think 340 years ago, across the river from Jamestown. He and I were both in the Navy. We both were famous enough last year to be interviewed by Playboy magazine. [Laughter] We both wrote a book. Mine was called “Why Not The Best?”; his was. [Laughter] ~ President Jimmy Carter.