(Roots: The Mixing of The Blood was originally published in the October 1976 issue of Playboy Magazine. In addition, it was also published within Alex Haley: The Playboy Interviews by Ballantine Books in July 1993.)

(Roots: The Mixing of The Blood was originally published in the October 1976 issue of Playboy Magazine. In addition, it was also published within Alex Haley: The Playboy Interviews by Ballantine Books in July 1993.)

For 12 years, Alex Haley researched and wrote the story of the seven generations of his family that he would call Roots. It began when Haley, a writer who conducted the first Playboy Interview and many others, was on a playboy assignment in England and first saw the Rosetta stone, the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics. He became curious about some African phrases he remembered hearing from his relatives as a boy in Tennessee and, in particular, the name Kunta Kinte, whom he believed was his African ancestor.

Poring over old records, consulting experts in linguistics, anthropology and genealogy, Haley tracked down every lead until his research finally led him to a village in Gambia. There, in a moment of high drama, the tribal historian, known as a griot, was retelling the story of the village through past generations and came to a day in 1767 when a 17-year-old boy was abducted by white men in the woods near the village and never heard from again His name was Kunta Kinte.

Beginning with life in the village of Juffure, Roots describes Kunta Kinte’s early years, his kidnaping, his transportation in the filthy, hellish hold of a slave ship across the Atlantic and his sale to John Waller, a Virginia planter. Rebellious and fiercely independent, Kunta tried to escape so often that his pursuers chopped off part of his foot as punishment. He eventually married Bell, the plantation cook, who gave birth to a girl named Kizzy.

Bell taught their daughter how to get along with whites and was delighted when, for instance, Kizzy became fast friends with the Waller niece, Missy Anne, who taught her to read and write.

But Kunta remained stubbornly committed to passing along at least some of his African heritage, telling her about Juffure and relating old village customs—such as his method of keeping track of time by dropping pebbles into a gourd. By the early 1800s, the first of Kunta’s descendants to be born in America had grown to be a pretty girl and was living a relatively sheltered life as a house slave.

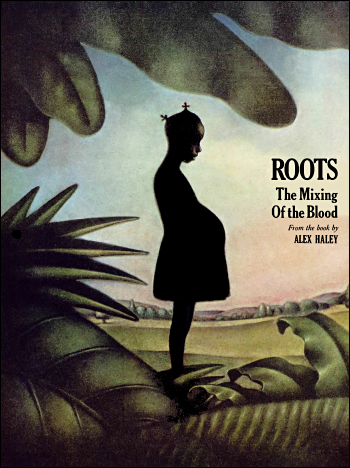

Roots: The Mixing of The Blood

“do i got a gran’ma?” asked Kizzy.

“You got two—my mammy and yo’ mammy’s mammy.”

“How come dey ain’t wid us?”

“Dey don’ know where we is,” said Kunta. “Does you know where we is?” he asked her a moment later.

“We’s in de buggy,” Kizzy said.

“I means where does we live?”

“At Massa Waller’s.”

“An’ where dat is?”

“Dat way,” she said, pointing down the road. Uninterested in their subject, she said, “Tell me some more ’bout dem bugs an’ things where you come from.”

“Well, dey’s big red ants knows how to cross rivers on leafs, dat fights wars an’ marches like a army, an’ builds hills dey lives in dat’s taller than a man.”

“Dey soun’ scary. You step on ’em?”

“Not less’n you has to. Every critter got a right to be here, same as you. Even de grass is live an’ got a soul, jes’ like peoples does.”

“Won’t walk on de grass no mo’, den. I stay in de buggy.”

Kunta smiled. Wasn’t no buggies where I come from. Walked wherever we was goin’. One time I walked four days wid my pappy all de way from Juffure to my uncles’ new village.

“What ‘Joo-fah-ray’?”

“Done tol’ you don’ know how many times, dat where I come from.”

“I thought you was from Africa. Dat Gambia you talks ’bout in Africa?”

“Gambia a country in Africa. Juffure a village in Gambia.”

“Well, where dey at, Pappy?”

“ ’Crost de big water.”

“How big dat big water?”

“So big it take near ’bout four moons to get ‘crost it.”

“Four what?”

“Moons. Like you say ‘months.’ ”

“How come you don’ say months?”

“ ’Cause moons my word fer it.”

“What you call a ‘year’?”

“A rain.”

Kizzy mused briefly.

“How you get ‘crost dat big water?”

“In a big boat.”

“Bigger dan dat rowboat we seen dem fo’ mens fishin’ in?”

“Big ‘nough to hol’ a hunnud mens.”

“How come it don’ sink?”

“I use to wish it woulda.”

“How come?”

“ ’Cause we all so sick seem like we gon’ die anyhow.”

“How you get sick?”

“Got sick from layin’ in our own mess prac’ly on top each other.”

“Why’n’t you go de toilet?”

“De toubob had us chained up.”

“Who ‘toubob’?”

“White folks.”

“How come you chained up? You done sump’n wrong?”

“Was jes’ out in de woods near where I live—Juffure—lookin’ fer a piece o’ wood to make a drum wid, an’ dey grab me an’ take me off.”

“How ol’ you was?”

“Sebenteen.”

“Dey ask yo’ mammy an’ pappy if’n you could go?”

Kunta looked incredulously at her. “Woulda took dem, too, if’n dey could. To dis day, my fam’ly don’ know where I is.”

“You got brothers an’ sisters?”

“Had three brothers. Maybe mo’ by now. Anyways, dey’s all growed up, prob’ly got chilluns like you.”

“We go see dem someday?”

“We cain’t, go nowheres.”

“We’s gon’ somewheres now.”

“Jes’ Massa John’s. We don’ show up, dey have de dogs out at us by sundown.”

“ ’Cause dey be worried ’bout us?”

“ ’Cause we b’longs to dem, jes’ like dese hosses pullin’ us.”

“Like I b’longs to you an’ Mammy?”

“You’s our young’un. Dat diff’rent.”

“Missy Anne say she want me fo’ her own.”

“You ain’t no doll for her to play wid.”

“I plays wid her, too. She done tole me she my bes’ frien’.”

“You cain’t be nobody’s frien’ an’ slave both.”

“How come, Pappy?”

“ ’Cause frien’s don’ own one ‘nother.”

“Don’ Mammy an’ you b’long to one ‘nother? Ain’t y’all frien’s?”

“Ain’t de same. We b’longs to each other ’cause we wants to, ’cause we loves each other.”

“Well. I loves Missy Anne, so I wants to b’long to her.”

“Couldn’t never work out.”

“What you mean?”

“You couldn’t be happy when y’all growed up.”

“Would too. I bet you wouldn’t be happy.”

“You sho’ right ’bout dat!”

“Aw, Pappy. I couldn’t never leave you an’ Mammy.”

“An’ chile, ‘speck we couldn’t never let you go, neither!”

For many years now, Kunta had gotten up every morning before dawn, earlier than anyone else on slave row—so early that some of the others were convinced that “dat African” could see in the dark like a cat. Whatever they wanted to think was fine with him, as long as he was left alone to slip away to the barn, where he would face the first faint streaking of the day prostrated between two large bundles of hay, offering up his daily Suba prayer to Allah. Afterward, by the time he had pitched some hay into the horses’ feed trough, he knew that Bell and Kizzy would be washed, dressed and ready to get things under way in the big house, and the boss field hand, Cato, would be up and out with Ada’s son Noah, who would soon be ringing the bell to wake the other slaves.

Almost every morning, Noah would nod and say “Mornin’ ” with such solemn reserve that he reminded Kunta of the Jaloff people in Africa, of whom it was said that if one greeted you in the morning, he had uttered his last good word for the day. But although they had said little to each other, he liked Noah, perhaps because he reminded Kunta of himself at about the same age—the serious manner, the way he went about his work and minded his own business, the way he spoke little but watched everything. He had often noticed Noah doing a thing that he also did—standing quietly somewhere with his eyes following the rompings of Kizzy and Missy Anne around the plantation. Once when Kunta had been watching from the barn door as they rolled a hoop across the back yard, giggling and screaming, he had been about to go back inside when he saw Noah standing over by Cato’s cabin, also watching. Their eyes met and they looked at each other for a long moment before both turned away. Kunta wondered what Noah had been thinking—and had the feeling that, likewise, Noah was wondering what he was thinking. Kunta knew somehow that they were both thinking the same things.

At ten, Noah was two years older than Kizzy, but that difference wasn’t great enough to explain why the two hadn’t even become friends, let alone playmates, since they were the only slave children on the plantation. Kunta had noticed that whenever they passed near each other, each of them always acted as if he or she had not even seen the other, and he couldn’t figure out why—unless it was because even at their age they had begun to sense the custom that house slaves and field slaves didn’t mix with one another.

Whatever the reason, Noah spent his days out with others in the fields while Kizzy swept, dusted, polished the brass and tidied up the massa’s bedroom every day—for Bell to inspect later with a hickory switch in her hand. On Saturdays, when Missy Anne usually came to call, Kizzy would somehow miraculously manage to finish her chores in half the time it took her every other day, and the two of them would spend the rest of the day playing—excepting at midday if the massa happened to be home for lunch. Then he and Missy Anne would eat in the dining room with Kizzy standing behind them, gently fanning a leafy branch to keep away flies, as Bell shuttled in and out, serving the food and keeping a sharp eye on both girls, having warned them beforehand, “Y’all lemme catch you even thinkin’ ’bout gigglin’ in dere wid Massa, I’ll tan both yo’ hides!”

Kunta by now was pretty much resigned to sharing his Kizzy with Massa Waller, Bell and Missy Anne. He tried not to think about what they must have her doing up there in the big house and he spent as much time as possible in the barn when Missy Anne was around. But it was all he could do to wait until each Sunday afternoon, when church would be over and Missy Anne would go back home with her parents. Later on these afternoons, usually Massa Waller would be either resting or passing the time with company in the parlor, Bell would be off with Aunt Sukey and Sister Mandy at their weekly “Jesus meetin’s”—and Kunta would be free to spend another couple of treasured hours alone with his daughter.

When the weather was good, they’d go walking—usually along the vine-covered fence row where he had gone almost nine years before to think of the name Kizzy for his new girl-child. Out beyond where anyone would be likely to see them, Kunta would clasp Kizzy’s soft little hand in his own as, feeling no need to speak, they would stroll down to a little stream and, sitting closely together beneath a shade tree, they would eat whatever Kizzy had brought along from the kitchen—usually cold buttered biscuits filled with his favorite blackberry preserves. Then they would begin talking.

Mostly he’d talk and she’d interrupt him constantly with questions, most of which would begin “How come….” But one day Kunta didn’t get to open his mouth before she piped up eagerly, “You wanna hear what Missy Anne learned me yestiddy?”

He didn’t care to hear of anything having to do with that giggling white creature, but not wishing to hurt his Kizzy’s feelings, he said, “I’m listenin’.”

“ ’Peter, Peter, punkin eater,’ ” she recited, “ ’had a wife an’ couldn’ keep ‘er; put ‘er in a punkin shell, dere he kep’ ‘er very well….’ ”

“Dat it?” he asked.

She nodded. “You like it?”

He thought it was just what he would have expected from Missy Anne: completely asinine. “You says it real good,” he hedged.

“Bet you can’t say it good as me,” she said with a twinkle.

“Ain’t tryin’ to!”

“Come on, Pappy, say it fo’ me jes’ once.”

“Git ‘way from me wid dat mess!” He sounded more exasperated than he really was. But she kept insisting and finally, feeling a bit foolish that his Kizzy was able to twine him around her finger so easily, he made a stumbling effort to repeat the ridiculous lines—just to make her leave him alone, he told himself.

Before she could urge him to try the rhyme again, the thought flashed to Kunta of reciting something else to her—perhaps a few verses from the Koran, so that she might know how beautiful they could sound—then he realized such verses would make no more sense to her than “Peter, Peter” had to him. So he decided to tell her a story. She had already heard about the crocodile and the little boy, so he tried the one about the lazy turtle that talked the stupid leopard into giving him a ride by pleading that he was too sick to walk.

“Where you hears all dem stories you tells?” Kizzy asked when he was through.

“Heared ’em when I was yo’ age—from a wise ol’ gran’mammy name Nyo Boto.” Suddenly, Kunta laughed with delight, remembering: “She was bald-headed as a egg! Didn’t have no teeth, neither, but dat sharp tongue o’ her’n sho’ made up fer it! Loved us young’uns like her own, though.”

“She ain’t had none of ‘er own?”

“Had two when she was real young, long time ‘fo’ she come to Juffure. But dey got took away in a fight ‘tween her village an’ ‘nother tribe. Reckon she never got over it.”

Kunta fell silent, stunned with a thought that had never occurred to him before: The same thing had happened to Bell when she was young. He wished he could tell Kizzy about her two half sisters, but he knew it would only upset her—not to mention Bell, who hadn’t spoken of it since she told him of her lost daughters on the night of Kizzy’s birth. But hadn’t he—hadn’t all of those who had been chained beside him on the slave ship been torn away from their own mothers? Hadn’t all the countless other thousands who had come before and—since?

“Dey brung us here naked!” he heard himself blurting. Kizzy jerked up her head, staring; but he couldn’t stop. “Even took our names away. Dem like you gits borned here don’ even know who dey is! But you jes’ much Kinte as I is! Don’ never fo’git dat! Us’n’s fo’fathers was traders, travelers, holy men all de way back hunnuds o’ rains into dat lan’ call Ol’ Mali! You unnerstan’ what I’m talkin’ ’bout, chile?”

“Yes, Pappy,” she said obediently, but he knew she didn’t. He had an idea. Picking up a stick, smoothing a place in the dirt between them, he scratched some characters in Arabic.

“Dat my name—Kun-ta Kin-te,” he said, tracing the characters slowly with his finger.

She stared, fascinated. “Pappy, now do my name. He did. She laughed. “Dat say Kizzy?” He nodded. “Would you learn me to write like you does?” Kizzy asked.

“Wouldn’t be fittin’,” said Kunta sternly.

“Why not?” She sounded hurt.

“In Africa, only boys learns how to read an’ write. Girls ain’t got no use fer it—over here, neither.”

“How come Mammy can read an’ write, den?”

Sternly, he said, “Don’ you be talkin’ dat! You hear me? Ain’t nobody’s business! White folks don’ like none us doin’ no readin’ or writin’!”

“How come?”

“ ’Cause dey figgers less we knows, less troubles we makes.”

“I wouldn’t make no trouble,” she said, pouting.

“If’n we don’ hurry up an’ git back to de cabin, yo’ mammy gon’ make trouble fer us both.”

Kunta got up and started walking, then stopped and turned, realizing that Kizzy was not behind him. She was still by the bank of the stream, gazing at a pebble she had seen.

“Come on, now, it’s time to go.” She looked up at him and he walked over and reached out his hand. “Tell you what,” he said. “You pick up dat pebble an’ bring it ‘long an’ hide it somewheres safe, an’ if’n you keeps yo’ mouth shet ’bout it, nex’ new-moon mornin’ I let you drop it in my gourd.”

“Oh, Pappy!” She was beaming.

Just after Christmas of 1803, the winds blew the snow into deep, feathery drifts until in places the roads were hidden and impassable for all but the biggest wagons. When the massa went out—in response to only the most desperate summons—he had to ride on one of the horses, and Kunta stayed behind, busily helping Cato, Noah and the fiddler keep the driveway clear and chop wood to keep all of the fireplaces steadily going.

Cut off as they were—even from Massa Waller’s Gazette, which had stopped arriving about a month before with the first big snow—the slave-row people were still talking about the last bits of news that had gotten through to them: how pleased the white massas were with the way President Jefferson was “runnin’ the gubmint,” despite the massas’ initial reservations toward his views regarding slaves. Since taking office, President Jefferson had reduced the size of the Army and Navy, lowered the public debt, even abolished the personal-property tax—that last act, the fiddler said, particularly having impressed those of the massa class with his greatness.

But Kunta said that when he had made his last trip to the county seat before they had gotten snowed in, white folks had seemed to him even more excited about President Jefferson’s purchase of the huge Louisiana Territory for but three cents an acre. “What I likes ’bout it,” he said, “ ’cordin’ to what I heared, dat Massa Napoleon had to sell it so cheap cause he in sich hot water in France over what it cost ‘im in money, ‘long wid fifty thousan’ Frenchmans got killed or died ‘fo’ dey beat dat Toussaint in Haiti.”

They were all still warming themselves in the glow of that thought a later afternoon when a black rider arrived amid a snowstorm with an urgently ill patient’s message for the massa—and another of dismal news for the slave row: In a damp dungeon on a remote French mountain where Napoleon had sent him, Haiti’s General Toussaint had died of cold and starvation.

Three days later, Kunta was still feeling stricken and depressed when he trudged back to the cabin for a mug of hot soup and, stamping snow from his shoes, then entering pulling off his gloves, he found Kizzy stretched out on her pallet in the front room, her face drawn and frightened. “She feelin’ po’ly,” was the explanation that Bell offered as she strained a cup of her herb tea and ordered Kizzy to sit up and drink it. Kunta sensed that something was being kept from him; then when he was a few more minutes there in the overwarm, tightly closed, mud-chinked cabin, his nostrils helped him guess that Kizzy was experiencing her first time of the bloodiness.

He had watched his Kizzy growing and maturing almost every day now for nearly 13 rains, and he had lately come to accept within himself that her ripening into womanhood would be only a matter of time: yet somehow he felt completely unprepared for this pungent evidence. After another day abed, though, the hardy Kizzy was back up and about in the cabin, then back at work in the big house—and it was as if overnight that Kunta actually noticed for the first time how his girl-child’s previously narrow body had budded. With a kind of embarrassed awe, he saw that somehow she had gotten mango-sized breasts and that her buttocks had begun to swell and curve. She even seemed to be walking in a less girlish way. Now, whenever he went through the bedroom separator curtain into the front room, where Kizzy slept, he began to avert his eyes: and whenever Kizzy happened not to be clothed fully, he sensed that she felt the same.

In Africa now, he thought—Africa had sometimes seemed so distantly in the past—Bell would be instructing Kizzy in how to make her skin shine, using shea-tree butter, and how to fashionably, beautifully blacken her mouth, palms and soles, using the powdered crust from the bottoms of cooking pots. And Kizzy would at her present age already be starting to attract men who were seeking for themselves a finely raised, well-trained, virginal young wife. Kunta felt jolted even by the thought of some man’s foto entering Kizzy’s thighs; then he felt better after reasssuring himself that this would happen only after a proper wedding. In his homeland at this time, as Kizzy’s fa, he would be assuming his responsibility to appraise very closely the personal qualities as well as the family backgrounds of whatever men began to show marriageable interest in Kizzy—in order to select the most ideal of them for her; and he would also be deciding now what proper bride price would be asked for her hand.

But after a while, as he continued to shovel snow along with the fiddler, young Noah and Cato, Kunta found himself feeling increasingly ridiculous that he was even thinking about these African customs and traditions anymore: for not only would they never be observed here, nor respected—indeed, he would also be hooted at if he so much as mentioned them, even to other blacks. And, anyway, he couldn’t think of any likely, well-qualified suitor for Kizzy who was of proper marriageable age—between 30 and 35 rains—but there he was, doing it again! He was going to have to force himself to start thinking along lines of the marrying customs here in the toubob’s country, where girls generally married—”jumpin’ de broom,” it was called—someone who was around their age.

Immediately, then, Kunta began thinking about Noah. He had always liked the boy. At 15, two years older than Kizzy, Noah seemed to be no less mature, serious and responsible than he was big and strong. The more Kunta thought about it, the only thing he could find lacking with Noah, in fact, was that he had never seemed to show the slightest personal interest in Kizzy—not to mention that Kizzy herself seemed to act as if Noah didn’t exist. Kunta pondered: Why weren’t they any more interested than that in each other, at the least in being friends? After all, Noah was very much as he himself had been as a young man, and therefore, he was highly worthy of Kizzy’s attention, if not her admiration. He wondered: Wasn’t there something he could do to influence them into each other’s paths? But then Kunta sensed that probably would be the best way to ensure their never getting together. He decided, as usual, that it was wisest that he mind his own business—and, as he had heard Bell put it, with “de sap startin’ to rise” within the young pair of them who were living right there in the same slave row, he privately would ask if Allah would consider helping nature take its course.

It was a week after Kizzy’s 16th birthday, the early morning of the first Monday of October, when the slave-row field hands were gathering, as usual, to leave for their day’s work, when someone asked curiously, “Where Noah at?” Kunta, who happened to be standing nearby, talking to Cato, knew immediately that he was gone. He saw heads glancing around, Kizzy’s among them, straining to maintain a mask of casual surprise. Their eyes met—she had to look away.

“Thought he was out here early wid you,” said Noah’s mother, Ada, to Cato.

“Naw, I was aimin’ to give ‘im de debbil fo’ sleepin’ late,” said Cato.

Cato went banging his fist on the closed door of the cabin once occupied by the old gardener but which Noah had inherited recently on his 18th birthday. Jerking the door open, Cato charged inside, shouting angrily, “Noah!” He came out looking worried. “Ain’t like ‘im,” he said quietly. Then he ordered them all to go quickly and search their cabins, the toilet, the storerooms, the fields.

When they returned to their cabin, Kizzy burst into tears the moment she got inside: Kunta felt helpless and tongue-tied. But without a word, Bell went over to the table, put her arms around her sobbing daughter and pulled her head against her stomach.

Tuesday morning came, still with no sign of Noah, and Massa Waller ordered Kunta to drive him to the county seat, where he went directly to the Spotsyivania jailhouse. After about half an hour, he came out with the sheriff, ordering Kunta brusquely to tie the sheriff’s horse behind the buggy and then to drive them home. “We’ll be dropping the sheriff off at the Creek Road,” said the massa.

“So many niggers runnin’ these days, can’t hardly keep track—they’d ruther take their chances in the woods than get sold down South.” The sheriff was talking from when the buggy started rolling.

“Since I’ve had a plantation,” said Massa Waller, “I’ve never sold one of mine unless my rules were broken, and they know that well.”

“But it’s mighty rare niggers appreciate good masters, doctor, you know that,” said the sheriff. “You say this boy around eighteen? Well, I’d guess if he’s like most field hands his age, there’s fair odds he’s tryin’ to make it North.” Kunta stiffened. “If he was a house nigger, they’re generally slicker, faster talkers, they like to try passin’ themselves off as free niggers or tell the road patrollers they’re on their master’s errands and lost their traveling passes, tryin’ to make it to Richmond or some other big city, where they can easier hide among so many niggers and maybe find jobs.” The sheriff paused. “Besides his mammy on your place, this boy of yours got any other kin livin’ anywheres he might be tryin’ to get to?”

“None that I know of.”

“Well, would you happen to know if he’s got some gal somewheres, because these young bucks get their sap risin’, they’ll leave your mule in the field and take off.”

“Not to my knowledge,” said the massa. “But there’s a gal on my place, my cook’s young’un, she’s still fairly young, fifteen or sixteen, if I guess correctly. I don’t know if they’ve been haystacking or not.”

Kunta nearly quit breathing.

“I’ve known ’em to have pickaninnies at the age of twelve!” the sheriff chortled. “Plenty of these young nigger wenches even draw white men, and nigger boys’ll do anything!”

Through churning outrage, Kunta heard Massa Waller’s abrupt chilliness. “I have the least possible personal contact with my slaves and neither know nor concern myself regarding their personal affairs!”

“Yes, yes, of course,” said the sheriff quickly.

Saturday morning after breakfast, Kunta was currycombing a horse outside the barn when he thought he heard Cato’s whippoorwill whistle. Cocking his head, he heard it again. He tied the horse quickly to a nearby post and cripped rapidly up the path to the cabin. From its front window he could see almost from where the main road intersected with the big-house driveway. He knew that Cato’s call had also alerted Bell and Kizzy inside the big house.

Then he saw the wagon rolling down the driveway—and with surging alarm recognized the sheriff at the reins. Merciful Allah, had Noah been caught? As Kunta watched the sheriff dismount, his long-trained instincts tugged at him to hasten out and provide the visitor’s winded horse with water and a rubdown; but it was as if he were paralyzed where he stood, staring from the cabin window, as the sheriff hurried up the big-house front steps two at a time.

Only a few minutes passed before Kunta saw Bell almost stumbling out the back door. She started running—and Kunta was seized with a horrible premonition the instant before she nearly snatched their cabin door off its hinges.

Her face was twisted, tear-streaked. “Sheriff an’ Massa talkin’ to Kizzy!” she squealed.

The words numbed him. For a moment, he just stared disbelievingly at her, but then, violently seizing and shaking her, he demanded, “What he want?”

Her voice rising, choking, breaking, she managed to tell him that the sheriff was scarcely in the house before the massa had yelled for Kizzy to come from tidying his room upstairs. “When I heard ‘im holler at her from de kitchen, I flew to git in de drawin’-room hallway, where I always listens from, but I couldn’t make out nothin’ clear ‘cept he was mighty mad”—Bell gasped and swallowed. “Den heard Massa ringin’ my bell, an’ I run back to look like I was comin’ from de cookhouse. But Massa was awaitin’ in de do’way, wid his han’ holdin’ de knob behin’ ‘im. Ain’t never seed ‘im look like he did at me. He tol’ me col’ as ice to git out’n de house an’ stay out till I’m sent for!” Bell moved to the small window, staring at the big house, unable to believe that what she had just said had really happened. “Lawd Gawd, what in de worl’ sheriff want wid my chile?” she asked incredulously.

Kunta’s mind was clawing desperately for something to do. Could he rush out to the fields, at least to alert those who were chopping there? But his instincts said that anything could happen with him gone.

As Bell went through the curtain, into their bedroom, beseeching Jesus at the top of her lungs, Kunta could barely restrain himself from raging in and yelling that she must see now what he had been trying to tell her for nearly 40 rains about being so gullible, deluded and deceived about the goodness of the massa—or any other toubob.

“Gwine back in dere!” cried Bell suddenly. She came charging through the curtain and out the door.

Kunta watched as she disappeared inside the kitchen. What was she going to do? He ran out after her and peered in through the screen door. The kitchen was empty and the inside door was swinging shut. He went inside, silencing the screen door as it closed, and tiptoed across the kitchen. Standing there with one hand on the door, the other clenched, he strained his ears for the slightest sound—but all he could hear was his own labored breathing.

Then he heard: “Massa?” Bell had called softly. There was no answer.

“Massa?” she called again, louder, sharply.

He heard the drawing-room door open.

“Where my Kizzy, Massa?”

“She’s in my safekeeping,” he said stonily. “We’re not having another one running off.”

“I jes’ don’ understan’ you, Massa.” Bell spoke so softly that Kunta could hardly hear her. “De chile ain’t been out’n yo’ yard, hardly.”

The massa started to say something, then stopped. “It’s possible you really don’t know what she’s done,” he said. “The boy Noah has been captured, but not before severely knifing the two road patrolmen who challenged a false traveling pass he was carrying. After being subdued by force, he finally confessed that the pass had been written not by me but by your daughter. She has admitted it to the sheriff.”

There was silence for a long, agonizing moment, then Kunta heard a scream and running footsteps. As he whipped open the door, Bell came bolting past him—shoving him aside with the force of a man—and out the back door. The hall was empty, the drawing-room door shut. He ran out after her, catching up with her at the cabin door.

“Massa gon’ sell Kizzy, I knows it!” Bell started screaming, and inside him something snapped.

“Gwine git her!” he choked out, cripping back toward the big house and into the kitchen as fast as he could go, with Bell not far behind. Wild with fury, he snatched open the inside door and went charging down the unspeakably forbidden hallway.

The massa and the sheriff spun with disbelieving faces as the drawing-room door came jerking open. Kunta halted there abruptly, his eyes burning with murder. Bell screamed behind him, “Where our baby at? We come to git her!”

Kunta saw the sheriff’s right hand sliding toward his holstered gun as the massa seethed. “Get out!”

“You niggers can’t hear?” The sheriffs hand was withdrawing the pistol and Kunta was tensed to plunge for it—just as Bell’s voice trembled behind him “Yassa”—and he felt her desperately pulling his arm. Then his feet were moving backward through the doorway—and suddenly the door was slammed behind them, a key clicking sharply in the lock.

As Kunta crouched with his wife in the hall, drowning in his shame, they heard some tense, muted conversation between the massa and the sheriff . . . then the sound of feet moving, scuffling faintly . . . then Kizzy’s crying and the sound of the front door slamming shut.

“Kizzy! Kizzy chile! Lawd Gawd, don’ let ’em sell my Kizzy!” As she burst out the back door with Kunta behind her, Bell’s screams reached away out to where the field hands were, who came racing. Cato arrived in time to see Bell screeching insanely, springing up and down with Kunta bear-hugging her to the ground. Massa Waller was descending the front steps ahead of the sheriff, who was hauling Kizzy after him—weeping and jerking herself backward—at the end of a chain.

“Mammy! Maaaaamy!” Kizzy screamed.

Bell and Kunta leaped up from the ground and went raging around the side of the house like two charging lions. The sheriff drew his gun and pointed it straight at Bell: She stopped in her tracks. She stared at Kizzy. Bell tore the question from her throat: “You done dis thing deys says?” They all watched Kizzy’s agony as her reddened, weeping eyes gave her answer in a mute way—darting imploringly from Bell and Kunta to the sheriff and the massa—but she said nothing.

“Oh, my Lawd Gawd!” Bell shrieked. “Massa, please have mercy! She ain’t meant to do it! She ain’t knowed what she was doin’! Missy Anne de one teached ‘er to write!”

Massa Waller spoke glacially. “The law is the law. She’s broken my rules. She’s committed a felony. She may have aided in a murder. I’m told one of those white men may die.”

“Ain’t her cut de man, Massa! Massa, she worked for you ever since she big ‘nough to carry yo’ slop jar! An’ I done cooked an’ waited on you han’ an’ foot over forty years, an’ he”—gesturing at Kunta, she stuttered—”he done drive you eve’ywhere you been for near ’bout dat long. Massa, don’ all dat count for sump’n?”

Massa Waller would not look directly at her. “You were doing your jobs. She’s going to be sold—that’s all there is to it.”

“Jes’ cheap, low-class white folks splits up families!” shouted Bell. “You ain’t dat kine!”

Angrily, Massa Waller gestured to the sheriff, who began to wrench Kizzy roughly toward the wagon.

Bell blocked their path. “Den sell me an’ ‘er pappy wid ‘er! Don’ split us up!”

“Get out of the way!” barked the sheriff, roughly shoving her aside.

Bellowing, Kunta sprang forward like a leopard, pummeling the sheriff to the ground with his fists.

“Save me, Fa!” Kizzy screamed. He grabbed her around the waist and began pulling frantically at her chain.

When the sheriff’s pistol butt crashed above his ear, Kunta’s head seemed to explode as he crumpled to his knees. Bell lunged toward the sheriff, but his outflung arm threw her off balance and she fell heavily as he dumped Kizzy into the back of his wagon and snapped a lock on her chain. Leaping nimbly onto the seat, the sheriff lashed the horse, whose forward jerk sent the wagon lurching as Kunta clambered up. Dazed, head pounding, ignoring the pistol, he went scrambling after the wagon as it gathered speed.

“Missy Anne!… Missy Annnnnnne!” Kizzy was screeching it at the top of her voice. “Missy Annnnnnnnnnnnnnnnne!” Again and again, the screams came: they seemed to hang in the air behind the wagon swiftly rolling toward the main road.

When Kunta began stumbling, gasping for breath, the wagon was a half mile away when he halted, for a long time he stood looking after it, until the dust had settled and the road stretched empty as far as he could see.

The massa turned and walked very quickly with his head down back into the house, past Bell huddled sobbing by the bottom step. As if Kunta were sleepwalking, he came cripping slowly back up the driveway—when an African remembrance flashed into his mind and, near the front of the house, he bent down and started peering around. Determining the clearest prints that Kizzy’s bare feet had left in the dust, scooping up the double handful containing those footprints, he went rushing toward the cabin: The ancient forefathers said that precious dust kept in some safe place would ensure Kizzy’s return to where she had made the footprints. He burst through the cabin’s open door, his eyes sweeping the room and falling upon his gourd containing his pebbles on a shelf. Springing over there, in the instant before opening his cupped hands to drop in the dirt, suddenly he knew the truth: His Kizzy was gone; she would not return. He would never see his Kizzy again.

His face contorting, Kunta flung his dust toward the cabin roof. Tears bursting from his eyes, snatching his heavy gourd up high over his head, his mouth wide in a soundless scream, he hurled the gourd down with all his strength and it shattered against the packed-earth floor, his 662 pebbles representing each month of his 55 rains flying out, ricocheting wildly in all directions.

Weak and dazed, Kizzy lay in the darkness, on some burlap sacks, in the cabin where she had been pushed when the mule cart arrived shortly after dusk. She wondered vaguely what time it was; it seemed that night had gone on forever. She began tossing and twisting, trying to force herself to think of something—anything—that didn’t terrify her. Finally, for the 100th time, she tried to concentrate on figuring out how to get “up Nawth,” where, she had heard so often, black people could find freedom if they escaped. If she went the wrong way, she might wind up “Deep Souf,” where people said massas and overseers were even worse than Massa Waller. Which way was “nawth”? She didn’t know. I’m going to escape, anyway, she swore bitterly.

It was as if a pin pricked her spine when she heard the first creaking of the cabin door. Springing upright and backward in the dark, she saw the figure entering furtively, with a cupped hand shielding a candle’s flame. Above it she recognized the face of the white man who had purchased her, and she saw that his other hand was holding up a shorthandled whip, cocked ready for use. But it was the glazed leer on the white man’s face that froze her where she stood.

“Rather not have to hurt you none,” he said, the smell of his liquored breath nearly suffocating her. She sensed his intent. He wanted to do with her what Pappy did with Mammy when she heard strange sounds from their curtained-off room after they thought she was asleep. He wanted to do what Noah had urged her to do when they had gone walking down along the fence row, and which she almost had given in to, several times, especially the night before he had left, but he had frightened her too much when he exclaimed hoarsely, “I wants you wid my baby!” She thought that this white man must be insane to think that she was going to permit him to do that with her.

“Ain’t got no time to play wit you now!” The white man’s words were slurred. Kizzy’s eyes were judging how to bolt past him to flee into the night—but he seemed to read that impulse, moving a little bit sideways, not taking his gaze off her as he leaned over and tilted the candle to drain its melted wax onto the seat of the cabin’s single broken chair, then the small flame flickered upright. Inching slowly backward, Kizzy felt her shoulders brushing the cabin’s wall. “Ain’t you got sense enough to know I’m your new massa?” He watched her, grimacing some kind of a smile. “You a fair-lookin’ wench. Might even set you free, if I like you enough—”

When he sprang, seizing Kizzy, she wrenched loose, shrieking, as with an angry curse he brought the whip cracking down across the back of her neck. “I’ll take the hide off you!” Lunging like a wild woman, Kizzy clawed at his contorted face, but slowly he forced her roughly to the floor. Pushing back upward, she was shoved down again. Then the man was on his knees beside her, one of his hands choking back her screams—”Please, Massa, please!”—the other stuffing dirty burlap sacking into her mouth until she gagged. As she flailed her arms in agony and arched her back to shake him off, he banged her head against the floor, again, again, again, then began slapping her—more and more excitedly—until Kizzy felt her dress being snatched upward, her undergarments being ripped. Frantically thrashing, the sack in her mouth muffling her cries, she felt his hands fumbling upward between her thighs, finding, fingering her private parts, squeezing and spreading them. Striking her another numbing blow, the man jerked down his suspenders, made motions at his trousers’ front. Then came the searing pain as he forced his way into her, and Kizzy’s senses seemed to explode. On and on it went, until finally she lost consciousness.

In the early dawn, Kizzy blinked her eyes open. She was engulfed in shame to find a young black woman bending over her and sponging her private parts gently with a rag and warm, soapy water. When Kizzy’s nose told her that she had also soiled herself, she shut her eyes in embarrassment, soon feeling the woman cleaning her there as well. When Kizzy slitted her eyes open again, she saw that the woman’s face seemed as expressionless as if she were washing clothes, as if this were but another of the many tasks she had been called upon to perform in her life. Finally laying a clean towel over Kizzy’s loins, she glanced up at Kizzy’s face. “Reckon you ain’t feel like talkin’ none now,” the woman said quietly, gathering up the dirty rags and her water pail, preparing to leave. Clutching these things in the crook of one arm, she bent again and used her free hand to draw up a burlap sack to cover most of Kizzy’s body. “ ’Fo long, I bring you sump’n to eat,” she said, and went on out the cabin door.

Kizzy lay there feeling as if she were suspended in midair. She tried to deny to herself that the unspeakable, unthinkable thing had really happened, but the lancing pains of her torn privates reminded her that it had. She felt a deep uncleanness, a disgrace that could never be erased. She tried shifting her position, but the pains seemed to spread. Holding her body still, she clutched the sack tightly about her, as if somehow to cocoon herself against any more outrage, but the pains grew worse.

Kizzy’s mind raced back across the past four days and nights. She could still see her parents’ terrified faces, still hear their helpless cries as she was rushed away. She could still feel herself struggling to escape from the white trader whom the Spotsylvania County sheriff had turned her over to; she had nearly slipped free after pleading that she had to relieve herself. Finally, they had reached some small town where—after long, bitterly angry haggling—the trader at least had sold her to this new massa, who had awaited the nightfall to violate her. Mammy! Pappy! If only screaming for them could reach them—but they didn’t even know where she was. And who knows what might have happened to them? She knew that Massa Waller would never sell anyone he owned “less’n dey breaks his rules.” But in trying to stop the massa from selling her, they must have broken a dozen of those rules.

And Noah, what of Noah? Somewhere beaten to death? Again, it came back to Kizzy vividly. Noah demanding angrily that to prove her love, she must use her writing ability to forge a traveling pass for him to show if he should be seen, stopped and questioned by patrollers or any other suspicious whites. She remembered the grim determination etched on his face as he pledged to her that once he got up North, with just a little money saved from a job he would quickly find, “Gwine steal back here an’ slip you Nawth, too, fo’ de res’ our days togedder.” She sobbed anew. She knew she would never see him again. Or her parents. Unless—

Her thoughts leaped with a sudden hope! Missy Anne had sworn since girlhood that when she married some handsome, rich young massa, Kizzy alone must be her personal maid, later to care for the houseful of children. Was it possible that when she found out Kizzy was gone, she had gone screaming, ranting, pleading to Massa Waller? Missy Anne could sway him more than anyone else on earth! Could the mass a have sent out some men searching for the slave dealer, to learn where he had sold her, to buy her back?

But soon now a new freshet of grief poured from Kizzy. She realized that the sheriff knew exactly who the slave dealer was; they would certainly have traced her by now! She felt even more desperately lost, even more totally abandoned. Later, when she had no more tears left to shed, she lay imploring God to destroy her, if He felt she deserved all this, just because she loved Noah. Feeling some slickness seeping between her upper legs, Kizzy knew that she was continuing to bleed. But the pain had subsided to a throbbing.

When the cabin door came creaking open again, Kizzy had sprung up and was rearing backward against the wall before she realized that it was the woman. She was carrying a steaming small pot, with a bowl and spoon, and Kizzy slumped back down onto the dirt floor as the woman put the pot on the table, then spooned some food into the bowl, which she placed down alongside Kizzy. Kizzy acted as if she saw neither the food nor the woman, who squatted beside her and began talking as matter-of-factly as if they had known each other for years.

“I’se de big-house cook. My name Malizy. What you’n?”

Finally, Kizzy felt stupid not to answer. “It Kizzy, Miss Malizy.”

The woman made an approving grunt. “You sounds well raised.” She glanced at the untouched stew in the bowl. “I reckon you know you let vittles git cold dey don’t do you no good.” Miss Malizy sounded almost like Sister Mandy or Aunt Sukey.

Hesitantly picking up the spoon, Kizzy tasted the stew, then began to eat some of it, slowly.

“How ol’ you is?” asked Miss Malizy.

“I’se sixteen, ma am.”

“Massa boun’ for hell jes’ sho’s he born!” exclaimed Miss Malizy, half under her breath. Looking at Kizzy, she said, “Jes’ well’s to tell you Massa one dem what loves nigger womens, ‘specially young’uns like you is. He use to mess wid me, I ain’t but roun’ nine years older’n you, but he quit after he brung Missy here an’ made me de cook, workin’ right dere in de house where she is, thanks be to Gawd!” Miss Malizy grimaced. “Speck you gwine be seem’ ‘un in here regular.”

Seeing Kizzy’s hand fly to her mouth, Miss Malizy said, “Honey, you jes’ well’s realize you’s a nigger woman. De kind of white man Massa is, you either gives in or he gwine make you wish you had, one way or ‘nother. An’ lemme tell you, dis massa a mean thing if you cross ‘im. Fact, ain’t never knowed nobody git mad de way he do. Ever’thin’ can be gwine ‘long jes’ fine, den let jes’ anythin’ happen dat rile ‘im,” Miss Malizy snapped her fingers, “quick as dat, he can fly red hot an’ ack like he done gon’ crazy!”

Kizzy’s thoughts were racing. Once darkness fell, before he came again, she must escape. But it was as if Miss Malizy read her mind. “Don’t you even start thinkin’ ’bout runnin’ nowhere, honey! He jes’ have you hunted down wid dem blood dogs, an’ you in a worser mess. Jes’ calm yo’self. De next fo’, five days he ain’t gon’ be here nohow. Him an’ his ol’ nigger chicken trainer already done left for one dem big chicken fights halfway ‘crost de state.” Miss Malizy paused. “Massa don’t care ’bout nothin’ much as dem fightin’ chickens o’ his’n.”

She went on talking nonstop—about how the massa, who had grown to adulthood as a po’ cracker, bought a 25-cent raffle ticket that won him a good fighting rooster, which got him started on the road to becoming one of the area’s more successful gamecock owners.

Kizzy finally interrupted. “Don’ he sleep wid his missis?”

“Sho’ he do!” said Miss Malizy. “He jes’ love womens. You won’t never see much o’ her, ’cause she scairt to death o’ ‘im, an’ she keep real quiet an’ stay close. She whole lot younger’n he is; she was jes’ fo’teen, same kind of po’ cracker he was, when he married her an’ brung her here. But she done foun’ out he don’t care much for her as he do his chickens.” As Miss Malizy continued talking about the massa, his wife and his chickens, Kizzy’s thoughts drifted away once again to thoughts of escape.

“Gal! Is you payin’ me ‘tention?”

“Yes’m,” she replied quickly.

Miss Malizy’s frown eased. “Well, I specks you better, since I’se ‘quaintin’ you wid where you is!”

Briefly she studied Kizzy. “Where you come from, anyhow?” Kizzy said from Spotsylvania County, Virginia. “Ain’t never heared of it! Anyhow, dis here’s Caswell County in North Ca’liny.” Kizzy’s expression showed that she had no idea where that was, though she had often heard of North Carolina, and she had the impression that it was somewhere near Virginia.

“Look here, does you even know Massa’s name?” asked Miss Malizy. Kizzy looked blank. “Him’s Massa Tom Lea.” She reflected a moment. “Reckon now dat make you Kizzy Lea.”

“My name Kizzy Walter!” Kizzy exclaimed in protest. Then, with a flash, she remembered that all of this had happened to her at the hands of Massa Waller, whose name she bore, and she began weeping.

“Don’t take on so, honey!” exclaimed Miss Malizy. “You sho’ knows niggers takes whoever’s dey massa’s name. Nigger names don’t make no difference nohow, jes’ sump’n to call ’em.”

Kizzy said, “My pappy’s real name Kunta Kinte. He a African.”

“You don’t say!” Miss Malizy appeared taken aback. “I’se heared my great-gran’daddy was one dem Africans, too! My mammy say her mammy told her he was blacker’n tar, wid scars zigzaggin’ down both cheeks. But my mammy never say his name.” Miss Malizy paused. “You know yo’ mammy, too?”

“ ’Cose I does. My mammy name Bell. She a big-house cook like you is. An’ my pappy drive de massa’s buggy—leas’ he did.”

“You jes’ come from bein’ wid yo’ mammy an’ pappy both?” Miss Malizy couldn’t believe it. “Lawd, ain’t many us gits to know both our folks ‘fo’ somebody git sol’ away!”

Sensing that Miss Malizy was preparing to leave, suddenly dreading being left alone again, Kizzy sought a way to extend the conversation. “You talks a whole lot like my mammy,” she offered.

Miss Malizy seemed startled, then very pleased. “I specks she a good Christian woman like I is.”

Hesitantly, Kizzy asked something that had crossed her mind. “What kine of work dey gwine have me doin’ here, Miss Malizy?”

Miss Malizy seemed astounded at the question. “What you gon’ do?” she demanded. “Massa ain’t tol’ you how many niggers here?” Kizzy shook her head. “Honeychile, you makin’ zactly five! An’ dat’s countin’ Mingo, de ol’ nigger dat live down ‘mongst de chickens. So it’s me cookin’, washin’ an’ housekeepin’, an’ Sister Sarah an’ Uncle Pompey workin’ in de fiel’, where you sho’ gwine go, too—dat you is!”

Miss Malizy’s brows lifted at the dismay on Kizzy’s face. “What work you done where you was?”

“Cleanin’ in de big house an’ helpin’ my mammy in de kitchen,” Kizzy answered in a faltering voice.

“Figgered sump’n like dat when I seen dem soft hands of your’n! Well, you sho’ better git ready for some calluses an’ corns soon’s Massa git back!” Miss Malizy then seemed to feel that she should soften a bit. “Po’ thing! Listen here to me, you been used to one dem rich massa’s places. But dis here one dem po’ crackers what scrabbled an’ scraped till he got holt a li’l lan’ an’ built a house dat ain’t nothin’ but a big front to make ’em look better off dan dey is. Plenty crackers like dat roun’ here. Dey got a sayin’, ‘Farm hundred acres wid fo’ niggers.’ Well, he too tight to buy even dat many. But he finally had to see wasn’t no way jes’ Uncle Pompey an’ Sister Sarah could farm much as he like to plant, an’ he had to git somebody else. Dat’s how come he bought you.” Miss Malizy paused. “You know how much you cost?”

Kizzy said weakly. “No’m.”

“Well, I reckon six to seb’n hundred dollars, considerin’ de prices I’se heared him say niggers costin’ nowdays, an’ you bein’ strong an’ young, lookin’ like a good breeder, too, dat’ll bring him free pickaninnies.”

With Kizzy again speechless, Miss Malizy moved closer to the door and stopped. “Fact, I wouldn’t o’ been surprised if Massa stuck you in wid one dem stud niggers some rich massas keeps on dey places an’ hires out. But it look like to me he figgerin’ on breedin’ you hisself.”

The conversation was short.

“Massa, I gwine have a baby.”

“Well, what you expectin’ me to do about it? I know you better not start playin’ sick, tryin’ to get out of workin’!”

But he did start coming to Kizzy’s cabin less often as her belly began to grow. Slaving out under the hot sun, Kizzy went through dizzy spells as well as morning sickness in the course of her painful initiation to field work. Torturous blisters on both her palms would burst, fill with fluid again, then burst again from their steady friction against the rough, heavy handle of her hoe. Chopping along, trying to keep not too far behind the experienced, short, stout, black Uncle Pompey and the wiry, light-brown-skinned Sister Sarah—both of whom she felt were still deciding what to think of her—she would strain to recall everything she had ever heard her mammy say about the having of young’uns. She felt she’d give anything if Bell could be there beside her now. Despite her humiliation at being great with child and having to face her mammy—who had warned repeatedly of the disgrace that could befall her “if’n you keeps messin’ roun’ wid dat Noah an’ winds up too close”—Kizzy knew she’d understand that it hadn’t been her fault, and she’d let her know the things she needed to know.

She could almost hear Bell’s voice telling her sadly, as she had so often, what she believed had caused the tragic deaths of both the wife and baby of Massa Waller “Po’ li’l thing was jes’ built too small to birth dat great big baby!” Was she herself built big enough? Kizzy wondered frantically. Was there any way to tell? She remembered once when she and Missy Anne had stood goggle-eyed, watching a cow deliver a calf, then their whispering that despite what grownups told them about storks bringing babies, maybe mothers had to squeeze them out through their privates in the same gruesome way.

The older women, Miss Malizy and Sister Sarah, seemed to take hardly any notice of her steadily enlarging belly—and breasts—so Kizzy decided angrily that it would be as big a waste of time to confide her fears to them as it would to Massa Lea. Certainly, he couldn’t have been less concerned as he rode around the plantation on his horse, yelling threats at anyone he felt wasn’t working fast enough.

When the baby came—in the winter of 1806—Sister Sarah served as the midwife. After what seemed an eternity of moaning, screaming, feeling as if she were ripping apart, Kizzy lay bathed in sweat, staring in wonder at the wriggling infant grinning Sister Sarah was holding up. It was a boy—but his skin seemed to be almost high yaller.

Seeing Kizzy’s alarm, Sister Sarah assured her, “New babies takes leas’ a month to darken to dey full color, honey!” But Kizzy’s apprehension deepened as she examined her baby several times every day; when a full month had passed, she knew that the child’s permanent color was going to be, at best, a pecan-colored brown.

She remembered her mammy’s proud boast, “Ain’t nothin’ but black niggers here on Massa’s place.” And she tried not to think about “sassaborro,” the name her ebony-black father—his mouth curled in scorn—used to call those with mulatto skin. She was grateful that they weren’t there to see—and share—her shame. But she knew that she’d never be able to hold her head up again even if they never saw the child, for all anyone had to do was compare her color with the baby’s to know what had happened—and with whom. She thought of Noah and felt even more ashamed. “Dis our las’ chance ‘fo’ I leaves, baby, how come you can’t?” she heard him say again. She wished desperately that she had, that this was Noah’s baby; at least it would be black.

“Gal, what’s de matter you ain’t happy, gret big ol’ fine chile like dat!” said Miss Malizy one morning, noticing how sad Kizzy looked and how awkwardly she was holding the baby, almost at her side, as if she found it hard even to look at her child. In a rush of understanding, Miss Malizy blurted, “Honey, what you lettin’ bother you ain’t no need to worry ’bout. Don’t make no difference, ’cause dese days an’ times don’t nobody care, ain’t even pay no ‘tention. It gittin’ to be near ’bout as many mulattoes as it is black niggers like us. It’s jes’ de way things is, dat’s all”—Miss Malizy’s eyes were pleading with Kizzy. “An’ you can be sho’ Massa ain’t never gwine claim de chile, not no way at all. He jes’ see a young’un he glad he ain’t had to pay for, dat he gwine stick out in de fiel’s same as you is. So de only thing for you to feel is dat big, fine baby’s your’n, honey—dat’s all it is to it!”

That way of seeing things helped Kizzy to collect herself, at least somewhat. “But what gwine happen,” she asked, “when sometime or ‘nother Missis sho’ catch sight dis chile, Miss Malizy?”

“She know he ain’t no good! I wisht I had a penny for every white woman knows dey husbands got chilluns by niggers. Main thing, I speck Missis be jealous ’cause seem like she ain’t able to have none.”

The next night, Massa Lea came to the cabin—about a month after the baby was born—he bent over the bed and held his candle close to the face of the sleeping baby. “Hmmmm. Ain’t bad-lookin’. Good-sized, too.” With his forefinger, he jiggled one of the clenched tiny fists and said, turning to Kizzy, “All right. This weekend will make enough time off. Monday you go back to the field.” “But Massa, I ought to stay to nuss ‘im!” she said foolishly.

His rage exploded in her ears. “Shut up and do as you’re told! You’re through being pampered by some fancy Virginia blue blood! Take that pickaninny with you to the field, or I’ll keep that baby and sell you out of here so quick your head swims!”

Scared silly, Kizzy burst into weeping at even the thought of being sold away from her child. “Yassuh, Massa!” she cried, cringing. Seeing her crushed submission, his anger quickly abated, but then Kizzy began to sense—with disbelief—that he had actually come intending to use her again, even now, with the baby sleeping right beside them.

“Massa, Massa, it too soon,” she pleaded tearfully. “I ain’t healed up right yet, Massa!” But when he simply ignored her, she struggled only long enough to put out the candle, after which she endured the ordeal quietly, terrified that the baby would awaken. She was relieved that he still seemed to be sleeping even when the massa spent himself, and then was clambering up, preparing to go. In the darkness, as he snapped his suspenders onto his shoulders, he said, “Well, got to call him somethin’.” Kizzy lay with her breath sucked in. After another moment, he said, “Call him George—that’s after the hardest-workin’ nigger I ever saw.” After another pause, the massa continued, as if talking to himself, “George. Yeah. Tomorrow I’ll write it in my Bible. Yeah, that’s a good name—George!” And he went on out.

Kizzy cleaned herself off and then lay back down, unsure which outrage to be most furious about. She had thought earlier of either Kunta or Kinte as an ideal name, though uncertain of what the massa’s reaction might be to their uncommon sounds. But she dared not risk igniting his temper with any objection to the name he’d chosen. She thought with a new horror of what her African pappy would think of it, knowing what importance he attached to names. Kizzy remembered how her pappy had told her that in his homeland, the naming of sons was the most important thing of all, “ ’cause de sons become dey fam’lies’ mens!”

She lay thinking of how she had never understood why her pappy had always felt so bitter against the world of white people—toubob was his word for them. She thought of Bell’s saying to her, “You’s so lucky it scare me, chile, ’cause you don’ really know what bein’ a nigger is, an’ I hopes to de good Lawd you don’ never have to fin’ out.” Well, she had found out—and there seemed no limit to the anguish whites were capable of wreaking upon black people. But the worst thing they did, Kunta had said, was to keep them ignorant of who they are, to keep them from being fully human.

“De reason yo’ pappy took holt o’ my feelin’s from de firs’,” her mammy had told her, “was he de proudest black man I ever seed!” Before she fell asleep Kizzy decided that however base her baby’s origins, however light his color, whatever name the massa forced upon him, she would never regard him as other than the grandson of an African. ~ Alex Haley.

(Roots: The Mixing of The Blood is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was first published in the October 1976 issue of Playboy. © 1976 Playboy Enterprises International, Inc. © 1993 by Ballantine Books. All Rights Reserved.)