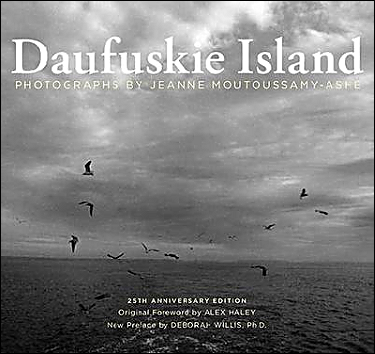

Daufuskie Island: 25th Anniversary Edition

First published in 1982, Daufuskie Island vividly captured life on a South Carolina Sea Island before the arrival of resort culture through the photographs of Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the inspiring words of Alex Haley.

Located between Hilton Head and Savannah, Daufuskie Island has since become a plush resort destination. Moutoussamy-Ashe’s photographs document what daily life was like for the last inhabitants to occupy the land prior to the onset of tourist developments.

When Moutoussamy-Ashe first came to Daufuskie in 1977, about eighty permanent African American residents lived on the island in fewer than fifty homes. Many still spoke their native Gullah dialect. They had only one store, a two-room school, a nursery, and one active church. This was all that remained of a once-thriving black society which developed after the original plantation owners left and the land was bought by freed slaves. After the boll weevil caused cotton crop failures and pollution ruined oyster beds, more and more residents sold their land to commercial developers.

It became clear that Daufuskie would soon be transformed into a coastal resort like neighboring Hilton Head, changing forever the unique island culture that survived largely unchanged for the preceding half-century.

Moustoussamy-Ashe’s photographs show family gatherings, crabbing and fishing, children at play, spiritual life, and the toils of everyday existence. With the utmost respect for her notoriously shy subjects, Moustoussamy-Ashe captured a powerful vision of their rough-hewn but rewarding life independent from many modern conveniences.

Redesigned from cover to cover, this twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Daufuskie Island includes more than fifty previously unpublished photographs from the original contact sheets, a new preface by Deborah Willis, and a new epilogue by Moutoussamy-Ashe. This hardcover anniversary edition is published to accompany a traveling exhibition sponsored by Merrill Lynch.

Foreword By Alex Haley

The voice of lovely jeanne moutoussamy-ashe pleasantly surprised me a recent morning. She had said onto my telephone recorder that across two years she’d taken pictures on Daufuskie Island, and a book of 65 or more of her selected best photographs would be published by the University of South Carolina Press. Nearly half of Daufuskie Island had been bought by developers planning another luxurious vacation resort like the adjacent Hilton Head Island, and Jeanne said, “So this book of my pictures will at least keep for the eyes of history the way Daufuskie was.” And she knew I was busy, but would I please write a foreword?

It’s a privilege. To begin, I genuinely love and respect both members of the simply meant to be union of Jeanne and husband Arthur, who, as most people know, plays tennis.

Secondly, Jeanne’s obvious absorption with the isolated, scarcely known, little South Carolina coastal island fell precisely into theme with what I’d early known to be the truly deep commitment of another close friend, a University of California (College Seven, Santa Cruz) Provost, Dr. Herman W. Blake. For years, friend Herman has practically dragged to Daufuskie everyone he could, myself included, the better to impress upon them that this represented the last survivor of the historic Sea Islands still remaining essentially as nature dictated, and that any and all possible help was urgently needed toward the objective of its preservation.

Jeanne’s asking that I write this book’s foreword advanced further in my “small world department” with the discovery that it was through two more warm friends, Donald Bogle and Verta Mae Grosvenor, that Jeanne first learned of Daufuskie Island.

Now, how all of this happened was that Jeanne and Arthur went in 1977 to Charleston, South Carolina, and renting a car they went exploring along U.S. Highway 17, which inevitably put them within the picturesque coastal country. Jeanne soon was clicking away, recording old churches, courtyards, fishermen mending nets, and other coastal types of folk, with some of whom she had struck up fascinating conversations.

Back home in New York, Jeanne was exclaiming among various friends what a great time she’d had and Donald Bogle gave her Verta Mae Grosvenor’s telephone number, telling Jeanne she’d certainly enjoy meeting the popular author of “soul food” cookbooks who was a native of Beaufort, South Carolina. That was right in the great vacation area.

Well, it didn’t take Verta Mae ten minutes before she was strongly urging the permanency of pictures should capture the final days of Daufuskie, the only remaining Sea Island which still looked as they all had as recently as fifty years ago.

Within the next few months, working around the involved logistics of accompanying much of Arthur’s heavy traveling on the international tennis circuit, Jeanne returned to South Carolina. But this time she went to the lush Hilton Head resort to meet with Emory Campbell and his wife, Emma, Verta Mae’s good friends, both of whom had grown up on Hilton Head Island when it was like Daufuskie.

The three of them came to a private development’s security guard who checked their entry credentials. Emory Campbell observed what an irony it was that in boyhood he’d roamed the length and breadth of his native island, “and now I have to pay three dollars just to visit where I used to play.” He pointed across the costly speedboats and costlier yachts moored at the Hilton Head pier. “That’s Daufuskie right over there, Jeanne.”

She saw across the water of Calibogue Sound an isolated, thickly wooded land strip with huge trees rising from the water’s edge like ageless sentinels. She heard Emory Campbell saying that crossing between the islands during his boyhood required hours in a hand-made sailing bateau, but they were now going to make that crossing in about twenty-five minutes in a hired speedboat for which he had arranged.

Within another twenty-four hours Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe had met her first few direct slave descendant natives still speaking their lilting, Gullah dialect. She had walked around in an ancient prayer house, dating back to its having been the first place of worship for the slaves on Daufuskie’s plantations. And she went next into the much newer Union Baptist Church. In a vintage White cemetery she gazed at many weathered headstones of antebellum planter families, seeing some stones’ dates as distant as 1790.

She saw a man named Johnny Hamilton urging his ox to pull his cart faster, to lessen the odds of blocking the narrow dirt road if one of the island’s few cars might approach from either direction and naturally want to pass. And Jeanne’s emotional cup about overflowed when she experienced the resigned aplomb with which Mrs. H. A. White, age 80, viewed the recent news that her island home since childhood was about to be transformed into a resort. “Well, I guess if those people buy the land, they got the right to do whatever they want to do,” Mrs. White told Jeanne. “But it’s already got to where probably every hour I see some car go by. I just know I don’t want to see it if it gets any worse.”

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe knew by then absolutely that she must schedule every possible trip to Daufuskie to photographically record these people and their island as they still were.

Maybe appropriate here are some Daufuskie vital statistics. Though it’s very near the Georgia coast actually it is within the South Carolina County of Beaufort with Hilton Head Island and Savannah, Georgia, as its closest neighbors—each of them about a forty-five-minute ride away by ferry or a twenty-five-minute ride in a speedboat. About three miles wide by nine miles long, the island faces the Atlantic, but it is bordered by both the Cooper and the New Rivers. Less than eighty-four permanent residents live in under fifty homes served by one co-op store, one two-room school, a nursery, one active church, and two active cemeteries (though six exist). The year 1952 brought electricity and, later, telephone service to the thickly wooded island, which had only dirt or sand roads, no fire department, no police, no hospital, or clinic. (Medical emergencies beyond a midwife’s ability were rushed by speedboat to neighboring Hilton Head Island.)

What seemed to qualify as Daufuskie’s oldest written records document that early White settlers massacred some Indians at a site they named “Bloody Point.” (A waterway in the general area named “Skull Creek” suggests some gory confrontation.) Later into the 1700s the island’s total of about 5,000 acres became divided into a handful of modest-sized and small plantations, their manor homes bearing traditionally opulent names such as “Melrose” and “Haig’s Point.”

No record seems to state any aggregate population figures for either Whites or slaves. But the plantations appeared to have prospered from growing the famed long-staple Sea Island cotton, bolstered by some slaves plying a bountiful off-shore area’s fishing and shell fishing. However, nearly constant tension and even fighting went on between Daufuskie’s English Tory immigrant planters and the true Whig settler-planters on neighboring Hilton Head Island.

The interisland frictions met the instant cure of the opening Civil War. Both islands were patently so vulnerable to Union gunboats that the planters and families soon left for safer Confederacy havens leaving the plantations in the care of trusted slaves. Both islands shortly were taken, as anticipated, whereupon a Union general in charge ordered the plantations surveyed into small ten and twenty acre plots to be sold only to Blacks. As the word spread, freed slaves and antebellum free Blacks rushed from the mainland to buy to the limit of their meager means.

The war ended. The Sea Islands slid back into their old quietness, with Blacks now owning most of the land. Some few White Union loyalists with pre-war Sea Island acreages were permitted to keep their holding.

During the mid-1870s with maritime trading increasing, a lighthouse was built on each end of Daufuskie. The Haig’s Point lighthouse faced the sister island of Hilton Head while the Bloody Point lighthouse looked over the open sea toward Savannah.

Gradually a post-war renewal began taking some shape. Land agents from Savannah and other mainland cities increased their convincing of individual landowning Blacks to sell their modest plots and enjoy cash money in their pockets. Sizable farms were thus patched together on which the Sea Island cotton grew lushly and the Daufuskie economy was reinforced by bountiful fishing and timber. By the 1920s the Savannah-based Hilton-Dodge Company had established a small-gauge logging train running the length of Daufuskie, carrying cut timber from logging sites for reloading at New River docks onto rafts that towboats pulled to sawmills in Savannah.

An incredible disaster then suddenly struck in the island’s cotton fields: countless boll weevils, almost beyond belief in swiftness and thoroughness, devastated entire vistas of cotton as the dreaded invader swept into the South Carolina low country.

Larger acreage White farmers, surveying the wreckage of the season’s cash crop, began selling their holdings to the visiting agents of mainland lawyers and other professional investors, and more of the small land plots filled with weevil-ruined young cotton were sold by their Black owners, many of them soon leaving Daufuskie vowing never to return.

Some other mainland investors had been giving thought to the outstanding regional reputation of the special succulence of the Daufuskie Island oysters, which were thickly harvested from the seemingly endless beds of them just off shore. Within a few months a shoreside oyster cannery was hiring workers, scores at first, finally a larger number than had ever worked in the largest fields of cotton. The oyster cannery soon shipped its specially tinned product to Savannah agents who commenced a further marketing around the world.

Some Daufuskie natives who had left began to return. The cities weren’t all that was claimed, and they had heard how the timbering and especially the oyster cannery were seeing Daufuskie thrive.

And as befitted such halcyon days, the Savannah-based steamship Clivedon began summer Saturday afternoon excursions to Daufuskie, laden with her limit of 300 passengers including a Savannah brass band. Mooring long enough to disembark all hands, the Clivedon would back out to idle in the stream while the band played for a gaiety and dancing on Daufuskie’s new wooden pavilion until finally the steamer’s foghorns would have to blast for all to reboard for a churning return to Savannah before midnight would mark the Sabbath.

Then amidst all of it the Depression struck an almost lethal blow.

The farmers struggling to replace cotton with other crops now one after another went bankrupt.

The dwindled number of Blacks who owned small plots became mostly willing to sell them now, and most cheaply, to the visiting city land agents who still had funds.

A notably unusual number of Black men died of strokes and heart attacks, a sizable percentage of them dying unusually young. And when the exodus of other Blacks to the cities quieted down, Daufuskie Island, which in 1910 had nearly 3,000 Blacks, had fewer than 300 left in 1936.

Most men and their wives not working at the oyster cannery tried whatever seemed might help them to make it through the hard times. Some commenced making weekly trips to Savannah, their little hand-made sailing bateaus laden to the waterline. Their garden produce, fresh fish, shell fish and game they sold in the city streets.

Things limped along. One or another more of the now very few land-plot owning Blacks felt they had no further choice but to sell. By 1938 at least half of Daufuskie’s total acreage was absentee-White owned.

The first rumors sounded so ludicrous in early 1939: Daufuskie’s sister island of Hilton Head might become a rich resort! Why, Hilton Head was right there, visible across the water. Many of its natives came regularly visiting back and forth, and they and everyone else knew that Hilton Head was experiencing a carbon copy of Daufuskie’s own hard times.

But then during 1940 the Daufuskie natives were utterly stunned when a Hilton Head company began actually ferrying bulldozers and dump trucks from the mainland onto Hilton Head.

World War II temporarily halted the development process, but immediately afterward it was resumed. By 1953 there was a powered ferry transporting cargos, including private cars, much faster than before. Construction of more and more private homes began, and then a Hilton Head public health center, an electric power plant, and a post office were built. Finally, in 1956 a crowded gala ceremony attended the cutting of the ribbon marking the opening of the brand new James F. Byrnes Bridge, Hilton Head’s first permanent link directly to the mainland.

Watching and hearing as all of this happened just across the waters of Calibogue Sound were the people of the sister island of Daufuskie, which was about the same as it always had been for as long as any of them living could remember.

Even then another staggering disaster hit them. State agents visiting the canning plant advised the manager that the Daufuskie oysters were officially declared “unfit for human consumption.” They explained that the Savannah River’s industrial wastes had dangerously polluted the Daufuskie offshore oyster beds. With no alternative, the canning plant was immediately closed. The scores whom it had employed wandered along the roads, sat in their homes, or gathered around the dock seeming as if they were in shock.

Now, nearly the last small land plots were sold and more natives left.

The inhabitants remaining were down to around a hundred when a White school teacher, Pat Conroy, published a book, The Water is Wide, about his experiences teaching the island’s handful of 5th through 8th graders. The book became a movie, Conrack, and that brought the despondent island some tourism—enough that during the summertime an enterprising Atlantan named C. C. “Skip” Hoagland, began a twice daily, seven days a week, ferryboat ride (plus Daufuskie land tour) which was often sold out.

A few Daufuskie folk sold trinkets or picture postcards for which the tourists loved buying stamps in the tiny ten-foot-by-ten-foot post office where Mrs. Burns served as the island’s postmistress, registrar, and notary.

Lawrence Jenkins, a tour truck driver, sold for $1.50 apiece his wife’s delicious crab cakes, as he guaranteed in a clarion tone, “No cracker crumbs, all crab meat. Four crabs in every cake.”

The tourists either arriving or leaving saw jobless Daufuskie men standing around on the dock as if they just wanted to be somewhere that something promising or helpful might happen.

The islanders petitioned for an island store. Beaufort County and government cooperative funds and agency staffs brought into being a co-op that was dedicated in December 1976. Dry and canned staples, limited meat and vegetables, and tobacco, wine and beer began to be sold by a manager and clerk, both of them Daufuskie residents.

Penn Center was established for use by the Daufuskie community and as a base for college and graduate students doing fieldwork studies of the culture and lifestyle of Sea Island residents. Soon after the filmed version of my book, Roots, was on national television, Doctor Herman Blake began urging me to join his next visit to Penn Center. I talked in there past midnight to a mixed audience of students and Daufuskie people. It seemed especially interesting how quiet, even withdrawn, the natives became after I had suggested that since they were said to be mostly of direct, even unmixed decent from their Daufuskie plantation slave forefathers, they would probably average being only eight to ten generations distant from their own original West African forefathers such as Kunta Kinte.

I reflected again upon those islanders with the next serious rumors I heard that Daufuskie investors had commissioned an architectural firm to design the next plush Sea Island resort, rumors that generated quite a considerable flurry among various facets of conservationists.

South Carolina’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism announced plans to buy all possible island acreage for the public trust as a protection against commercial development. But after a while the department said the plans were eroded by inflation and government funds cutbacks.

A S.C. Department of Archives and History scholar surveyed Daufuskie. Then formally recommended that it be placed on the National Register—protected as Beaufort County’s very last surviving undeveloped barrier island.

South Carolina’s first incumbent governor ever to visit Daufuskie, John C. West, arrived one day and was met by about thirty residents, a few summer tourists, and several Black leaders from mainland Beaufort County. Riding over the dusty roads in the little school bus, the Governor saw the islanders’ characteristic 1700s architectural gablehatch residences. He saw two (of the total six) multi-family wells and pumps built by funds from the National Demonstration Water Project. He saw Daufuskie’s other tourist sites. He then held a meeting with the island’s residents.

Governor West heard that they needed both better water and better sewerage facilities, more convenient ways of getting food stamps, and better transportation to the mainland, as well as prominently displayed “NO WAKE” signs, at both ends of the public dock, to slow down some of the Intracoastal Waterway’s high-speed traffic whose wakes damaged small boats tied up at the island dock.

But above all the Daufuskie people wanted jobs.

So many island people, they noted, plenty of their children too, were working in good regular jobs at Hilton Head which had only recently been a copy of Daufuskie.

The Governor went to the heart of the situation: its inherent ambivalence.

He said he certainly would like to see Daufuskie have not only economic but also educational advances. At the same time, practically every day his office received a new preservation pressuring. “And how does one provide residents here with economic opportunity and still keep the island in an unspoiled condition?”

To a considerable degree, even Daufuskie residents reflect the ambivalence. “I tell you, it’s like this. Some things around here need to be changed, but others don’t” was one native’s expression that mirrors their average uncertainty about whatever will happen next.

The countdown would seem to have been begun when during May of 1980 a company of development investors paid a reported 4.5 million dollars to an Aiken, South Carolina, family for nearly half of Daufuskie Island.

Nine months later in February 1981, the Beaufort County Joint Planning Commission approved a road variance for a piece of Daufuskie Island property as a weekend vacation spot.

So whatever destiny awaits Daufuskie, the last Sea Island left au naturel, appears to rest between the decisions and actions of the resort developers and the concerned Beaufort County Joint Planning Commission.

But what probably will happen seems only to reinforce how really important, even fateful, it was that Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s personal fascination with South Carolina’s coastal region led her further to Daufuskie. The emotional reaction of an artist to what she saw, heard, and felt is why you and I can now hold in our hands the quite special evidence of Jeanne’s mastery of her profession that is so repetitively attested in this book for which the University of South Carolina Press has served as the midwife.

“I think taking photographs is an experience and looking at photographs is like a journey,” Jeanne has said to me. “I’d like people to feel this book takes them to an island and its inhabitants who are living history.”

I’ve reflected on that and, you know, I believe that an island people’s history is what you’re about to feel turning pages . . . — Alex Haley

(The above foreword by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. Daufuskie Island was first published by the University of South Carolina Press in 1982. © 2007 Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. All Rights Reserved.)