Alex Haley’s Roots is the monumental two-century drama of Kunta Kinte and the six generations who came after him. By tracing back his own roots, Haley tells the story of 39 million Americans of African descent. He has rediscovered for an entire people a rich cultural heritage that ultimately speaks to all races everywhere, for the story it tells is one of the most eloquent testimonials ever written to the indomitability of the human spirit.

Alex Haley’s Roots is the monumental two-century drama of Kunta Kinte and the six generations who came after him. By tracing back his own roots, Haley tells the story of 39 million Americans of African descent. He has rediscovered for an entire people a rich cultural heritage that ultimately speaks to all races everywhere, for the story it tells is one of the most eloquent testimonials ever written to the indomitability of the human spirit.

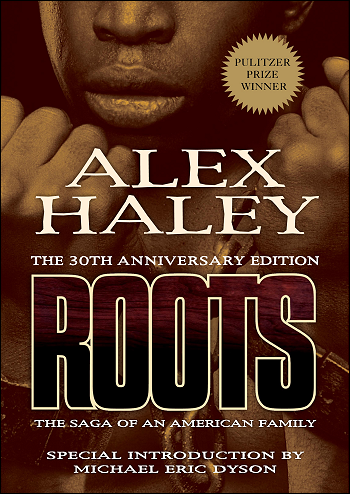

When originally published in 1976, Roots, galvanized the nation, and created an extraordinary political, racial, social and cultural dialogue that hadn’t been seen since the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The book sold over one million copies in the first year, and the miniseries was watched by an astonishing 130 million people. It also won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Roots opened up the minds of Americans of all colors and faiths to one of the darkest and most painful parts of America’s past.

Roots has lost none of its emotional power and drama, and its message for today’s and future generations is even more vital and relevant than it was thirty years ago.

Roots: The 30th Anniversary Edition was published to remind the generation that originally read it that there are issues that still need to be discussed and debated, and to introduce to a new and younger generation, a book that will help them understand, perhaps for the first time, the reality of what took place during the time of Roots.

On October 10, 1991, Alex Haley gave a speech to the employees of Reader’s Digest that included information about the writing of Roots while traveling on freight ships. This is an excerpt from that recording.

Alex Haley On The Writing of Roots

There’s something about when you go out on a ship and usually, I go out on freight ships, cargo ships; I wouldn’t get caught on a liner. How can you write with 800 people dancing? But on the freight ships, not many of them carry passengers, but those which do carry passengers carry a total of twelve, a maximum of twelve people. The law is that if a ship carries more than twelve, it must have a doctor on board. So the people who go out there tend to be very quiet people. It is said, not too far amiss, that excitement on a cargo ship is when someone finishes a jigsaw puzzle.

But what I do is I go and work my principal work hours from about 10:30 at night until daybreak. The world is yours at that point. Most of all the passengers are asleep. Sometimes there are only three other people awake on the ship. On the bridge, the officer of the day and the helmsman, and the guy who makes the rounds punching clocks every hour, and you. The thing I particularly love is when you get in there and you’ve got all your notes and your research and stuff literally in the one room with you. It’s sometimes up on your bunk, and you sleep with it all by your feet. It’s a lovely feeling—like being in the womb with what you are trying to do. I find myself from time to time, when I’m writing, I’ll do things, visual things. I’ll remember you as an audience. I’ll remember what you look like as a group. And it’s just kind of nice. And I think, well, I want to write this thing so they will read this or they’ll print that. It just comes into your head, things like that.

You’re out there by yourself. When you get far enough along, you really start to talk with your characters. I had so many conversations with Chicken George and Kunta Kinte it wasn’t even funny. It was natural. I’m sitting up in my underwear, by myself, minding my business, talking with them. And that was just as routine as it could be. Come around about 1:30 in the morning—you’ve been working since 10:30 and decide you’re going to take a little break. So you get up and you walk up on the deck. And you put your hand on the top rail, your foot on the bottom rail, and you look up. The first most striking thing is, man, you look up and there are heavenly objects as you never saw them before. You find yourself looking at planets at sea. And what you start to realize is that you never saw clear air before—even out here where it’s clear compared to New York City. This is nowhere near like it is at sea. In some latitudes, down off West Africa, South America, on the night of a full moon, there are times when you get into an illusion. If you could just stretch a little further, you feel like you could touch it. And you are out there amidst all this, God’s firmament, and then you stand and you feel through the sole of your shoe a fine vibration and you realize that’s man at work. That’s a huge diesel turbine, thirty-five feet down under the water, driving this ship like a small island through the water. Still standing there now you start hearing a slight hissing sound. You realize that’s the skin of the ship cutting through the resistance of the ocean. With all that going on, feeling these man things and seeing the God things, that’s about as close to holy as you’re going to ever get.

I find that’s why I just love to get out in the ocean. And I find that you are really out there, find yourself thinking in ways you haven’t thought before. We are here doing the jobs we all do. We really operate by rote. You don’t think. You do something you’ve done 500 times before and you know how to do it. But out there you find that your mind will engage something almost like biscuit dough. And feel it turning around and your mind can examine it and so forth. And I’ve been really seriously thinking about maybe the latter part of next year trying to see if I can’t set up a schedule where I would spend one month at sea and one month ashore right around the year. And that way I’d get my work done. And I could come back here and be all the things that you are as a kind of public writer.

As it is, it’s silly, but I would like to be cloned. I’d love to have one person who was chained to a type writer, computer, whatever. And the other one would be a public writer who would go around talking about writing. And the other would be a relatively normal human being. Something like that. It’s the truth. Most of us who are writers get writers and other creative people; I meet with a lot of creative people.

I was talking with a dear buddy of mine, Quincy Jones, two weeks ago. We were at New York for the funeral of Miles Davis. We were talking about how you get caught up in what’s called success. Once you have that blessing, it’s so hard to do what you did in the first place to get it. Quincy said he couldn’t remember when he composed anything. And I know he hasn’t; he’s so successful. Miles, bless his heart, was still playing his horn right up to the end. But lots of people who are very successful have a hard time working as well as they did before. I would tell you the truth. The best writing I ever possibly could do was when, after The Digest gave me the help to go to Africa and to go to Europe, and I was not known and I could just take my time and nobody there was pressing me. God, I don’t know how long it took me. I told all kinds of lies to editors here about when I would finish. But I was working slowly, slowly.

Let me tell you one thing more before we go. And I would like to share this ’cause we’re talking about the essence of writing now.

When I had done all the research, nine years, working in between doing articles for other magazines and stuff, I was now ready to write. I didn’t know where to go, didn’t know what to do. I knew I had a monumental task. And I got on a ship—this is where I started this freight ship thing called the Villager. And I went from Long Beach, California, completely around South America and back to Long Beach. It was ninety-one days. And I had written from the birth of Kunta Kinte through his capture. In the course of this, that’s where I got into the habit of talking to your character, I knew Kunta. I knew everything about Kunta. I knew what he was going to do. What he had done. Everything. And so I would just talk to him. And I had become so attached to him that I knew now I had to put him in the slave ship and bring him across the ocean. That was the next part of the book. And I just really couldn’t quite bring myself to write that. I was in San Francisco. I wrote about forty pages and chunked it out. You know writers know, and I know we’ve had this experience where you just know that ain’t it. That ain’t what you want to say. And when you write well, it isn’t a question so much of what you want to say, it’s a question of feel. Does it feel like you want it to feel? The feel starts coming into something around the fourth rewrite.

And then I wrote twice more about forty pages and threw it out. And I realized what my bother was. It was—I couldn’t bring myself to feel like I was up to writing about Kunta Kinte in that slave ship and me in a high-rise apartment. I had to get closer to Kunta. I had run out of my money at The Digest, lying so many times about when I’d finish, so I couldn’t ask for any more. I don’t know where I got the money from. I went to Africa. Put out the word I wanted to get a ship coming from Africa to Florida to the U.S. I just wanted to simulate crossing.

I went down to the country that was born of the U.S. People went there. What was it? Liberia. And I got a ship called, appropriately enough, the African Star. And I got on this ship. She was carrying a partial cargo of raw rubber in bails. And I got on as a passenger. I couldn’t tell the captain, who was such a nice man, nor that mate what I wanted to do because they couldn’t allow me to do it. But I found one hold that was just about a third full of cargo and there was an entryway into it with a long metal ladder down to the bottom of the hold. I’m sure most of you don’t know how big the hold of a ship is. But you could just about put this auditorium in the hold of some big ships.

Down in there they had, on the deck, a long, wide, thick piece of rough sawed timber. They called it dunnage. It’s used to store between cargo to keep it from shifting in rough seas. And what I did, after dinner the first night, I went down, made my way down into this hold. Had a little pocket light. I took off my clothing, to my underwear, and laid down on my back on this piece of dunnage. I imagined; I’m going to try to make believe I’m Kunta Kinte. I laid there and I got cold and colder. Nothing seemed to come except how ridiculous it was that I was doing this. By morning I had a terrible cold. I went back up. And the next day with my cold, the next night, I’m down doing the same thing. Well the third night when I left the dinner table, I couldn’t make myself go back down in that hold. I just felt so miserable. I don’t think I ever felt quite so badly. And instead of going down in the hold I went to the stern of the ship, the end of the ship, the back part. And I’m standing up there with my hands on the rail and looking down now where the propellers are beating up this white froth. And in the froth are little luminous, green phosphorescents. At sea you see that a lot. And I’m standing there looking at it and all of a sudden it looked like all my troubles just came on me. I owed everybody I knew. Everybody I knew looked like they were on my case. Why don’t you finish this foolish thing? You ought not be doing it in the first place—talking about writing about black genealogy.

That’s crazy. And so forth. All such stuff as that. And I was just utterly miserable, didn’t feel like I had a friend in the world. And then a thought came to me that was startling. It wasn’t frightening. It was just startling. And I make a point of saying it was not dramatic at all; it was just simply something that happened. I thought to myself, hey, there’s a cure for all this. You don’t have to go through all this mess. And what the cure was, was simply all I had to do was step through the rail and drop in the sea.

Now I say again, it wasn’t with any great dramatic thing at all; it just simply arrived at me. And once having thought it, standing there kind of musing about what I had just thought, I began to feel quite good about it. I’ve since read things—like people who were in a position about to freeze, felt warm, or something like that prior to. And I’m standing there; I guess I was half a second away from dropping into the sea. And it wouldn’t have made a difference. Fine, that would take care of it. You won’t owe anybody anything. The hell with it and all that. You can go. Hell with the publishers and the editors and all that and all this kind of thing.

And then again I stress it wasn’t dramatic; it was just sort of like everyone of us has been dreaming and you heard people speaking in a dream. And I began to hear voices, which were positioned behind me. I could hear them. They were not strident. They were just conversational. And I somehow knew every one of them. Who they were. And they were saying things like, no, don’t do that. No, you’re doing the best you can. You just keep going. You go ahead. And so forth. It was like that.

And I knew exactly who they were. They were Grandma. They were Chicken George. They were Kunta Kinte. They were my cousin, Georgia, who lived in Kansas City and had passed away. They were all these people whom I had been writing about. They were talking to me. It was like a dream.

I remember fighting myself loose from that rail, turning around and I went scuttling like a crab up over the hatch. And finally made my way back to my little stateroom and pitched down, head first, face first, belly first on the bunk and I cried dry. I cried more I guess than I’ve cried since I was four years old, at least it seemed so.

And it was about midnight when I kind of got myself together. I can’t really describe how it felt, but it was like recovering from a vacuum or something. Then I got up and the feeling was—you have been assessed and you’ve been tried and you’ve been approved by all them who went before. So go ahead. And then I went back down in the hold. I had a terrible cold, head cold, flu-ish like. I had with me a long, yellow tablet and some pencils. This time I did not take my clothing off like I’d been doing before. I kept them on because I was having such a bad cold. I laid down on the piece of timber. I had the tablet there, when I would think.

Now Kunta Kinte was lying in this position on a shelf in the ship, the Lord Ligonier. She had left the Gambia River July 5, 1767. She sailed two months, three weeks, two days. Destination: Annapolis, Maryland. And he was lying there. And others were in there with him whom he knew. And what would he think?

What would be some of the things they would say? And when they would come to me in the dark, I would write. You know how you can write kind of large looping letters on something.

And that was how I did every night, only eight nights. From there, to this country, to Florida and when I got to Florida, I remember rushing through the big, big Miami Airport. I came in at 1 am and I had to go to the other end. Barely made the flight. Flew back to San Francisco. Got with a doctor, Kimbro was his name. And he kind of patched me up and gave me stuff and everything, antibiotics and all until I got ready.

And then I sat down with those long, yellow tablets and transcribed and then I began to write that part which is now in Roots as the chapter where Kunta Kinte crossed the ocean in a slave ship. And that was probably the most emotional experience I had in the whole thing. Again it all really goes back to here, Reader’s Digest, the morning the editors met at the place up there and said they believed in it and they would sponsor me. So, thank you. ~ Alex Haley.

(Alex Haley On The Writing of Roots is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. © 1991 The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. © 2007 by Perseus Books Group. All Rights Reserved.)