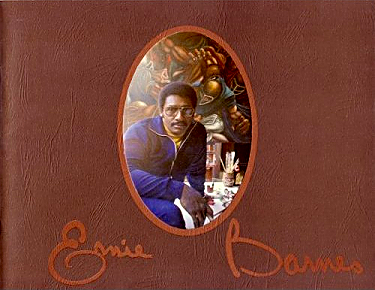

Ernie Barnes (1938 – 2009) was one of the most popular artists in the world. His depiction of the African American experience is unique and his vivid imagination is reflected in his artwork.

Ernie Barnes (1938 – 2009) was one of the most popular artists in the world. His depiction of the African American experience is unique and his vivid imagination is reflected in his artwork.

Ernie began painting while playing college football at a segregated North Carolina College. He went on to play in the NFL, starting his career with the San Diego Chargers in 1960. Barnes then decided to call it quits and paint full-time. Many people recognize his painting called “Sugar Shack”—a jubilant dancing scene that appeared on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s album “I Want You” and was shown during the closing credits of the TV sitcom Good Times.

Most of Ernie’s artwork reflect his view of African American lifestyles, but he also shows us his continued love for sports. He also has a commitment towards racial and ethnic harmony and many of his paintings reflect it.

With all things considered it’s easy to see why Ernie is one of the most collected artists in the world.

For the 1984 summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Mr. Barnes created five official posters. Over the years he completed commissions for clients like the NBA, Seton Hall University, Sylvester Stallone and Kanye West. His work has been purchased by celebrity collectors including Charlton Heston, Mary Tyler Moore, Alex Haley, Burt Reynolds and Dr. Jerry Buss, the owner of the Los Angeles Lakers.

Alex Haley contributed to Ernie Barnes / Artist by writing the following essay:

Ernie and I will forever treasure how a mutual friend, an influential patron of the arts, discovered that we knew of each other, but had never actually met, and soon arranged a formal soiree jointly to honor and to introduce the eminent artist and the eminent writer. High up in a metropolitan penthouse, the lushness and the guest list made the event practically a state occasion and the evening was halfway over before Ernie and I got a chance to exchange with each other any more than a “How do you do?” Inside of two minutes, I’d guess, to our mutual delight, we found ourselves sharing our Southern boyhoods and that we had done about precisely the same things although living in respective distant hometowns. I remember my own startled surprise when we recalled even the same initial efforts at art: On spring or summer days, when very light showers would have dampened the earth, we’d happily rush outside, gulping the rain-freshened air, racing along, glancing back over our shoulders at the clear trail of tracks our footprints were leaving. Finally tiring of that, we’d stop somewhere and using either a stick or a forefinger in the rain-softened earth, we would make line drawings of whatever came to our minds.

Ernie has since said that not only was nothing unusual in our duplicate experience—with him in Durham, North Carolina, and me in Henning, Tennessee—but that, universally, all children’s drawings graphically manifest the degree to which all of mankind is as one. He says, “A boy of Africa’s Boki tribe may make a mask with the same markings that are the drawings on a wall of a little boy in Los Angeles, or a tree drawn by a young girl of Milano, Italy, may look like a tree drawn by a young girl in West Virginia. The artistic impulse is the natural language of aesthetics, among all the people of the earth.”

There was, however, something very special about Ernie’s boyhood drawings—for they presaged a gifted adult major artist. In fact, I feel that a dramatic feature motion picture, or a television series, could be made of how, finally, that gifted major artist emerged. Biographically, Ernest Eugene Barnes, Jr. was born in Durham on July 15, 1938. (That makes him a Cancer for the astrology buffs.) Four years later, a younger brother was born, named James Wesley. Their parents were Fannie and Ernest E. Barnes, Sr., who worked as a shipping clerk at the local tobacco factory. Toward his pair of sons, Ernest Sr. was distant and stern, but at unpredictable times they would find him tender. The bulk of his sons’ rearing needs, Ernest Sr. entrusted to his wife’s decisions. He often said, “Fannie knows what to do for those boys.”

Mrs. Barnes worked as a housemaid. Her love and her concern for her sons was demonstrated to them each day of their lives. For them, her husband and herself, she created a home that was luxuriant in the human spirit. Every morning witnessed the Barnes family knelt in prayer before anyone left for work or for school. Proper table manners during the meals were enforced most strictly. The two boys knew their homework had better get completed before their 8 o’clock bedtime. They knew that the Golden Rule of “Do unto all others” was their unwavering rule to live by.

And Mrs. Barnes brought home more than items of food from her employer’s kitchen. She also brought their discarded classical record albums and art prints, which cultivated her boys’ nascent cultural impulses. The two Barnes lads were familiar with such names as Brahms, Liszt, Haydn, Debussy and Beethoven long before they registered in the first grade.

The Barnes family’s twelve-room, imitation-brick home stood in great contrast to the weathered gray other dwellings along Willard Street. It was an unpaved street in a black community whose people were caught in a net of want. It was a street among whose residents where fewer wanted to accomplish something in life than those who felt that life owed them some accomplishment. “Outsiders,” alien to the culture of such black communities, may have been disdainful of Willard Street, but young Ernest was among those who loved it, and its people whose activities were the subjects of some of his earliest “serious” penciled drawings. He drew the drunks, he drew the junk man, he drew the people en route to work, or to church and whatever else caught his eye.

But many of Willard Street’s other youngsters didn’t like Ernest; they regarded him as a misfit. Physically, no Willard Street boy was bigger than he was, but he evidenced no interest whatsoever in athletics. He didn’t even cuss like the other boys; they loved to taunt him and pick fights; he got beaten up so repeatedly until, as a crowing insult among his peers, the teachers let him leave school to head home 15 minutes ahead of the regularly scheduled time. When Ernest found that pornographic images would amuse his peers, he began using his drawing skills in that direction, as an avenue to enjoying at least some peace. Neither he, the other boys nor the school teachers would have dreamed that notwithstanding the subject matter, the constant act of drawing was developing Ernest’s technical skills.

His general sense of self-esteem was quite low by the time he reached the seventh grade. It gave him pleasure that now or then teachers spoke of him as “a fine little artist,” but that afforded him little comfort in his peer relationships. No day would pass without some embarrassing reminder that he lacked the toughness or the roughness which gave such popularity to those who were athletic—especially to any who were as big as he was. Almost everyone seemed to equate manhood itself with success in sports.

Finally, the jibes, the jokes and the jeers began to embarrass big, gentle, peace-loving Ernest Barnes before the girls he liked. Angrily, he gritted his teeth and determined that he was going to make himself play football. And it took a painful physical and psychic crucible of transition: intensive weight-lifting, grueling gymnastic exercising, mind-analysis, imitation of others, personal trial-and-error. And eventually it was an Ernest Barnes with a body like a steel spring who graduated from his high school as its biggest football hero—with 26 full athletic scholarships to choose among. He selected North Carolina College (now NC Central University) to major in art. And nobody laughed anymore.

It was at NCCU that Ernest met Ed Wilson, the Chairman of the Art Department, who today Ernest credits for his development as an artist. Perennially, Wilson had voiced his dissatisfaction with the average freshman art major aspirants. Some had won prizes in hometown poster contests. Others had spent their high school days cutting designs from construction paper. Wilson said that hardly anyone else ever showed an awareness of what he termed “eye-mind linkage.” Pitiably few had paid any attention to actual life experiences, he said, and his students heard him assail what he called “visual illiterates.” But where Wilson sensed a talent, he nurtured and encouraged it. He declared that one’s native gifts never should get smothered under the mechanics of learning art techniques. He said that he designed his courses to lead gracefully in an individual approach to art. From Wilson’s teachings, gradually Ernest learned that first an artist should experience before painting. To his great surprise he found a parallel between art and football—that inherent within the clash, the pounding, the striving and driving, there was an almost divine accord of beauty and grace. He discovered that both football and art were exacting endeavors where the performer was lauded for his grace of form against opposing forces. The human body was rendered beautiful when imbued by the spirit of greatness, he discovered, and art is great as it translates and embodies this spirit.

After college in 1960, Ernie Barnes became the tenth-round draft selection of the World Champion Baltimore Colts. Over the next six years, he played offensive guard, first with the San Diego Chargers, then with the Denver Broncos. During this period, he never let his love of football overshadow his love of art. The football gave him the enormous satisfaction of achievement, of being able to do something extremely difficult, and do it well. The art allowed him the privilege to interpret for the public his concepts of the relationships between art and life.

In 1966 Ernie Barnes retired from football to a total devotion to his art. It is by now redundant to say that Ernie Barnes has more than established himself as one among America’s leading contemporary painters.” ~ Alex Haley, 1979.

(The above Alex Haley essay is presented under the Creative Commons License. © 1979 Ernie Barnes Family Trust. All Rights Reserved.)