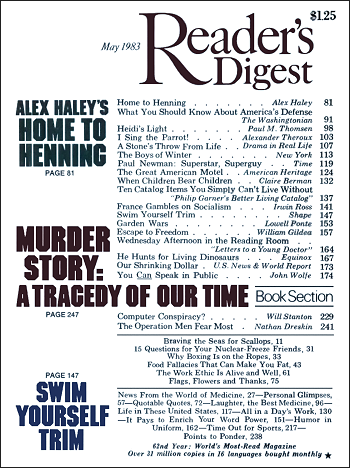

(Home To Henning by Alex Haley was originally published in the May 1983 issue of Reader’s Digest.)

(Home To Henning by Alex Haley was originally published in the May 1983 issue of Reader’s Digest.)

Alex Haley grew up in Henning, the West Tennessee hamlet that provides the title for his forthcoming memoir. Haley’s first book was his Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965); his second book Roots not only became a household name but gave crucial impetus to the nation-wide movement to recover and preserve family history.

In his interview, Alex Haley: Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1989: Angels, Legends, and Grace, with William R. Ferris (Professor of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Alex Haley mentions the following regarding the South and the hands of old ladies: “I innately love the South. I really, truly think it’s the best place in this country to live. I like the people. The people are kinder, certainly better raised than most of the people I’ve met from other parts of the country. We are. And it’s not generally mechanized, industrialized, technological—people’s hands are doing things.

“If you look at the hands of old ladies, they’ll tell you more about their life than a little bit. It’s said that women’s hands, in particular, show their age and what their life has been like more than anything else about them. And I just feel the South is a place of hands, it’s a place of touch, of caress, of less slapping and knocking people down. It’s a softer, sweeter culture, on the whole.

“I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else but in the South. I love how you go around here and people know how to say ‘yes, sir’ and ‘no, ma’am,’ and people know how to speak, to be kind, and to smile. It’s not that way in other parts of the country. They’re fine to visit. But this is home.” ~ Alex Haley.

Home To Henning

Pete Gause had been one more among Henning’s annual young black men who decided that graduating from grammar school was enough of education, and then he went and hired himself out as a fieldworker. He chopped, plowed and picked cotton until he had saved up $9.65, with which he went downtown to the train depot where he bought, in advance, a one-way, coach-class ticket to Chicago on the Illinois Central. Then Pete kept right on farming for 5½ days every week, and even took other weekend jobs. Finally he had saved $50, which some Henning people living in Chicago, who were back home visiting, had assured him was enough to see him eat and sleep long enough to find himself a job that would put him on his feet. And so one Sunday afternoon, Pete Gause, 18, filled with his dreams, caught himself a train, like many another before him, to get Up North and do good.

As was always the case when anyone went Up North, the community expectantly waited to share the first report back to relatives. But quite a number of weeks went by and Pete’s mama, good church Sister Fannie Gause, was only able to tell her closest friends that she had heard from her boy nary one word as yet. Her friends relayed this all along The Lane, where most of Henning’s black people lived, and added that they could tell that she was worrying about her Pete pretty hard.

Then one day Sister Fannie went happily popping by to visit just about everybody. She let them read for themselves Pete’s hand-printed letter saying he’d found a restaurant dishwashing job, and the beaming Sister Fannie also showed the five-dollar bill that Pete had enclosed for his mama. Up and down The Lane after she’d left, the people commented how nice that was, especially considering how plenty of others, Up North long in later discussions they could declare he never got out of their sight. He passed right through town and finally stepped onto the wide dirt Lane. Making a right turn, he saw Sister Fannie just as she also saw him—and came running with her arms stretched wide, her apron flapping, and she was crying. Everybody else who Juniebug had found at home along that part of The Lane was watching them hug each other, before they went on into Sister Fannie’s little old gray-planked, rundown, four-roomed house.

Sister Fannie later on told her close friends what happened inside, and they told everybody else. She said that from the second the door shut, for them both it felt so awkward. She was beyond being happy to see her boy again, of course, but she just didn’t know what to say, or do. There was such a difference between the Pete she’d last seen and the man she stood looking at, holding his homburg in one hand as his other set down his fine black-leather bag against a worn-through in her linoleum floor. She reached and took the hat and said, “Let me rest your coat.”

She stepped into the bedroom and put the coat on a wire hanger and hung it on the nail behind the door. Coming back out of the bedroom, she told Pete that would be his room. And then she said she couldn’t believe her ears, hearing him tell her he really was sorry, but he was going to have to catch that afternoon’s five-o’clock local to get back to Chicago in time for his regular Seminole job the next morning.

Sister Fannie said her knees and legs, both, suddenly felt weak. She could accept how busy he was and all, but it was just not having seen him for all that long, plus all of her friends whom she’d faithfully promised at least a chance to say hello to him. She said she collected her wits somehow and gestured him to a chair, and they both sat down. Pete asked how was she, and everybody? “All right,” she said she told him, so confused and heartsick about him leaving that same day, that then in sudden embarrassment she realized she hadn’t even asked about his wife. Then she did, and all he said was “Fine.”

There had to be something they could talk about, Sister Fannie said she thought. And she just started making her head give her some names of people there in Henning whom Pete couldn’t help but remember, and telling him such things as that they’d married, and how many children they had by now, and especially among the older people, how some had suffered sicknessess and most had gotten well, but a few had died. And Pete, sitting there, listened.

Sister Fannie said then she talked some about how hard the Depression had hit both black and white, had hit just everybody, and how the money Pete had sent had helped her out a lot, every time.

She was thinking about what to say next when, Sister Fannie said, somehow it popped into her mind to ask, “Son, maybe you’d care for a cup of coffee or tea?” And Pete even smiled a little when he nodded and said, “Yes ma’am, I’d love some tea.”

Sister Fannie practically jumped up, having something she could do with herself, and she stepped through her doorway’s bleached flour-sack curtains hanging from a wire tacked across the door frame between her living room and her kitchen. Pushing a few fatty pine kindling sticks over the old embers from her breakfast-cooking fire, she reached up after her dried green tea leaves in her cupboard. Then, she said, she kind of half-turned about, sensing that her Pete must have entered through the curtains.

She said that she hadn’t realized what a really big man Pete was, that he filled the door frame entirely. And right then she noticed how strangely Pete was looking down upon her old cast-iron black cook-stove. She first hoped that maybe he was remembering that stove’s thousands of breakfasts, dinners, and suppers eaten by him and his brothers. And then she felt embarrassed that her stove looked so bad, its slightly parted oven door hanging by one hinge, its missing right front leg substituted by some thickish hickory firewood sticks, and the baling wire she had nailed onto the ceiling looped down and around the rusting stovepipes to stop them from sagging further.

Sister Fannie said she saw such a frightening expression suddenly come over Pete’s face that her own mouth just popped open to ask, “Is something the matter?”

Pete took one step and there he was half-crouched before that stove; suddenly his long-sleeved arms and thick hands were gripping the stove’s underside.

Sister Fannie said she just jumped backward, her hands flying to her mouth, her eyes popping, as Pete with a great grunt wrenched up that whole heavy cast-iron stove from that floor, the kindling crackling inside, and her water kettle, breakfast-eggs skillet and tin biscuit pan all tumbling and clattering against the floor. With another two wrenchings, to the left, then to the right, like he used to wrestle cotton bales, Pete tore that cookstove’s top loose from the overhead stovepipes.

She said with the stove held waist-high and a little stream of ashes sifting down from the firebox, Pete turned toward her kitchen’s back door. Then, maneuvering that iron stove through that doorway, with another mighty grunt Pete just heaved it forward and outward, and it smashed down against her little grassy-patched dirt back yard, the sounds of the crash and the iron cracking open sending her little spotted feist dog and her few any-breed chickens all yelping and squawking and flying.

Pete’s face was dripping sweat, said Sister Fannie, as he said between loud, hard breaths, “Be right back.” And with long, dignified steps, he headed back downtown. There in the Henning Hardware and Supply Company, which was owned by Mr. Jim Alston, the combined janitor-deliveryman was Spunk Johnson. How Spunk later told it along The Lane was that he was back in the store’s rear, sort of shoving around some empty wooden boxes, for even without any business going on, Mr. Alston would get unhappy unless he could hear some noises sounding like Spunk was doing some kind of work. Spunk said that he liked being back in there because he could also hear everything that went on up front.

Spunk said that suddenly Mr. Alston’s voice was strangely high-pitched, asking somebody, “What can I do for you?” Spunk said he quit shoving boxes, listening sharply to find out who it was that made Mr. Alston sound so uncertain. Then hearing, “I’m interested in a cookstove,” Spunk said he nearly fell over, recognizing that the black man speaking so dignified could be nobody else but Pete Gause.

Spunk said he quickly moved between some tall cardboard cartons to where he could peep around them safely, and there sure enough stood Pete Gause.

Spunk said Mr. Jim Alston, pointing to a display model, spoke next in the same strained tone. “Your people buy that one. Fifteen dollars and ninety-five cents.”

Then Spunk heard Pete Gause. “Which is the best stove you’ve got?”

Mr. Alston hesitated. “Well, this one. See, this side tank here keeps five gallons of water hot. And that thermometer right there measures what heat’s in that oven. And this warming oven, up top here.”

“How much? Cash.” Spunk heard Pete Gause ask it, and he saw Mr. Alston react as if he didn’t believe it. Even the richest of Henning’s white folks wanting anything real big like that would very seldom pay full cash on the spot.

“Sixty dollars. Fifty-eight cash,” Mr. Alston said.

Spunk Johnson said it was the first time his eyes ever beheld any black man just sliding his right hand into his pocket and drawing out his wallet and counting six green ten-dollar bills into Mr. Jim Alston’s hand.

Spunk said Mr. Alston’s face had begun turning that excited white folks’ bright-pinkish color. And then Pete Gause said, “Can it be delivered to my mother’s home, up on The Lane, right away?”

“Sure can, right away!” And Mr. Alston hollered, “Spunk!”

Spunk said he acted like he had no idea what was going on.

Mr. Alston pointed. “I want this man’s stove delivered to his house, right now!”

“Yessir,” said Spunk, and then he said he realized he was looking right at the Pete Gause he grew up with. So Spunk said, “Glad to see you back. Hear tell you workin’ with the railroad up yonder roun’ Chicago.”

Pete Gause said, “Yes, I am, and I appreciate you taking this stove up to my mama.”

Spunk said it sounded so weird considering how he and Pete went to Henning’s Colored Grammar School together, so he tried again, being homefolksy. “Why, shore. Sister Fannie maybe’s tol’ you, ain’t many weeks pass either Lucy Mae or me or both us don’t jes’ drop by an’ say hi’dy—you know, jes’ see how she doin’.”

“I appreciate that, and know mama does, too,” said Pete Gause. “If you set up her stove for her, I’d be glad to pay whatever you’d charge.”

“Oh, ain’t nothin’, be glad to,” said Spunk.

Then Spunk said he went on out to hitch up the store’s big bay mare to pull the open-bed delivery wagon. Within only a little over an hour, he had set up Sister Fannie’s brand-new, fine cookstove, all ready for starting a fire in it and cooking somebody a good supper.

But, instead, about when Sister Fannie would have been cooking a supper, as she would so much have loved to be doing for Pete on the stove he’d bought that she felt was too beautiful and wonderful to describe, she was down at the Henning I. C. railroad depot, keeping up her best efforts to hide her crying from Pete, as she had been trying to hide ever since he had told her he was leaving so soon.

Since Pete’s arrival that morning, enough word had circulated that although by far most people were out working in the fields, still a good number, especially older people, had gathered in front of the stores across the highway from the depot. They wanted at least a peep, if nothing else, just to be able later to say they had really seen Pete Gause who, after 15 years, came home and then left the same day. The black people stood out in the open along the sidewalk, while the white people mostly looked out from behind different stores’ windowpanes or closed screened doors, so nobody could say that they had showed enough concern to go outside.

At about 4:45 p.m., the I. C. local’s first whistling was heard, and the people watching from downtown across the highway saw Pete Gause turn quickly and tightly hug Sister Fannie, who they could tell clear across the highway was now out-and-out crying. Lifting his real-leather bag, Pete walked onto the coach for black passengers. Everyone watching now strained their eyes, scanning the windows of the coach. That was because practically all black people, once on board, would rush to the nearest of the windows facing town, leaning over passengers already seated, if necessary, and just wave and wave through the window’s double-paned plate glass at the homefolks they were leaving. But Pete Gause never showed up at all. He must have lust taken a seat on the opposite side and stayed there.

The big locomotive whistled two little toots, its deep chuff-chuff-chuffing began moving the train ahead, and gradually it gathered speed, heading out of town. Around that Friday’s sundown, the news spread so fast among the arriving fieldworkers that by night the whole town’s talk was of nothing but Pete Gause. By breakfasttime on Saturday morning, members of the Ladies’ Aid Society who were living closest went to offer a morning prayer with Sister Fannie for the Lord’s goodness just to have let her raise such a child. Of course afterward she showed them her new cookstove, which later some folk said had been their real purpose in the first place.

Then, as usual for a Saturday morning, downtown Henning began growing busier and busier as more and more wagons and buggies kept entering the town square. They were all filled with outlying country folk, who looked forward all through every week to spending Saturdays among the big crowds in town. And it was a peculiar thing that most people, town or country alike, after they had heard what had happened, showed no interest at all in Sister Fannie’s new stove. Instead, starting around that Saturday’s noontime, then increasing steadily during the afternoon, usually by twos and threes, both town and country people quietly began walking away from the crowded, busy downtown. They would keep on going until they’d reach and turn right into The Lane.

The people would sort of cater-corner in an angling toward Sister Fannie’s small, partly grassed front yard decorated with big cantaloupe-size, white-painted rocks arranged in a circle around her two worn-out tin washtubs of dirt holding her flowering plants. And then passing her small, oblong house, the people would reach her back yard and see the broken old stove there, as they had heard.

The people generally wouldn’t walk very close to the old cookstove—they’d stand a few yards back, as if to get a fuller look. It lay all crunched down on one side, even seeming to be dug-in a little into the disturbed hard surface of the yard. A gaping split about four or five inches wide had nearly left the stove in two halves.

After a while, some of the people would abruptly say something, almost to themselves, as one man marveled softly, “He sho’ throwed it!” and the people close to him nodded. Other people seemed unable to believe buying anything so costly without a saved-up down payment, then fifty cents a month forever, which made another man kind of breathe, “He come at ‘leven, he lef’ at five—Lord have mercy!”

Somewhere between 200 and 300 people must have come and looked at Sister Fannie’s old cookstove within the next few weeks. Different Henning people, in discussions, agreed what a beautiful thing it was that a hometown man had come back and done that for his mama. And it was the first time, it was further agreed, that anybody off The Lane ever was able to go downtown and order the very best of something costing really big money, and then peel off green bills until the white storeman didn’t even know how to act.

For years to come, in fact, black people kept on walking up to see Sister Fannie’s broken old stove. And the reason was that just looking at it gave the black people of Henning a mighty big feeling of pride.

(Home To Henning by Alex Haley is presented to our audience under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the May 1983 issue of Reader’s Digest. © 1983 The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)