When Maya Angelou writes, she rents a room in a hotel where none of the staff will admit knowing who she is.

When Maya Angelou writes, she rents a room in a hotel where none of the staff will admit knowing who she is.

Whenever Pat Conroy needs jump-starting, he phones his friend Doug Marlette, hoping to catch him on a mean day: “When Doug is vicious, it’s poetry.”

At times when the words wouldn’t come, Alex Haley used to mix cake batter, pop it in the oven and pull up a chair to watch “that absolutely miraculous process of something being created from raw material.”

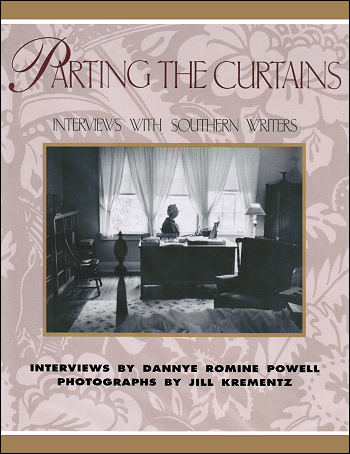

The twenty-three Southern writers perceptively interviewed here by Dannye Romine Powell are as varied in their approaches to writing, their habits, and their opinions as they are in the kinds of art they produce. But though they are as distant in years as Kaye Gibbons and Eudora Welty, and as different in background as Dori Sanders and Walker Percy, each “braves his or her way onto the blank page day after day, trusting the subconscious, believing in the power of language to lift us out of ourselves,” as Powell says.

Whether their triumphs involve getting inside the skin of a Confederate widow, like Allan Gurganus, or completing some of their best work after suffering personal tragedy, like Reynolds Price, all these writers share the goal stated by William Styron: “To finish a work of literature that fulfills every shred of my talent.”

Introduction To Her Alex Haley Interview By Dannye Romine Powell

When Alex Haley enters the Atlanta TV studio, his name is not yet a household word. It will be in another week, when Roots: The Saga of an American Family vaults to number two on the bestseller list.

Haley, born in Ithaca, New York, and raised in Henning, Tennessee, moves into the WSB-TV studio as unassuming and silent as a shadow. But under the bright lights, his energy begins to uncoil. He talks about how he picked through the slim clues that led him from this country, back across that ocean “which every one of us here in America crossed,” and into deepest Africa.

It was in Gambia, on the outskirts of a village, that Haley heard from the chief Griot—a man whose meticulous memory is trained to span generations of oral history—the same story he had heard since childhood: The story of his four-times great-grandfather, Kunta Kinte, who went out of the village to chop wood one day in 1767 and was never heard from again.

“In that miraculous moment of discovery,” he says, “I was really rendered almost mute and dumb. There are just no words to convey that emotion.”

Now, Haley transformed from researcher into evangelist.

“Go with all possible haste to the oldest people in your families,” he urges the TV audience. “They may be holding in their heads some of your most precious gifts. They may be holding in their heads the clues to your own roots.”

“And family reunions. We have got to start in this country a return to family reunions. There’s a magic moment when the chairs are lined up and the oldest members of the family are sitting in the softest, easiest chairs holding those wriggling babies, and all the middle-sized people are standing up. And the camera goes click, and everybody who was there walks a little taller because they were there and they know the beat of their family, and they know who they are.”

Haley’s schedule is jammed, The only time he can sit for an interview is at five o’clock in the morning in the Atlanta Hilton Hotel. Here, night easing into day, Alex Haley talks about learning to write, about cranking microfilm to find his ancestors, and about his love for his own roots, lovingly nurtured in the little town of Henning, Tennessee. ~ Dannye Romine Powell

Alex Haley Interviewed By Dannye Romine Powell

(October 1 and 2, 1976)

Powell: During your 20-year tenure in the Coast Guard, you rose from cook—with a time-consuming hobby of writing love letters for your shipmates to their girlfriends—to the official position of chief journalist. What did you learn during those years about the difference between writing letters and writing articles and books?

Haley: One night, there was a book around that I’d read pieces of off and on. And I just picked up that book and propped it on the typewriter, and I began with just the pure, capricious intent to type a chapter of this book onto this piece of paper.

Well, I started, and I tell you what happened. Around the second paragraph. I began to feel, for the first time in my life, what good writing felt like in a typewriter. It was disciplined, it was sharp with clarity, every word was necessary, the sentence structure was beautiful.

That thing grabbed me. It just simply did. I wanted to somehow make my writing feel like that. And I set out in that direction.

Powell: You’ve said that when you’d get stumped writing, you’d go in the ship’s kitchen and mix up a cake and pull up a stool to the windowed oven and sit there with your head in your hands watching that thing bubble and seethe. In fact, you’ve compared that process of the cake baking to the process of writing.

Haley: I would look at that cake batter in the pan, and it would look as if it would ever be thus. Then, miracle of miracles, a bubble makes its appearance in some unexpected place. In another second, another bubble makes its appearance in another location. And another will do the same. And then, you know, what you start watching is that absolutely miraculous process of something being created from raw material. And what is being created is really quite different from the raw material. And that is a very similar thing to the process of writing. You have your notes and your memories and your feelings, and those are your ingredients. But that thing that happens in your hands and in your head—when you do it well—creates another thing entirely.

Powell: When yon got out of the Coast Guard in 1959, you decided to pursue writing as a career. You headed straight for Greenwich Village, rented yourself a basement apartment, and, as you’ve said, “prepared to starve.”

Haley: One time, I was down to eighteen cents: A nickel, a dime, and three pennies. In my little cupboard I had exactly two cans of sardines. And I just did something crazy and capricious and dumped them all in a little box.

Well, I carried the little box around with me for years, and it wasn’t until much later that I had enough money to have the two cans and the eighteen cents framed. I have them right over my mantel today in California, and they symbolize for me the “hanging in there” when I didn’t know I could make it.

Powell: Your writing was selling regularly. but you wanted to hit bigger markets.

Haley: I wanted desperately to write for Playboy. I was given an assignment by them to do an interview with Miles Davis, but he wouldn’t answer my questions with anything but a yes or a no. So I wrote an expository lead and put the rest into question-and-answer format, and Playboy liked it so much they decided to continue that format. You might say that the Playboy interviews evolved by accident.

Powell: You interviewed Malcolm X for Playboy, which led to your coauthoring The Autobiography of Malcolm X. That book earned you your first real writing money and some leisure. What did you do next?

Haley: I was kind of in a vacuum period after the book was finished, and the time was in the sixties, and there was a lot of talk then about blacks and about Africa. And I had all these stories in my head that my grandma and her sisters had always told me. About how they were born in Alamance County in North Carolina on Master Tom Murray’s plantation. They just talked about it repetitively until those stories were like Biblical parables I learned in Sunday school. I just sort of knew the name Alamance County like I knew the name Bethlehem.

Powell: And then there was that day in 1965—before the world had ever heard of your four-times great-grandfather Kunta Kinte of Gambia, Africa—when you went to the National Archives in Washington and asked to see the 1870 census records for Alamance County. They brought you eight rolls of film, and you turned that crank, watching the names “march in stately tread” until you got to the fourth roll. Then there came that moment that galvanized you, that stopped you cold.

Haley: I saw Tom Murray, blacksmith, wife’s name Arrena, and listed below were the names of my aunts. There was Aunt Vinnie. And there, for God’s sake, was Aunt Liz. The Aunt Liz who sat on the porch with long gray hair, and these census records showed my Aunt Liz was only six [in 1870].

I came out of there bewildered. The more I kept thinking about it, the more my mind kept going back to childhood, where I had first heard the story of “the African” who had been chopping wood when he was kidnapped.

Powell: Your emotions must’ve been a choppy sea that day.

Haley: There were times when I felt like walking back through history swinging an ax. I began to find some thing in me, some fury. But fury is something that at best can immobilize and at worst can destroy you.

People have asked me if delving into the past like this is going to stir up trouble again for blacks and whites. I say, “Hell, no!” We’ve spent so long cosmetizing and hiding. Let’s get it out there and look at it and deal with the legacy.

Most white folks don’t know much more than black folks about where they came from. Black folks all think white folks can trace their families back to William the Conqueror. I hope we’ve transcended that feeling. I want to be evangelistic about this particular thing. I want to spread this concept, this awareness of a sense of our own roots, throughout the country.

Powell: You worked on Roots for ten years, often returning to the sea for extended writing stints. Why the sea?

Haley: After about three days in a ship’s stateroom, you feel like you’re in a womb, and you can just write like crazy.

Powell: You’ve had two failed marriage. Maybe your obsession with writing doesn’t mix well with domesticity.

Haley: It was my life to learn to write, and that just didn’t make me very domestic. I just simply was married to what I was doing, and I freely admit it. In some kind of way, I don’t feel a whole lot of guilt about it. I just couldn’t help it.

Powell: You’re writing a book now about how you discovered your roots—the book behind the book. Then what?

Haley: I want to write a book about that dusty, sleepy little town of Henning, Tennessee. It is said, and properly said, that anytime a small town in America dies, a little bit of America dies with it.

And Henning is symbolic of every small town in America. Every emotion a human being can feel is evoked in it. I feel I have that book like a lollipop in my mind.

It’s very meaningful to me that I just sort of came out of Henning, and I’ve seemed to retain its values. It’s like although I now live and operate within a big-city context, deep down inside, I’m still small-town, and I’m not too sure about all of the city slickers, really.

(The above interview of Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. Parting The Curtains: Interviews With Southern Writers is written by Dannye Romine Powell. © 1994 John F. Blair, Publisher. All Rights Reserved.)