When Jimmy Carter was elected President in 1976, pundits hailed the advent of a “New South” and proclaimed an end to a century of separation.

When Jimmy Carter was elected President in 1976, pundits hailed the advent of a “New South” and proclaimed an end to a century of separation.

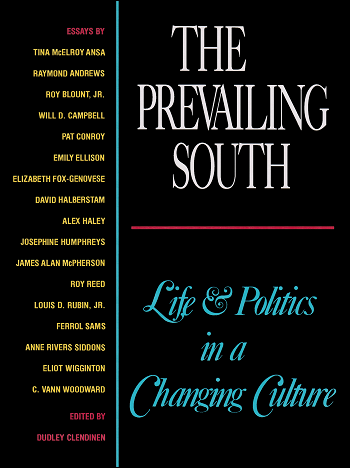

Twelve years later, both the Democrats and the Republicans went to the South to select their candidates. Inspired by this historic occasion, The Prevailing South presents some of the region’s foremost writers, historians and thinkers in an important reevaluation of the South and its role in American politics and culture.

C. Vann Woodward, eminent historian and author of The Burden of Southern History, sets the tone for the collection by defining the South’s new relationship with the rest of the country. He writes:

“The remaining distinctiveness . . . no longer comes at the cost of isolation, withdrawal or intransigence on the part of the South, or rejection and indifference on the part of the rest of the country, as it once did. The South no longer looks to the past for its guidelines, and it faces a future of opportunity and national influence—the promise of once more being wanted and needed.”

Sixteen others join him in recording and analyzing this shift in the thinking of Southerners and non-Southerners alike, touching on almost every significant aspect of American life.

Originally commissioned by the Atlanta Journal and Constitution for the Democratic National Convention, The Prevailing South examines a changing South and a changing America at an unprecedented time in our history. Not since the classic I’ll Take My Stand in the thirties has such an impressive group of writers and thinkers turned their attention to the crucial issues raised in this collection.

Alex Haley also contributed to The Prevailing South: Life & Politics In A Changing Culture by writing the following essay:

Out Of The Past, Into The Convention

In my boyhood in the twenties in Henning, Tennessee (population four hundred seventy-five), my maternal grandfather, proud owner and operator of the W.E. Palmer Lumber Company, occupied something close to the status of a living legend among the blacks who made up roughly half the town’s population. Even the whites gave Grandpa real respect, especially politically.

At no other time was this quite so evident as on Saturday afternoons late in the summer preceding a presidential election. At an early hour on those afternoons, yet another group of local black male personages invited by Grandpa would arrive at our home, each of them clad in his Sunday best. They were a mix of Methodists and Baptists (our family being the former). Some were landowning farmers, though most farmers were renters. There were ministers, both regular and itinerant, plus other church officers and elders. There were building craftsmen, teachers, undertakers, handymen and men of whatever other respectable positions were available in our county of Lauderdale in west Tennessee.

Somberly seated in the living room and the adjoining library and music room in Grandpa’s residence (a house of unprecedented size and substance for a black family in Henning, it is today a Tennessee state museum), all of the men nodded and smiled stiffly. And at the appropriate moment, they held out their calloused and knob-knuckled hands to receive from my matriarchal grandma, my schoolteacher mama and a representative couple of church sisters the light repast of deftly served lemonade and finger sandwich choices of either salmon or chicken salad.

For the next ninety minutes or so, the assembled men would engage in an intense discussion of how the National Republican Party might be moved this year to better address the needs of local black people. It was a futile exercise. The men assembled in that room stood about as close to the Oval Office of a Republican White House as they did to the planet Mars. It was de facto knowledge that the lily-white state Republican Party held utterly no concern for any black interests and clearly did not even want any black colleagues. But Henning’s black Republicans, though marooned within a sea of Democrats in the South, still proudly and persistently carried the tattered banner of their revered Grand Old Party of Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, even though they were not only powerless, but also racially ostracized by that party, as were the blacks of a thousand similar little agrarian townships.

My father later told me that many of the men who met in our home were members of a historic black confederation in the South known as “The Lincoln League.” Its messiah was Mr. Robert Church Jr. (1885 - 1952), who was thought to be “the richest colored man within the U.S. South,” my dad said, and who was without question the most politically powerful black man in the United States at the time.

Remembering boyhood experiences plus the things Dad had told me, as we filmed Roots: The Second Generation, more than half a century later, I included a scene of how my grandpa, after hosting his own round of political meetings, journeyed with Dad, a young professor, to Memphis, where they were among some similarly select gatherings of black leaders invited by Mr. Church Jr. to his mansion.

At this elevated level of black Republican politics, the issues urgently discussed were such questions as what philanthropic monies—Rosenwald, Phelp-Stokes, Carnegie or other—were available for black community schools, libraries, YMCAs or YWCAs or parks. They talked of which cities and towns had priority with those funds, and how further political patronage could be obtained from the National Republican Party and whether visible jobs such as those held by the handful of blacks working already as federal mail clerks and carriers could be expanded in number.

At those meetings, visiting church officials would sometimes pointedly and proudly deposit surplus church funds with the Mr. Church Jr. banking interests. Some other visitors sought the advice of master politician Church on real estate matters. His late father, Mr. Robert Church Sr., had holdings in real estate that were among the largest in Memphis. In fact, during early Reconstruction, Mr. Church Sr. was one of a handful of wealthy men—the wealthiest in Memphis—who personally bought enough municipal bonds to help the nearly bankrupt city regain its charter.

Republican Church Jr. maintained his power even though Memphis was solidly within the Southern Democratic Party structure, autocratically controlled in Memphis by “Boss” Crump. Because it posed no threat to him, Crump, one of the most powerful machine politicians in the country, chose to let the fiefdom of the local black Republican coexist.

Back in our hometown of Henning that November, when the national elections were held, the voting was done by slips of paper that were marked, folded and then dropped into boxes placed in Raines’ Feed Store, which was also where our town’s trials were held. Henning’s black Republicans always were the first voters to arrive on election morning, perhaps a maximum of fifty men, and always one woman, good Baptist sister Scrap Green, who year after year defied all opposition to the exercise of her right to vote. But Sister Scrap, just like the black men, voted quietly and was quickly gone. None of them elected to be around when, later in the day, some whites arrived with their spirits raised by Prohibition whiskey.

It is poignant how little attention history has paid to the fact that from the early years of Reconstruction, in many Southern localities, the Republican Party’s principal custodians were these and similar groups of blacks who voted in each national election as an act of holy ritual, no matter what obstacles were thrust into their paths, including physical threats. And there is irony in the fact that the blacks felt themselves so bonded to the Republican Party of Lincoln—because that helped keep alive the reason the Republican Party tended to be so despised among most whites of the defeated South.

And then, in 1932, a black population impoverished by the century’s greatest depression was swept from their traditional political loyalties by the arrival over the airwaves of the charismatic Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal.

What he had promised when campaigning, he soon backed up after being elected—with his unprecedented, creative programs. None of it was distant or abstract—it was all practical, and personal, reaching literally into lives, into pocketbooks, into the very fields where longtime traditional black Republicans had picked and plowed.

The alphabetical array of NRA, WPA, CCC and FHA represented not only new governmental presences but also new hopes. Indeed, a new spirit was abroad in the land. For the first time, the first time ever, really, the black masses were being dealt with more as human beings, as Americans with the same needs and rights as white people.

One does well to remember the past. It gives a better perspective on some of the things that are happening in the present. It makes me think, for instance, that symbolically, in America today, there could hardly have been a better place than Atlanta for the Democratic National Convention.

Consider that not all that many rains ago, as the homeland Africans say, Atlanta was just one more medium-size, historic city in the South. Today, its commerce and influence stretch to the four corners of the Earth, returning business to enrich the region of the South and the nation of the United States.

It seems somehow fateful—and it seems a wonderful omen—that the city which a century and a quarter ago symbolized the devastation of the South has risen so far, and that it has done it in the last decade and a half under the successive administrations of two black mayors, first Maynard Jackson and now Andrew Young, both of whom, as a fellow Southerner, I’m so proud to call my friends.” ~ Alex Haley.

Alex Haley also wrote the Preface for The Prevailing South: Life & Politics In A Changing Culture: Preface By Alex Haley

(The above essay is presented under the Creative Commons License. The Prevailing South: Life & Politics in a Changing Culture was edited by Dudley Clendinen. © 1988 by the Atlanta Journal & the Atlanta Constitution. All Rights Reserved.)