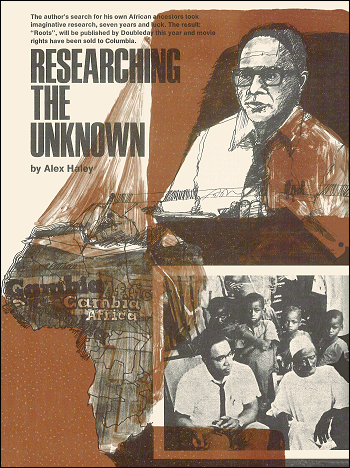

(Researching The Unknown by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1973 issue of Writer’s Yearbook.)

(Researching The Unknown by Alex Haley was originally published in the February 1973 issue of Writer’s Yearbook.)

My family’s seven generations that my Grandma and great aunts told me about during my boyhood have been grasped as the symbol history of all black Americans. Kunta Kinte and his Bell; their Kizzy, her “Chicken George” and his Matilda; their Tom and his Irene (who were the parents of my Grandma) have become, almost overnight, as indelibly a part of the American story as Daniel Boone or Harriet Beecher Stowe. The two-century drama of their lives is already being taught in hundreds of universities, colleges and high schools—replacing the “Uncle Tom” and “Black Sambo” images of U.S. slavery and the Reconstruction eras; and replacing as well the “Tarzan” and “Jungle Jim” images of the peoples of the African continent, physically the second largest on earth.

Part of the reason for all this is that Roots has touched deep within the psyche of a yet wider audience—ALL Americans whose ancestors came from somewhere across an ocean, and the native Americans as well.

Moreover, Roots is being translated into most of the major languages spoken elsewhere. Sometimes I dare to ask myself: is it possible that a miracle is being spread among us, which could reach about the world with a positive effect? I think privately of how my Grandma used to express, “The Lord might not come just when you expect Him to, but He will always be on time.”

The more I reflect upon how Roots came to be, the more I feel that the universal human story is symbolized in this album’s journey to find a family’s past. Roots’ source was true oral history. Wrinkling, greying old ladies sat in their rocking chairs on my Grandma’s front porch in Henning, Tennessee, recalling family stories passed down from generations before themselves. I sat behind my Grandma’s chair, listening. ~ Alex Haley.

Researching The Unknown

My Grandma Cynthia Murray Palmer lived in Henning, Tennessee. (pop. 500), about 50 miles north of Memphis. As I grew up there, we would be visited by several women relatives who were mostly around Grandma’s age, such as my Great Aunt Liz Murray who taught in Oklahoma, and Great Aunt Till Merriwether from Jackson, Tennessee, or their considerably younger niece, Cousin Georgia Anderson from Kansas City, Kansas, and some others. Always after the supper dishes had been washed, they would go out to take seats and talk in the rocking chairs on the front porch, and I would scrounch down, listening, behind Grandma’s squeaky chair, with the dusk deepening into the night and the lightning bugs flicking on and off above the now shadowy honeysuckles. What they most often talked about was the story our family, which had had been passed-down for generations, until there would finally come our bedtime signal, which was the whistling blur of lights of the southbound Panama Limited train whooshing at 9:05 p.m. through Henning.

So much of their talking of people, places and events, I didn’t understand. For instance, what was an “Ol’ Massa,” an “Ol’ Missus,” or a “plantation.” But early I gathered that white folks had done lots of bad thing to our folks, though I couldn’t figure out why. I guessed that all they talked about had happened a long time ago, as now or then Grandma or another would excitedly thrust a finger toward me, exclaiming maybe, “Wasn’t big as this young ‘un!” and that would astound me that anyone as old and grey-haired as they could in any way even relate to my age. But just automatically, in time, my head began both a recording and picturing of the more graphic scenes they would describe, just as I also visualized David killing Goliath with his slingshot, Old Pharaoh’s army drowning, Noah and his ark, Jesus feeding that big multitude with nothing but five loaves and two fishes, and other such wonders which I heard in my Sunday School lessons at our New Hope Methodist Church.

The furthest-back person Grandma and the others ever talked of—always in tones of awe, I noticed—they would call “The African.” They said that some ship brought him to somewhere which they pronounced “ ’Naplis.” They said that then some “Mas’ John Waller” bought him for his plantation in “Spotsylvania County, Virginia.” This African kept on escaping, the fourth time trying to kill the “hateful po’ cracker” slave-catcher, who gave him the punishment choice of castration or of losing one foot. This African took a foot being chopped off with an axe against a tree stump, they said, and he was about to die. But his life was saved by “Mas’ John’s” brother—a “Mas’ William Waller,” a doctor, who was so furious about what had happened that he bought the African for himself, and gave him the name of “Toby.”

Crippling about, working in “Mas’ William’s” house and yard, in time the African met and mated with “the big house cook named Bell,” and there was born a girl named “Kizzy.” She grew up with her African daddy often showing her different kinds of things, and telling her what they were—in his native tongue. Pointing at a banjo, the African uttered, “ko,” as example, or “Kamby Bolong,” pointing at a river near the plantation. Many of his strange sounds started with a “k” sound, and the little, growing Kizzy learned gradually that they identified different things.

When addressed by other slaves as “Toby,” the master’s name for him, the African said angrily that his name was “Kin-tay.” And as gradually he learned more words, of English, he told young Kizzy some things about himself—for instance that he was not far from his village, chopping wood, to make himself a drum, when four men had surprised, overwhelmed, and kidnapped him.

So Kizzy’s head held much about her African daddy when, at age 16, she was sold away, onto a much smaller plantation, in North Carolina. Her new “Mas’ Tom Lea” fathered her first child, a boy whom she named George. And Kizzy told all about his African grandfather to her boy, who grew up into such a gamecock fighter that he was called “Chicken George,” and people would come from all over and “bet big money” on his cockfights. He mated with Matilda, they had seven children, and he told them the stories and strange sounds of their African great-grandfather. And one of those children, Tom, became a blacksmith, who was bought away by a “Mas’ Murray,” for his tobacco plantation in Alamance County, North Carolina.

Tom mated there with Irene, a weaver on the plantation. She also bore seven children, whom Tom now told them all about their African great-great-grandfather—the faithfully passed-down knowledge of his sounds and stories having become by now the family’s prideful treasure.

The youngest of that second set of seven children was a girl, Cynthia—who became my maternal Grandma (which today I can only see as meant). Anyway, all of this is how I was growing up in Henning at Grandma’s, listening from behind her rocking chair as she and the other visiting old women talked of that African (never then comprehended as my great-great-great-great-grandfather) who said his name was “Kin-tay,” and said “ko” for banjo, “Kamby Bolong” for river, and a jumble of other “k”-beginning sounds which Grandma privately muttered while making beds or cooking, and also that near his village he was kidnapped while chopping wood to make himself a drum.

The story had become probably somewhere nearly as fixed in my head as in Grandma’s by when Dad and Mama moved me and my two younger brothers, George and Julius, away from Henning, to be with them at the small black college in Alabama where Dad taught taught agriculture. And compressing my next twenty-five years: more than studying in school, I “daydreamed,” my parents said, preferring the vicarious reading of thrilling adventure books. Then when I was 17, Dad let me enlist as a messboy in the U.S. Coast Guard. Becoming a ship’s cook out in the South Pacific during World War Two, and at nights down by my bunk I began trying to write sea adventure stories, mailing them off to magazines, and collecting rejection slips for eight years before some editors began purchasing and publishing occasional stories. By 1949, the Coast Guard made me its first “journalist”; finally with 20 years’ service, I retired at the age of 37, as a Chief Journalist, determined now to make a new career of full-time writing. After awhile of floundering, I wrote mostly on assignments for the Reader’s Digest; then for Playboy I happened to start their “Interviews” feature, my successive subjects being controversial personages, one among them the late Malcolm X. Then, my first book attempt took a full year of really exhaustively interviewing him, and another year of writing, in the first-person, as if he did, The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

In Washington, D.C. one Saturday in 1965, I just happened to be walking past the U.S. Archives. Across the interim years, I had thought often of Grandma’s old stories—I can’t reason otherwise what diverted me up the Archives’ steps. And when a main reading room desk attendant asked could he help me, I wouldn’t have dreamed of admitting to him some curiosity hanging on from boyhood about slave forebears I’d then heard of. I kind of bumbled that I was interested in census records of Alamance County, North Carolina, just after the Civil War.

The microfilm rolls which were delivered, I kept turning through the machine, and with a building intrigue—viewing in different Census-takers’ penmanship what seemed an endless parade of the names of people, then as living and walking around as anyone on earth, but who one day were gone forever. But after microfilmed roll after roll of it, I was beginning to tire when, in utter astonishment—I looked upon the names of Grandma’s parents. Tom Murray, Irene Murray . . . older sisters of Grandma’s, as well—Grandma wasn’t even born yet . . . names, every one of them, that I’d heard countless times on her front porch.

It wasn’t that I hadn’t believed Grandma. You just didn’t not believe my Grandma. It was simply uncanny, the actually seeing those names in print . . . moreover, in some official U.S. Government records.

Across the next several months, whenever possible I was back in Washington, searching, in the Archives, the Library of Congress, the Daughters of the American Revolution Library. (Wherever black attendants got some idea of my search, documents I requested reached me miraculously quickly.)

I moved into the Library of Congress with research because I had learned in National Archives of the genealogical leads sometimes turned up in studies of counties—and the Library of Congress had practically interminable county records. I learned, working among these, that one had to first check the histories of counties themselves, as many had been made larger (or smaller) at various times, via annexations . . . and this could bear upon finding records of families in that listed county at certain dates.

In one source or another, in 1966 I was able to document at least the highlights of the cherished family story. I would have given anything to tell Grandma but sadly, in 1949 she had gone. So I went and told the only survivor of those Henning front-porch storytellers, Cousin Georgia Anderson, now in her 80’s in Kansas City, Kansas. Wrinkled, bent, not well herself, she was so overjoyed, repeating to me the old stories and sounds; they were like Henning echoes: “Yeah, boy, that African say his name was ‘Kin-tay’; he say the banjo was ‘ko,’ an’ the river ‘Kamby-Bolong,’ an’ he was off choppin’ some wood to make his drum, when they grabbed ‘im!” Cousin Georgia grew so excited we had to stop her, to calm her down. “You go ‘head, boy! Your grandma an’ all of ’em—they up there watchin’ what you do!”

That week, Playboy editor Murray Fisher telephoned me to fly and do an interview in London. Given my longtime steeping in the old, in the past, scarcely a tourguide missed me—rubbernecking, awed, at so many historical places and other treasures I’d heard of, and read of. I came upon the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum, marveling anew at how Jean Champollion, the French archaeologist, had miraculously deciphered its ancient demotic and hieroglyphic texts . . .

The thrill of that just kept hanging around in my head. I was on a jet returning to New York when a thought hit me. Those strange, unknown-tongue sounds, always part of our family’s old story . . . they were obviously bits of our original African “Kin-tay’s” native tongue. What specific tongue? Could I somehow find out?

Back in New York, I began making visits to the United Nations Headquarters’ lobby; it wasn’t hard to spot Africans. I’d stop any whom I could, asking if my bits of phonetic sounds held for them any meaning? A couple of dozen Africans quickly looked at me, listened, and took off—understandably, from some Tennesseean’s accent alleging “African” sounds.

An expert researcher friend, George Sims (we grew up together in Henning), brought me some names of ranking scholars of African linguistics. Particularly intriguing was one, a Belgian- and English- educated Dr. Jan Vansina; he had spent his early career living in West African villages, studying and tape-recording countless of the oral histories which were narrated by certain very old African men; and Dr. Vansina had written a standard textbook, The Oral Tradition.

(A freelancer who didn’t have a good friend like George Sims could also locate the names of some linguistic specialists in the Directory of American Scholars, or through the Linguistic Society of America.)

So I flew to the University of Wisconsin where Dr. Vansina was. In their living room, I told him every bit of the family story, to the fullest detail I could remember it. Then, intensely, he queried me, about the story’s physical relay across the generations, about the kind of gibberish of “k” sounds which sometimes Grandma had fiercely muttered to herself while doing her housework, with my brothers and me giggling beyond her hearing at what we had dubbed “Grandma’s noises.”

Dr. Vansina finally said, his manner very serious, “These sounds your family has kept sound very probably of the tongue called ‘Mandinka’.”

I’d never heard of any “Mandinka.” Grandma just told of the African saying such as “ko” for banjo, or “Kamby Bolong” for a Virginia river.

Among Mandinka stringed instruments, Dr. Vansina said, one of the oldest was the “kora.”

“Bolong,” he said was clearly Mandinka for “river.” Preceded by “Kamby,” very likely it meant “Gambia River.”

Dr. Vansina telephoned an eminent Africanist colleague, Dr. Philip Curtin. He said that the phonetic “Kin-tay” was correctly spelled “Kinte,” a very old clan which had originated in Old Mali. The Kinte men traditionally were blacksmiths, and the women were potters and weavers.

I knew I must get to the Gambia River.

The first native Gambian I could locate in the U.S. was named Ebou Manga, then a junior attending Hamilton College in upstate Clinton, New York. He and I flew on Pan American to Dakar, Senegal, then took a smaller plane to Yundum Airport, and rode in a van to The Gambia’s capital, Bathurst. Ebou and his father assembled eight Gambia government members. I told them Grandma’s stories, every detail I could remember, as they listened intently, then reacted. “ ’Kamby Bolong’ of course is Gambia River!” I heard. “But more clue is your forefather’s saying his name was ‘Kinte’.” Then they told me something I never would have even fantasized—that in places in the back country lived very old men, commonly called griots, who could tell centuries of the histories of certain very old family clans. As for Kintes, they pointed out to me on a map some family villages, Kinte-Kundah, and Kinte-Kundah Janneh-Ya, for instance.

The Gambian government members said they would make efforts to aid me. I returned to New York dazed. It is embarrassing to me now, but only to tell the truth: despite Grandma’s stories, I’d never been concerned much regarding Africa, beyond its location on world maps, and I held the routine illusions of African people mostly among exotica jungles. But such a compulsion now laid hold of me to learn all I could that I began devouring books about Africa, especially circa the slave trade. Then one Thursday’s mail contained a letter from one of the Gambian officials, inviting my return there.

Monday I was back in Bathurst. It simply galvanized me when the officials said that a griot was located who told the Kinte clan history—his name was Kebba Kanga Fofana. To reach him, I discovered, required a modified safari, renting a launch to get upriver, two land vehicles to carry supplies by a roundabout, longer land route, and employing finally fourteen people, including three interpreters and four musicians, as a griot would not speak the reversed clan histories without background music.

The boat Baddibu vibrated upriver, with me acutely tense: were these Africans maybe viewing me as but another of the pith-helmets? After about two hours, we put in at James Island, for me to see the ruins of once British-operated James Fort, where two centuries of slaveships had loaded thousands of cargoes of Gambian tribespeople. The crumbling stones, the deeply oxidized swivel cannon, even still some remnant links of chains, seemed all but impossible to believe—but there they were to gaze at. Then we continued upriver to the left-bank village of Albreda, and there put ashore, now to continue on foot to the Juffure village of the griot. Once more we stopped, for me to see Toubob kolong, meaning “The white man’s well,” now almost filled in, and in swampy surrounding area, with abounding tall, saw-toothed grass, a century since it was dug to “seventeen men’s height deep,” to insure survival drinking water for long-driven, famishing coffles of slaves recently taken.

Walking on, I kept wishing that Grandma could hear how her stories had led me to the “Kamby Bolong.” (Our surviving storyteller Cousin Georgia died in a Kansas City hospital during this morning, I would learn later.) Finally, Juffure village’s playing children, sighting us, flashed an alert. The 70-odd people came rushing from their circular, thatch-roofed, mud-walled huts, with goats bounding up and about, and parrots squawking from up in the palms. I sensed him in advance somehow, the small man amid them, wearing a pillbox cap and an off-white robe—the griot. Then the interpreters did go to him, as the villagers thronged around me.

And it hit me like a gale wind: every one of them, the whole crowd, were jet black. A sense of some enormous guilt swept me . . . sense of being some kind of hybrid—sense of being impure, among pure. It was a very awful sensation.

The old griot, stepping away from my interpreters, quickly was swarmed around by the crowd—all of them buzzing. An interpreter named A. B. C. Salla came to me; he whispered: “Why they stare at you so, they have never seen here a black American.”

The impact of that hit me: I was symbolizing for them twenty-five millions of us they had never seen. What did they think of me—of us?

Then abruptly the old griot was briskly walking toward me. His eyes boring into mine, he spoke in Mandinka, as if instinctively I should understand—and A. B. C. Salla translated:

“Yes . . . we have been told by the forefathers . . . that many of us from this place are in exile . . . in that place called America . . . and in other places.”

I suppose I physically wavered, and they thought it was the heat; rustling whispers went through the crowd, and a man brought me a low stool. Now the whispering hushed—the musicians had softly begun playing kora and balafon, and a canvas sling lawn seat was taken by the griot, Kebba Kanga Fofana, aged 73 “rains” (one rainy season each year). He seemed as if gathering himself into a physical rigidity. And he began speaking the Kinte clan’s ancestral oral history; it came rolling from his mouth across the next hours . . . 17th and into 18th century Kinte lineage details, predominantly what men took what wives; the children they “begot,” in the order of their births; those children’s mates and children. When things had taken place frequently was dated by some proximate singular physical occurrence. It was as if indelible within the griot’s brain was some ancient scroll. Each few sentences or so, he would pause for an interpreter’s translation to me. I distill here to a lineal very essence:

The Kinte clan began in Old Mali, the men generally blacksmiths “—who conquered fire,” and the women were potters and weavers. One large branch of the clan moved into Mauretania . . . from where one son of the clan, Kairaba Kunta Kinte, a Moslem marabout holy man, entered The Gambia. He lived first in the village of Pakali N’Ding; he moved next to Jiffarong village; “—and then he came here, into our own village of Juffure.”

In Juffure, Kairaba Kunta Kinte took his first wife, “—a Mandinka maiden, whose name was Sireng. By her, he begot two sons, whose names were Janneh and Saloum. Then he got a second wife, Yaisa. By her, he begot a son, Omoro.”

The three sons became men in Juffure. Janneh and Saloum went off and found a new village, Kinte-Kundah Janneh-Ya. “And then Omoro, the youngest son, when he had thirty rains, took as a wife a maiden, Binta Kebba.

“And by her, he begot four sons—Kunta, Lamin, Suwadu, and Madi . . .”

Sometimes, a “begotten,” after his naming, would be accompanied by some later-occurring detail, perhaps as “—in time of big water (flood), he slew a water buffalo.” Having named those four sons, now the griot stated such a detail.

“About the time the king’s soldiers came, the eldest of these four sons, Kunta, when he had about sixteen rains, went away from this village, to chop wood to make a drum . . . and he was never seen again—”

Goose-pimples the size of lemons seemed popping all over me. In my knapsack were my cumulative notebooks, the first of them including how in my boyhood, my Grandma, Cousin Georgia and the others told of the African “Kin-tay” who always said he was kidnapped near his village—while chopping wood to make a drum . . .

Somehow, I showed the interpreter; he showed and told the griot, who excitedly told the people; they grew very agitated. Abruptly then they formed a human ring, encircling me, dancing and chanting. Maybe a dozen of the women carrying their infant babies rushed in toward me, thrusting forth the infants into my embracing efforts—conveying, I would later learn, “—the laying on of hands . . . through this flesh which is us, we are you, and you are us.” The men hurried me into their mosque, their Arabic praying later being translated outside: “Thanks be to Allah for returning the long lost from among us.” Direct descendants of Kunta Kinte’s blood brothers were hastened, some of them from nearby villages, for a family portrait to be taken with me . . . surrounded by actual ancestral sixth cousins. More symbolic acts filled the remaining day.

(Conversations to the Moslem religion came circa 1400’s. The Kintes in Old Mali were Moslems and conversions among the tribe later were via the traders from North Africa, most of them Moslems, and great proselytizers.)

When they would let me leave, somehow I wanted to go away over the African land. Dazed, silent in the bumping land rover, I heard the cutting staccato of talking drums. Then when we sighted the next village, its people came thronging to meet us. They were all—little naked ones to wizened elders—waving, beaming, amid a cacophony of crying out; and then my ears identified their en masse words: “Meester Kinte! Meester Kinte!”

Let me tell you something: I am a man. But I remember the surging sob from my feet, flinging up my hands before my face and bawling as not since I was a baby . . . the jet-black Africans were jostling, staring . . . I didn’t care, with it surging that if you really knew the odyssey of us millions of black Americans, if you really knew how we came in the seeds of our forefathers, captured, driven, beaten, inspected, bought, branded, chained in foul ships, if you really knew, you needed weeping . . .

Back home, I knew that what I must write, really, was our black saga, where any individual’s past is the essence of the millions’.

I was now flat broke. The first trip to Africa with Ebou Manga cost about $2,000 and by the second trip with the entourage I had spent $5,000. (By now, I have spent about $80,000 in the seven years of work on this book.)

I went to some editors I knew, describing the Gambian miracle, with my aim now for saturation further research; Doubleday contracted to publish, and Reader’s Digest to condense the projected book, then I had advances to travel further.

Tantalizing me was what ship brought Kinte to Grandma’s “Naplis”—Annapolis, Maryland, obviously. But a key was when? The old griot’s time reference to “king’s soldiers” sent me flying to London. Feverish searching at last identified, in British Parliament records, “Colonel O’Hare’s Forces,” dispatched in mid-1767 to protect the then British-held James Fort whose ruins I’d walked among. So Kunta Kinte was down in some ship sailing probably later that summer from the Gambia River to Annapolis.

Now I feel it meant that I had taught myself to write in the U.S. Coast Guard. For the sea dramas I then concentrated upon had seen me experience years of their researching among many varieties of yellowing old U.S. maritime records. So now somewhat familiarly in English 18th Century marine records, finally I tracked ships reporting themselves in and out to the Commandant of the Gambia River’s James Fort. And then early one afternoon: a Lord Ligonier under a Captain Thomas Davies had sailed on the Sabbath of July 5, 1767, her cargo: 3265 elephants’ teeth, 3700 pounds of beeswax, 800 pounds of cotton, 32 ounces of Gambian gold, and 140 slaves—her destination “Annapolis.”

That night re-crossing the Atlantic, in the Library of Congress her Annapolis arrival was one brief line in “Shipping In The Port of Annapolis—1748-1775” I located the author, Vaughan W. Brown, in his Baltimore brokerage office. He drove to Annapolis’ Historical Society, finding me further documentation of her arrival on September 29, 1767. (Exactly two centuries later, September 29, 1967, standing, staring seaward from an Annapolis pier, again I knew tears.) More help came there in the Maryland Hall of Records. Archivist Phebe Jacobsen found the Lord Ligonier’s arriving Customs declaration listing, “98 Negroes”—so in her 86-day crossing, 42 Gambians had died, one among the survivors being 16-year-old Kunta Kinte. Then the microfilmed October 1, 1767, Maryland Gazette contained, on page two, an announcement to prospective buyers from the ship’s agents, Daniel of St. Thos. Jenifer and John Ridout (the Governor’s secretary): “—from the River GAMBIA, in AFRICA . . . a cargo of choice, healthy SLAVES . . .”

I’ve by now all but commuted between sources finally on four continent of the 18th Century’s nautical history or African culture. One morning, the British Nautical Museum’s director said, “The greatest authority on wooden ships is Howard Chapelle at your Smithsonian.” The next day in Washington, Dr. Chapelle told me of the New England-built Lord Ligonier’s likely oaken keel and hull timbers, with wedged black locust pegs affixing her planking of loblolly pine and hackmatac cedar. In Europe, Africa, the West Indies and Brazil, I have dug for all true 1700’s African culture I could find—for my coming book to synthesize and weave it about Kunta Kinte from his birth and across his next 16 years to his kidnapping . . . by when, hopefully, no reader ever again will feel slavery as something only statistical and abstract (as if you would feel Hitler’s Germany, read “The Diary of Ann Frank”). When I faced writing of Kunta’s slaveship crossing, flying to Africa, boarding a U.S.-bound freighter African Star, nightly I slipped to a dark, cold corner in her depths, stripping to my underwear, trying to feel with Kunta.

From Annapolis, the book will trek across the next two centuries with Kunta and his descendants; then Roots (to be the book’s title) will climax with one among the seventh generation, myself, having today the mission of its writing. Roots is to be published in September 1973, by Doubleday, and Columbia Pictures has taken its movie rights, planning a massive picture to be filmed in The Gambia and the southern United States.

I have told of some of my searching successes, and not of many quests which have met with failures yet cankering within me. Is there anybody who can help me to document my great-great Grandpa “Chicken George” Lea’s sailing to England, circa the 1850’s? Grandma and Cousin Georgia always told of a “rich Englishman” hiring away the great slave gamecocker from Tom Lea. They said this Englishman took “Chicken George” on a ship “to fight his roosters against anybody’s” in English, then French gamecock pits. Then returning to North Carolina, and being given his freedom by his father-master, shortly before the Civil War, “Chicken George” next was in the gory Battle Of Fort Pillow. I’ve dug into accounts of cockfighting in North Carolina, in England, and with interpreters in France; what little I have been able to find was finally from cockfighting historian Robin Walker, in Glasgow, Scotland. Whoever may know of any promising sources, please write me c/o 898 National Press Building, Washington, D.C. 20004.

Only briefly in the book will be another lineage facet, whose further extensions I can actually regard but technically. Also during boyhood, we would visit Dad’s mother. She was small, very fair, blonde, with blue eyes and such quickness of movements that she had always been called “Cricket.” Grandma Haley often told of her girlhood on a plantation in Alabama, where her mother was “Easter,” a slave, and her father was a Civil War colonel. Well, just curious, I identified the colonel in microfilmed census rolls in the U.S. Archives, and also his father. Then I found that the father had come to America in 1799—from his native County Monoghan, Ireland. That rocked me: I’d never feel within any Irish. But sheer curiosity kept bugging until I flew to Ireland, tracing the colonel’s lineage finally back as far as 1707, in a little town of Carrickmacross, where once again I got rocked: they were most hospitable—until they learned I’m Protestant.

Some of my finds still register to me as miracles. There have been other occurrences by now, which I could no more have dreamed of, as when recently the Librarian of Congress, L. Quincy Mumford, introduced me to tell a large audience there of Roots’ seven-year researching. I anticipate misting eyes again in July when I will speak for an African culture conference at the University of London. But an entirely chance audience produced my most sheerly incredible occurrence. In New York one morning, W. Colston-Leigh who arranges my lectures asked if I’d rush to a plane to fill an ailing client’s place that night at a Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. Barely making it, I spoke of my long search—then the Academic Dean Waller Wiser told me that from things I’d said, he knew he was of the seventh-generation from the Wallers of Spotsylvania County, Virginia, who had bought my forefather. The college since has given me the honorary Doctorate of Letters, with Waller presenting it. Every time that he and I get the chance to talk now, we speculate upon why our meeting after 200 years?

And of course deeply subjective discussions occur these days with my two younger brothers, both now Washingtonians, George as the Administration’s Chief Counsel of Urban Mass Transportation, and Julius a Navy Department architect. We are giving to our ancestral Juffure village a new mosque—as a personal symbol. But Kunta Kinte really was but one among those many millions of enslaved African forebears, whose seeds are the black generations of North and South America and the West Indies. Just recently, we have obtained a District of Columbia nonprofit incorporation of The Kinte Foundation. It exists to create a black genealogical library where one belongs—in the capitol of the United States—where the U.S. Archives, the Library of Congress, and the D. A. R. Library are located.

My researching discoveries have included that an unsuspected wealth records do exist which identify slaves and early free blacks. In antebellum documents in innumerable courthouses and libraries; in countless homes’ old trunks, and chests, and attics; in no end of other places, there are plantation slave lists; records of slaves sold, bought, hired-out, and runaways; there are slave traveling passes, manumission or freedom papers; there are wills bequeathing slaves, lists of black churchgoers, blacks’ marriage records; and old personal diaries, journals, notebooks and letters which contain the names of pre-1900’s blacks—to give but a few examples of what the library must gather. Any reader’s awareness of such documents, originals or copies, which possibly may be available for the Kinte Library, we wish very much to know of. Similarly, early black identification records must be acquired from the other countries where Africans were taken—as well as the vital and rich black oral history on both sides of the Atlantic. The Kinte Foundation plans to aid African universities and colleges to select students to tape-record venerable local tribal griots narrating ancestral clan lineages—the copied tapes, with translations, to be available for use as one audio-feature of this singular library.

One result naturally will be a widening of the potentials that at last more U.S. black people also may be able to search out extended lineages—with even back-to-African ancestries possible for some extremely blessed few. But the coming Kinte Library’s main focus is that its greatest possible collection of black ancestry has to further the resurrecting of the U.S. black heritage which has been almost destroyed. “People are lost who do not know their roots” is a saying among native Africans, who averagely grow up knowing specifics about generations of their forefolk.

The U.S. Coast Guard has invited me to be its guest late this summer, sailing on the great three-masted Cadet training ship EAGLE to Germany, for the Summer Olympics regatta of the world’s only 18 remaining “tall ships.” I write at my best at sea; it is where I wrote that first million words. Somewhere out there, finally I will finish writing Roots, a saga of what centuries of U.S. and other black eyes and lives have seen and experienced since being torn from Africa in our forefathers—as is comprehended rarely because, as is universally the case, the histories have been written by the winners. ~ Alex Haley.

(Researching The Unknown by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the February 1973 issue of Writer’s Yearbook. © 1972 Alex Haley. © 1973 Writer’s Yearbook. All Rights Reserved.)