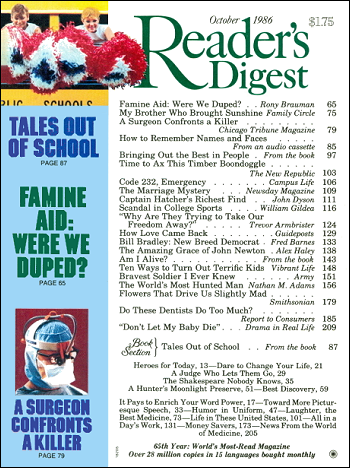

(The Amazing Grace of John Newton by Alex Haley was originally published in the October 1986 issue of Reader’s Digest. In 2007, Reader’s Digest republished the article in Alex Haley: The Man Who Traced America’s Roots.)

(The Amazing Grace of John Newton by Alex Haley was originally published in the October 1986 issue of Reader’s Digest. In 2007, Reader’s Digest republished the article in Alex Haley: The Man Who Traced America’s Roots.)

“To the editor: Haley Was No Stranger To Shoals Area by Features Editor Terry Pace (February 11, 1992) recounting Alex Haley’s several visits and personal connections with our community was read with much interest.

“In recalling Mr. Haley’s visit in 1989 to the Florence Alabama Reunion Celebration there was one event in which he was the guest speaker that was especially moving and symbolically profound. The event was the Sunday morning worship service in the sanctuary of the First Presbyterian Church of Florence.

“The same sanctuary where James Jackson of the Forks of Cypress and his family, as charter members, attended services and in all probability where the ancestors of Alex Haley also attended, since prior to the Civil War slaves often attended church with their masters and sometimes were considered members.

“The dynamics of the place and the occasion, were brought to a profound symbolic focus when Mr. W. H. Mitchell, an Elder of the First Presbyterian Church and a descendant of one of the Jackson family, graciously introduced the honored guest speaker, a descendant of one of the slaves on the Jackson plantation at the Forks of Cypress. It was one of those special moments of grace that words cannot describe.

“Appropriately Mr. Haley, the teller of stories, proceeded to tell the familiar story of how John Newton, at one time the captain of a slave ship in the 18th century, was converted to Christianity and eventually became the author of one of the great hymns of the church, Amazing Grace. This incident encapsulates my fondest memory of Alex Haley.” ~ Irving G. Rudolph. (Published in the TimesDaily on February 17, 1992)

The Amazing Grace of John Newton

John Newton was born in London on July 24, 1725, to a pious and shy mother and an authoritarian father. To the boy’s relief, his shipmaster father would spend only a few weeks at home between year-long voyages.

When John was seven, his mother died of tuberculosis, The shipmaster, practical man that he was, remarried before his next voyage; for John, however, the loss of his mother was devastating. He became stubborn, disrespectful and difficult, and soon was packed off to a boarding school.

There he was confronted with a headmaster who wielded a cane and a birch rod. The experience “almost broke my spirit,” he later confided in a letter. But more torment was in store.

At age 11, John was put to sea as an apprentice sailor on his father’s ship. During this time he strayed further and further from his mother’s religious teachings.

By his teens, he was an expert sailor, but his father apprenticed him to a merchant at Alicante, Spain. The 15-year-old disobeyed orders, fought with anyone who crossed him, and was sent back because of his unsettled behavior. As he later confessed, “I believe for some years I never was an hour in any company without attempting to corrupt them.”

Next his father arranged for John to learn the plantation business in Jamaica. Before leaving, the youth went to visit his mother’s relatives in Chatham, England, and, in one of the twists of circumstance that filled Newton’s life, met and fell in love with Mary Catlett, not quite 14. Mary reminded him of his mother. So smitten was John that he prolonged the visit and missed his ship.

Months later he was impressed into the British navy. In 1745, midshipman Newton set sail for the East Indies on the H.M.S. Harwich. The voyage was to last five years, but a storm hit and the Harwich had to anchor off Plymouth, England. Newton was put in charge of a boat going ashore, with instructions to see that none of the crew deserted. Lovesick and headstrong, John himself escaped. Afraid to ask for directions to Chatham, he walked for two days before he was arrested by a military patrol and returned to the Harwich. There he was put into irons, stripped and flogged as a deserter, then transferred to a ship that ranked lowest in the maritime world—a ship engaged in the slave trade. “From this time I was exceedingly vile,” he later confessed.

The female slaves on board were at the crew’s disposal. John Newton, not quite 20 and now a militant atheist, indulged his sexual appetites as often as he wished. He was a far cry from the studious child who had sung hymns at his mother’s knee.

In Sierra Leone, he left the ship to work for a slave dealer, a white man named Clow. Clow’s common-law African wife hated John; when he fell desperately ill, she denied him food and water, and had her own black slaves torment him. Miraculously, Newton survived, but only to live in virtual bondage for more than a year on Clow’s plantation. His life had reached its nadir.

Newton’s father had urged a ship-owning friend in Liverpool to ask all captains of his slave ships working along the African coast to search for John and to bring him home. In February 1747 the ship Greyhound put in at a port in Sierra Leone, and Newton—through a series of divine interventions, he would later say—was found.

The Greyhound was on a long trade cruise, returning to England via Brazil. Seeking something to do, Newton began reading The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas à Kempis, a classic study of spiritual life that included warnings of God’s judgment. Disturbed by the book’s message, he flung it aside. It was March 9, 1748, the turning point of Newton’s life.

In the dark, early-morning hours of the next day, the Greyhound was struck by a sea so heavy that part of her side was stove-in. “Pumping’s useless! Nothing can save this ship, or us!” a veteran sailor exclaimed. But Newton and others did pump from 5 a.m. until noon. “If this will not do, the Lord have mercy upon us!” Newton cried out, startled by his own words.

The Greyhound did survive, and when she finally limped into Liverpool she carried a different John Newton from “the blasphemer” who had been plucked from the African coast. As he later explained, “I began to know there is a God that hears and answers prayer . . . though I can see no reason why the Lord singled me out for mercy.” (For the rest of Newton’s life, he prayed and fasted on each anniversary of that fateful March morning.)

Troubled Conscience. Newton rushed to Chatham to see Mary, and after a voyage as first mate on a slave ship, John Newton, 24, married Mary Catlett, 20.

For the next four years, John captained slave ships. At first he had no scruples about slave trading, which was considered respectable and essential to Britain’s prosperity. But as his new faith steadily grew, he wrestled with his conscience. Twice each Sunday he began conducting his white crew in prayers as the chained Africans lay closely packed, some of them dying, on the opposite side of the ship.

During his next two voyages to Guinea, buying and selling blacks, he tried to act mercifully toward them. Then in 1754, while Newton was sitting at home drinking tea with Mary, he suffered a minor stroke. He recovered, but it was clear that his days at sea were over.

A Growing Flock. Newton was appointed the official Liverpool tide surveyor in 1755. With time on his hands, he studied Latin, mathematics and the Scriptures. He also wrote hymns and began to preach occasionally as a lay evangelist. Increasingly he felt the call to enter the ministry.

In 1764 the new Rev. John Newton, 39, was appointed the curate of Olney, a little village on the bank of the River Ouse in Buckinghamshire. Newton loved his Olney parishioners. “Brothers and sisters” he called them. Many were poor, uneducated lacemakers. Not only did he wear his old sea coat on his rounds to the sick and needy, but he also told stories from the pulpit of his seafaring life, his great sins and his own unworthiness to preach the Gospel.

Moreover, Newton dared to replace the conventional psalm-singing with the singing of hymns that were simple enough to be understood and felt by the plain people. When Newton published An Authentic Narrative in 1764, a graphic first-person record of his past debauchery and rescue, so many people flocked to his church that a new gallery had to be added.

After 15 years, Newton of Olney was reassigned to St. Mary Woolnoth, a distinguished church in London. Though his new position brought him great influence and social status, he never lost the image of himself broken and wretched on the coast of Africa, hating God and his own soul. His constant message, even to London’s elite, was that he himself was living proof that God could save the very worst.

In 1785, in yet another twist of faith, Newton crossed paths with a popular young political figure named William Wilberforce. Only 26 and already a member of Parliament, Wilberforce had recently experienced a religious awakening. Though his friends predicted a great political career, Wilberforce was convinced that his privileged life had no purpose.

A Trump Card. Years before, Newton had been a friend and neighbour of Wilberforce’s aunt, and as a youngster William had come under Newton’s spell. Now “reborn,” Wilberforce sought out the 60-year-old Newton for spiritual counsel. Should he resign from Parliament and enter the ministry? No, advised Newton. God can make you “a blessing both as a Christian and statesman.”

Wilberforce, who was looking for a cause, found it in Newton’s sermons against slavery. This was an issue that no political party would dare touch, but no true Christian could evade.

Newton joined the battle as best he could, though his health was failing. He alone in the political arena spoke from personal experience, a trump card the opposing forces were unable to counter. He addressed the Privy Council (including Prime Minister William Pitt): “The slaves lie in two rows, one above the other, on each side of the ship, like books upon a shelf. The poor creatures are in irons, both hands and feet. . . . And every morning more instances than one are found of the living and the dead fastened together.”

In March 1807, Parliament passed Wilberforce’s bill abolishing the slave trade on British ships. That same year, on December 21, the Rev. John Newton, 82, spoke his last words: “I am a great sinner . . . and Christ is a great Saviour.”

Newton was buried beneath his church of St. Mary Woolnoth, and a tablet was placed on the church wall, with an inscription he had written himself: “John Newton, clerk, once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa, was by the rich mercy of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ preserved, restored, pardoned, and appointed to preach the faith he had long labored to destroy.”

My research brought me to St. Mary Woolnoth. I stood on the very rostrum where the Rev. John Newton had held his congregation spellbound with stories of the sea, his sins and God’s great mercy. As I looked out over the empty pews, the organist played the melodies of Newton’s hymns. One glorious tune swelled up all around me. The verses were written at Olney—a minor autobiographical lyric that critics say is a poor example of Newton’s work. But that hymn has traveled the world, bringing a message of hope and forgiveness to all people of faith.

I sang to myself the simple words I had learned as a child in a black church in the American South. You know them too:

Amazing grace—how sweet the sound—

That saved a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

(The Amazing Grace of John Newton by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the October 1986 issue of Reader’s Digest. © 1986, 2007 The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc. All Rights Reserved.)