(We Must Honor Our Ancestors by Alex Haley was published in the August 1986, November 1990 and August 1993 issues of EBONY.)

(We Must Honor Our Ancestors by Alex Haley was published in the August 1986, November 1990 and August 1993 issues of EBONY.)

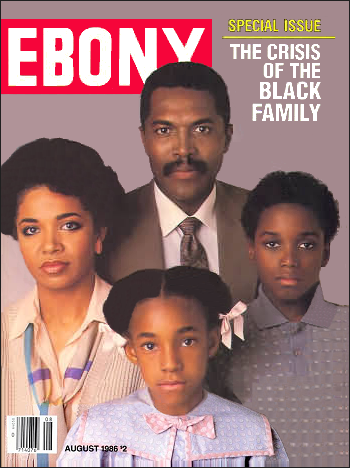

One way to confront and resolve the crisis of the Black family is for Blacks to honor their ancestors because it strengthens the family unit. That view is expressed by author Alex Haley in the August 1986 EBONY Special Issue: The Crisis Of The Black Family. “I always urge how much we need to remind ourselves that, except for the endurance of our historic ancestors . . . we surely wouldn’t be enjoying today’s positive potentials and opportunities,” says Haley, author of the historic novel, Roots: The Saga of An American Family.

Haley’s novel became an acclaimed television mini-series and is a prime example of his belief of how important it is to treasure our ancestors. Haley says, “Their strength and courage made it possible for our race to survive the physical and psychic atrocities through slavery and the Reconstruction Era.”

Experts interviewed in the August EBONY say Black families desperately need the Black church and school to keep the family unit from deteriorating. Observing that Black people have forgotten that it is their spiritual heritage that has brought them to where they are today, Rev. Clay Evans, pastor of Chicago’s Fellowship Baptist Church, says: “I urge them to get back in the church where moral principles are being taught and where the Word of God is being preached.”

Despite repeated attempts to destroy it, the Black family has endured. It survived forced separation of husbands and wives, parents and babies, brothers and sisters during slavery. Adverse social forces and the stresses of urban life have battered it for generations, yet it remains intact, strong perhaps because of the annealing process imposed by hard times.

We Must Honor Our Ancestors

Among the myriad problems that demand our most serious concerns about the Black family nowadays, the saddest one to me is that our Black youths have little or no knowledge, or—worse yet—no comprehension of the awesome strength, courage and resilience of our ancestors. It was those attributes that enabled our race to survive the physical and psychic atrocities and traumas which characterized Blacks’ existence through slavery and the Reconstruction era.

Back then, circular flat rocks often were used to mark our ancestors’ final resting places. Occasionally, some of these can still be found, deeply weathered and eroded, although most of those stones have disappeared forever. Now, whenever and wherever I am privileged to speak to largely Black audiences, I always urge how much we need to remind ourselves that, except for the endurance of our historic ancestors beneath those rock markers, we surely wouldn’t be enjoying today’s positive potentials and opportunities—a relative plethora of them which, in fact, our ancestral Blacks couldn’t even have conceived.

In an effort to convey some greater sense of the flow, of the interaction, of our dead and also living generations, I try to share whenever I can—especially with young Black audiences—how that was explained in Roots by the father Omoro Kinte to his son, Kunta Kinte, who was weeping about the death of his beloved Grandma Yaisa. “My son, now is time to tell you that every village has, actually, three different sets of people. First there are those whom your grandmother has just joined in eternity. Then the second set of people are those like you and me, now here walking around and talking amidst our brothers and sisters within our village, and in neighboring villages. And our third set of people are those yet unborn, my son. They are seeds in your and your playmates’ loins, who quicker than we can realize will replace first me and then you when also we will join your grandmother in eternity.”

Here now in our swiftly paced technological era, it seems to me that not only younger Black people, but we older ones as well, need urgently to show our living grandparents’ generation that we do realize and respect and honor how much we have inherited and benefited because of the experiences which they survived. In fact, these days when we hear so much of our need to strengthen Black families—which indeed we do—may I speak out that we must turn around especially one inevitably weakening process, which is that fewer and fewer Black children are experiencing yesteryear’s close exposures to loving grandparents. I think that nobody else can give children—especially toddlers through pre-teens—quite that irrational love of grandparents. In their own singular way, grandparents somehow sort of sprinkle a sense of stardust over grandchildren.

Symbolizing for me both the ancestral contribution along with their love is an annual human drama to be witnessed at small Southern Black colleges’ commencement exercises: Always the auditorium is jam-packed (and it usually is also hot). Of course, the graduating class is seated facing the stage, and their families usually are seated as a bloc at rear right. Among the grandfatherly aged men—often farmers—a goodly percentage are wearing what is probably their only suit, and the grandmotherly ladies are wearing their choicest Sunday frocks.

Maneuver yourself close enough and in these grandparents’ weathered faces, and their often knobby-knuckled, work-worn hands is a special sort of visual history and heritage lesson. These dear elders—bless their hearts—have seen and endured so much! They just sit there like graven images, staring straight ahead at wondrous happenings up on the stage. It may well be their first time ever on any college’s grounds, which represents relatively hallowed grounds to them, for attending any college was even beyond dreaming in their lives.

And that is why their grandchild (sometimes great-grandchild) who is seated somewhere up front, wearing the academic hood and gown, means more than mere words could ever express—starting with the fact that very likely it’s the extended family’s very first college graduate. That already will have caused the whole family to go around walking a little taller, casually telling it to all they meet.

Well, pretty soon a “distinguished speaker” delivers the commencement address. Next, the college president asks that during the awarding of diplomas, alphabetically for efficiency’s sake, all applause should be withheld until the end.

But I’ve never seen these diploma awardings reach the C’s before some Grandma, unable to contain herself, rears upright, head thrown back, emotionally shouting, “Thank you, Jesus!” Thereafter, the small Black college commencement resounds like a camp meetin’.

To me, another prime example of Black family strength is what I see on Sunday mornings as I travel extensively. I see the Black congregations, the living generations, filing to and from their houses of worship. They are such graphic reminders of that brilliant observation, “The family that prays together stays together.”

Another favored statement of mine is “Either you deal with what is the reality, or you be sure that the reality is going to deal with you.” Yet another favorite: “If you think education is expensive, then try ignorance.”

I know of nowhere that both apply more than among both young or older Black people who elect to ignore the richness of our ethnic heritage. Those long gone, as well as our living Black elders’ strength, courage and resilience—which tend to dwarf our own—enable our having our opportunities, such as they never even remotely knew. ~ Alex Haley.

(We Must Honor Our Ancestors by Alex Haley is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the August 1986 issue of EBONY Magazine. © 1986, 1990, 1993 EBONY Magazine. All Rights Reserved.)