(Alex Haley granted the following interview to Orient writer Doug Hatcher before his lecture in Pickard Theater October 5, 1984.)

(Alex Haley granted the following interview to Orient writer Doug Hatcher before his lecture in Pickard Theater October 5, 1984.)

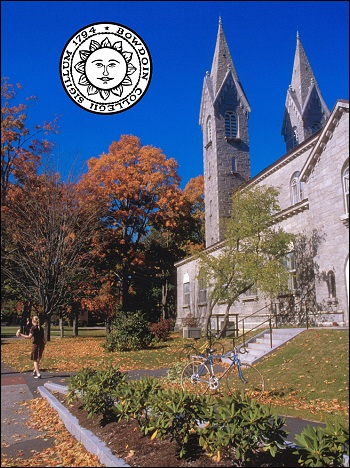

Tonight, Bowdoin’s impressive series of fall lectures continues as Alex Haley speaks at 8:00 p.m. in Pickard Theatre. His presentation is entitled “The Family: Find the Good and Praise It,” and it is open to the entire Bowdoin community.

Author of Roots, the biggest bestseller in U.S. publishing history, Mr. Haley is also the recipient of America’s two topmost writing awards, the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In addition, the film version of Roots drew the greatest television audience in history, over 130 million viewers, when it was run over seven consecutive nights in January of 1977.

In 1952, Haley was named chief journalist, assisting the handling of U.S. Coast Guard public relations in addition to composing his own manuscripts. He retired in 1959 after 20 military years and ventured into a new career of full-time freelance magazine writing.

His first book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, was published in 1965 and was selected among the ten best books of the 1960s. It is now required reading in most U.S. high schools and colleges. Haley’s second book, Roots, which traces some 200 years and six generations of the maternal side of his family, is now published in 37 translations and has sold over six million copies. Time magazine has labeled Haley “a folk hero,” and his book Roots, “a cultural landmark.” He has been awarded seventeen honorary degrees.

The lecture is sponsored by the Student Union Committee, the Dean of Students office, the Afro-American Society, the History department, the Lectures and Concerts Committee, and the Golz Lectureship.

A Talk With Haley

Orient: You have a new book coming out, isn’t that right?

Haley: Yes, it’s called Henning. It’s the name of my hometown, and it won’t be out until the end of next year.

Orient: Is it fictional or a little bit non-fictional?

Haley: It’s nostalgia—stories about people and events in that little town when I was a little boy growing up there. It’s true stories about the way things were.

Orient: I’ve heard that there’s a possibility of your doing something on the topic of China? What exactly does this new project entail?

Haley: It’s going to be a television show—like a mini-series—kind of based upon, adapted, from the history of China since 1900.

Orient: What prompted you to do this?

Haley: Interest. I like to do new things.

Orient: The lecture topic tonight is on the family. What kind of family-related things are you going to bring in.

Haley: Actually, I talk about writing—how I got to be a writer. It’s kind of an evolution thing of how one thing led into another. Now I’m regarded as somebody who knows a great deal about the family. The fact is I am imaged with knowing more than I really do know. But, it’s a subject that people like to talk about, and I discuss it in context with things that I’ve learned or things that have come to me with regard to the family since Roots came out.

Orient: You’ve just jumped to something that is really the major part of what I want to ask you about: that is, your writing career. How much of an impact did Malcolm X have on your career in terms of his being not only a vehicle for furthering your career but also an impetus behind a new phase of writing for you?

Haley: It had a big, big impact in the sense that it moved me from magazine articles to world of books. It marked a transition for my career.

Orient: I know you’re biased in terms of Malcolm X in the sense that you helped in writing his autobiography, but I am interested in your view of Malcolm X as compared to Dr. King.

Haley: Well, I’m not necessarily biased, at least I don’t think I am. They were two people with fundamentally the same objectives who simply went about it differently. They had different perspectives. One of the things that kind of intrigues me is to reflect upon how easily either man might have been the other, given the other’s background. Had Dr. King grown up in the ghetto of Roxbury, in Massachusetts, and moved from there to Harlem’s ghetto, he might have been exactly as slick as Malcolm—you know, a hustler, in the world of neo-crime and what not just as quickly as Malcolm. Many, many people who are as brilliant as Dr. King are in penitentiaries today. I speak at a number of penitentiaries, and one thing that always strikes me is to realize that I am looking in the same intelligent faces I see in universities—they just happen to be in prison. And I know that Dr. King might have done that just as easily as had a Malcolm X—or a Malcolm Little as his name was—had he had the opportunity to grow up in a good high school, to go to Boston University, to study theology . . . think what a minister he would have been given his natural talent as a speaker. So it’s just a question of “there but for the grace of God” in either direction. That’s the way I see it, and to me that’s the intrigue of them; they were really so much alike—they just happened to be of different perspectives.

Orient: Do you believe that Malcolm X was becoming less militant just prior to his assassination?

Haley: To a certain extent I think he was. He was coming about almost full circle, and yet I wouldn’t say he was becoming necessarily all-that-much less militant as he was changing his perspective about the same thing. By that reasoning one could say that Dr. King was generally pictured as less militant. As a matter of fact there’s a question as to which one did more. Another one of the ironies is that Dr. King, who was imaged with less militancy, as well as peace and peacefulness, was the one who was physically pushed around, who was jailed time and time again, and Malcolm X, who was imaged with violence, never spent a day in jail in that area … He never had to do with perspective ought to be something like that of a surgeon with a patient on the operating table because you are there to do some surgery, and the best you can do is go do it and not get caught up emotionally. And it’s true you ought to be able to look at your subject with a certain degree of objectivity so that you can write somewhat objectively about them.

Orient: This idea of objectivity is very evident in your epilogue (in the autobiography) where you’re talking about his being murdered. Your style is very journalistic.

Haley: Well that’s what it was—it was very plain that sooner or later he was going to be murdered. So you just deal with that—that’s the way it is.

Orient: In Ossie Davis’ essay eulogizing Malcolm, Davis says that Malcolm X was the manhood for black people, implying that he was someone to whom blacks looked—a sort of role-model. Who are black role models today for black people, or even white people.

Haley: There are a great many more today than there were at that time. You know one thing I like I think about them was that the then-President Kennedy one time called five black men together at kinds of elected officials all over the country and into the South. So you can’t really anymore say that there are a few black leaders, it’s just not true. There tends to be now more of a local or regional leader. There are a few who have a national stand like Rev. Jesse Jackson, but I wouldn’t say that he was the Holy Grail for black people. He’s there, but he’s one among.

Orient: Do you consider yourself a black role-model?

Haley: I would say I probably am a role-model for a great many people, simply because I do something that many people know about, and lots of young black people want to write. I guess if I didn’t consider myself in this way I would ignore my mail—that’s the biggest place I get that image of myself.

(The above interview of Alex Haley by Doug Hatcher is presented under the Creative Commons License. It was originally published in the October 12, 1984 issue of The Bowdoin Orient. © 1984 The Bowdoin Orient. All Rights Reserved.)